Dying Rose: Teen’s sudden death and haunting final texts spark a search for answers – and expose an alarming pattern

Rose was a 19-year-old, bright, bubbly, lover of the arts and a budding model. Does a bloodstained phone’s haunting final messages hold the key to her sudden death?

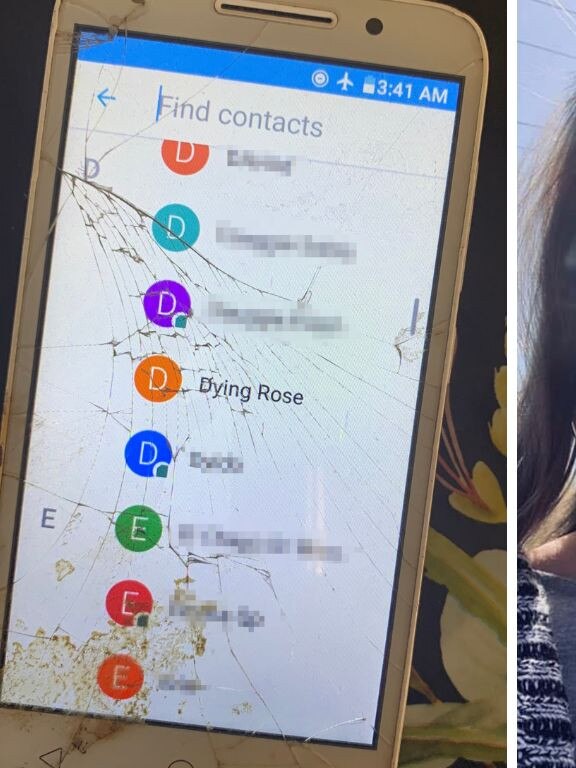

Dying Rose

Don't miss out on the headlines from Dying Rose. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It has been 1354 days since Courtney Hunter-Hebberman’s daughter, Rose, was found dead in a shed at the back of a unit block in Adelaide’s south.

Within hours, the 19-year-old’s death had been ruled a suicide. Messages found on Rose’s blood-smeared phone, kept by police for nearly three years, held a harrowing glimpse into her final moments.

But her mother’s unanswered questions about the circumstances in which she died sparked a relentless pursuit of answers – and shed light on a national shame.

Rose is one of six Aboriginal women whose cases are being investigated by The Advertiser in Dying Rose, a podcast in which their families ask whether police properly responded to their deaths.

It was December 4, 2019, when Courtney opened her door to the unthinkable.

Police told her that her daughter, Rose Hunter-Hebberman, had taken her own life by hanging at the home of Jared (a pseudonym), a man she had met earlier that year.

“The officer’s just shaking his head, he was crying. He’s like, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry’ … I just felt like, my body was like, twisting sideways,” Courtney said.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this story contains images and voices of people who have died.

DYING ROSE: LISTEN TO EPISODES 1 & 2

PODCAST: Listen to the first two episodes here, or find them on the Apple Podcasts app

Described by those who knew her as bright, bubbly and fiercely independent, Rose was a passionate supporter of the arts and had just been offered modelling work.

Peramangk and Ngarrindjeri woman Courtney said she had been concerned about her daughter's relationship with Jared in the months leading up to her death.

“He owed thousands and thousands of dollars in debt ... she had tried to help him essentially get his life together,” she said.

A neighbour who lived at the block of housing trust units where Rose died said she had heard aggressive arguments between the pair.

Courtney said Rose’s mental health had been declining and at times she had walked out of Jared’s home but didn’t want to leave her dog, Phoenix, behind.

In the days that followed Rose’s death, Courtney began to question why it had been ruled a suicide at such an early stage.

She said Rose had been planning on leaving Jared’s house the day she died.

“At that stage (police are) trying to say it’s not suspicious, but I’m thinking ‘how is it not suspicious?’,” Courtney said.

“She wanted to leave. She didn’t message any of us to say ‘I’m gonna kill myself’ … then all of a sudden she’s just dead on the floor of the shed?”

She asked police to provide evidence supporting their conclusion that Rose had taken her own life, including CCTV footage of Jared’s whereabouts on the morning she died. An autopsy report on Rose’s death said he was at work.

But she said they never searched for the footage. SA Police declined to comment on that or any other assertion made by the family, and referred inquiries to the coroner.

The Coroner’s Court refused a request for access to documents related to the case because it was not heard at inquest.

The Advertiser has made multiple attempts to contact Jared but has not received a response. There is no evidence he played a part in Rose’s death, which the autopsy concluded was a suicide.

The autopsy also said that police could not initially pinpoint the exact location where she had been hanging before she fell into a seated position against the couch.

Courtney raised concerns that police had not interviewed potential witnesses, including neighbours and Rose’s best friend, Casey, who was living at the house at the time.

The mystery of ‘Dying Rose’

Courtney was studying a law degree before her daughter died and, in the belief that police had not investigated properly, made her own inquiries.

Using her knowledge, she began collecting evidence – and even kept the bloodstained couch her daughter had been found on in the hope it would eventually provide answers.

“Police didn’t listen to us from the beginning. They said I was just being emotional. Of course I’m emotional – but at the same time, there was doubt that needed to be investigated,” Courtney said.

“I sent them an email outlining all the different points of evidence that I thought that we had and asked for the investigation to be pushed further … not once did they say they were going to look at it.”

In her investigation, Courtney discovered a phone inside Jared’s house.

On that phone, she found notes she believes were written by Jared, appearing to be rap lyrics with alarming phrases such as: “I’m a f****** violent person, earning and burning”.

There was also a contact on that phone listed as “Dying Rose” – but the number has since been disconnected, making it impossible to determine who it belonged to.

Police held Rose’s belongings in evidence for years, with her phone and other personal effects only returned to Courtney in October 2022.

“Three years of not being able to view any of that stuff relating to a deceased family member,” Courtney said.

“It’s not a priority (for police), especially if it’s a young Aboriginal woman. Even if it is a suicide, the trauma that’s created to victims all over again by the lengthy process by not being able to view evidence … it’s ridiculous.”

On her phone, Courtney discovered more than 500 text messages and 45 phone calls exchanged between Rose and Jared on the morning of the day she died.

In those, Rose made clear that she intended to harm herself.

At one point, Jared offered to call an ambulance – but stopped responding a short time later. Her final harrowing text messages went unanswered.

“You’re not even answering. Maybe I should just die then,” she wrote.

When he eventually did respond hours later, his first words were: “If my money or Phoenix isn’t there, I will be reporting you to the police.”

A national shame

Courtney’s quest for answers led The Advertiser to the stories of five other Aboriginal women across the country – Charlene Warrior, Lasonya Dutton, Lyla Nettle, Shanarra Bright Campbell and Charli Powell – whose deaths told a shockingly similar story.

All of their families had unanswered questions about how their loved ones died or the police response to their deaths.

Courtney believes the issue is systemic, and leading to devastating outcomes.

“There will never be any justice for my daughter, but this is happening for everyday Aboriginal families because of the racial bias that exists within the system,” she said.

WA Senator Dorinda Cox, a Yamatji–Noongar woman, said Courtney’s story echoed a national crisis, as Australia’s policing and justice systems fail to hear the voices of First Nations families.

After a successful motion in 2021, Senator Cox is now fronting a landmark senate inquiry examining the “unacceptable” rates of missing and murdered First Nations women and children.

“Our communities feel angry, they feel frustrated, they feel hurt – and most of all, they feel helpless,” Senator Cox said.

“There is often a justification (for the police response) that is not the same as if it was a non-Indigenous woman, because of their history or because police may have had a separate interactions or incidences that have involved that woman.

“That should become irrelevant and we should be prioritising their safety.”

DYING ROSE PODCAST: Listen to the first two episodes here, or find them on the Apple Podcasts app

REACH OUT FOR HELP

While the media generally avoids reporting details about suicide, to understand the families’ concerns about these cases it is important to give the full context of these tragic deaths.

• Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders requiring crisis support can call 13YARN (13 92 76)

• Anyone needing help with issues of mental health or depression can call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636

• If you or someone you know is experiencing sexual abuse or family violence, call 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732)

• Men experiencing anger or relationship issues can call Men’s Referral Service on 1300 766 491

• In an emergency, call 000

More Coverage

Originally published as Dying Rose: Teen’s sudden death and haunting final texts spark a search for answers – and expose an alarming pattern