Melbourne terror plot: How Ezzit and Ahmed Raad were radicalised

EZZIT and Ahmed Raad grew up in a stable, happy house in Brunswick where they wanted for nothing and had drifted away from the Islamic religion. Which is why the leap from docile Melbourne schoolboys to homegrown terrorists was so frightening.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS the shrapnel tore through Ezzit Raad’s chest, he had become the fourth in his family to die in the name of terror.

And what is frightening is that the leap from docile schoolboy to homegrown terrorist was so quick.

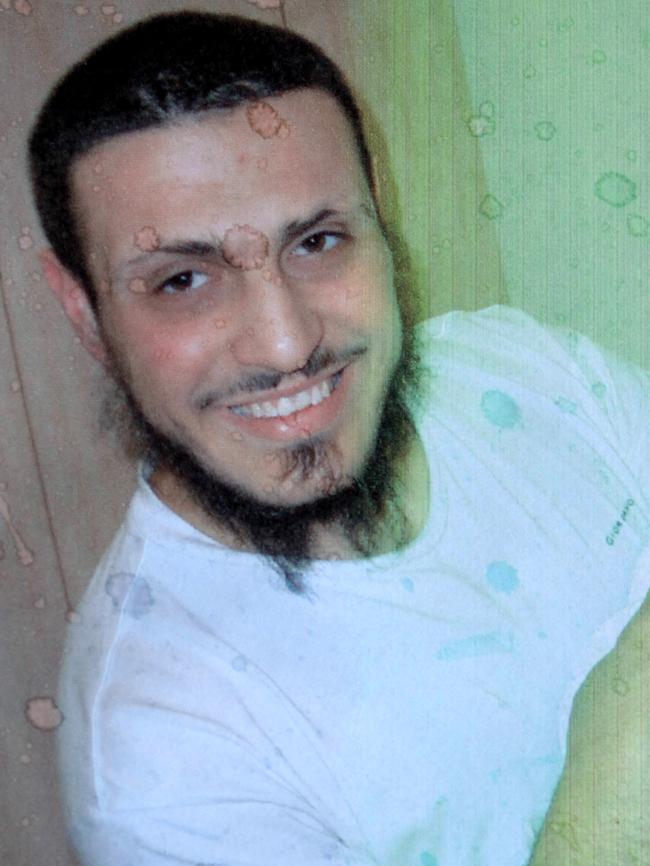

Two years ago a story appeared in ISIS propaganda magazine Rumiyah — a picture capturing Ezzit’s motionless face, the at-rest image broken by blood on his forehead.

It was, in fact, an image of his corpse.

He had died just 12 years after being radicalised by firebrand Muslim cleric Abdul Nacer Benbrika.

But he did not die alone.

Ezzit was the son of Lebanese immigrants, who Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser gave refuge.

They fled civil-war strife during the mid-1970s to build a better life in Australia.

Like many, they would settle in Brunswick, near Sydney Rd, a melting-pot for immigrants.

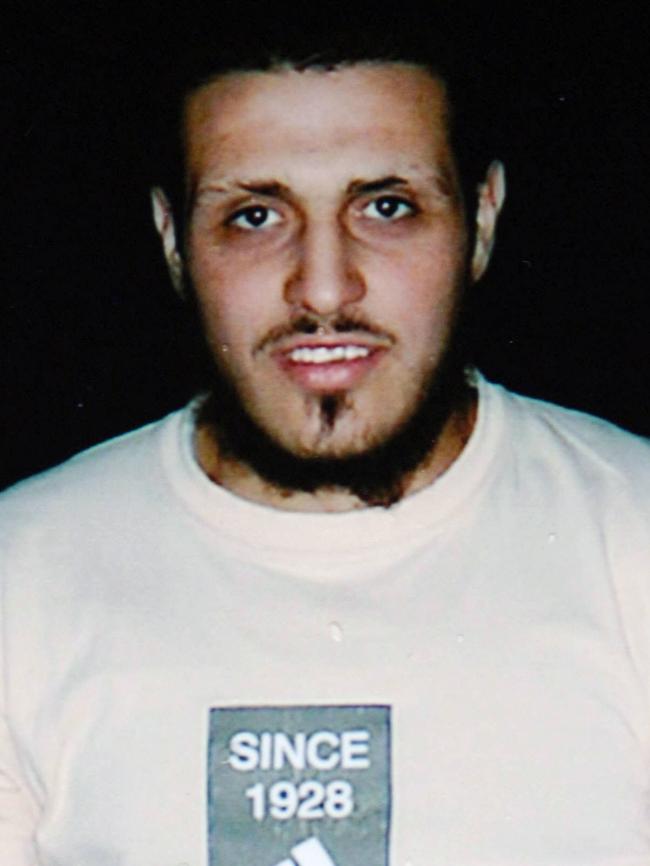

Ezzit, born in 1981, wasn’t born in a war zone.

He was the third of the Raad sons, a brood of eight boys from Brunswick.

His younger brother Ahmed came a year later.

They grew up in a stable, happy house and despite it being cramped and the finances stretched, they wanted for nothing.

During their formative years, they could be wild. Both Ezzit and Ahmed had drifted away from the Islamic religion.

In what Ahmed would state in his police interview “the bad life’’, “which is, uh, sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll.’’

He was asked by officer Tony Wheatfill what made him become religious. The answer: “Uh — my brother passed away.’’

The brothers, neither academically gifted, left school in 1999 for careers.

Ezzit, who completed his VCE, would take up an electrician’s apprenticeship. Ahmed would try his hand at spray painting, only to develop skin irritations to the chemicals, before an injury ended a short-lived plumbing apprenticeship.

It was followed by telemarketing and a failed online business supplemented by WorkCover payments.

In 2003, their would be a religious calling.

The effect of an older brother, Mansour, dying suddenly of a coronary disease struck hard.

And it led them to the mosque.

They sought out different teachers, eventually falling under the guidance of Benbrika and the path towards Jihad was underway.

The brothers were joined by their younger sibling, Majed, and cousin Basam, who like them would come under Benbrika’s spell.

Benbrika was building cells in Melbourne and Sydney, and preparing to punish the nonbelievers for Australia’s role in Iraq.

“We will damage buildings. Blast things,’’ terror cell leader Benbrika was secretly recorded saying.

“Everyone has to prepare himself. If we want to die for jihad, we have to do maximum damage, maximum damage.’’

The journey from apprentice tradie to terror plotter took less than two years.

BENBRIKA’S TERROR CELL

The steps towards jihad would be tentative for the Raads, but they drew inspiration from al-Qaida.

But from early 2004 until AFP — VicPol dawn raids, Abdul Nacer Benbrika’s plans would become clearer as he brainwashed his members.

Ezzit, Ahmed, Majed and Basam were being motivated by a belief that the world Islamic community was under attack from non-Islamic forces.

They were to engage in violent Jihad to protect Islam from its enemies — the kafir (infidel nonbeliever) — including the Australian Government which the group believed should withdraw its troops from Iraq and Afghanistan.

To finance its Jihad, the group needed money.

A Sandooq (Arabic for a money box) was under Ahmed’s control.

Ezzit, to help raise cash, committed his first serious crime. He stole a car.

The brothers, on September 10, 2004, held one of only 23 conversations in which Ezzit would be intercepted in a massive bugging operation.

The bug was hidden in Ezzit’s garage but he is unsure about his actions. Ahmed reassures him:

“They’re kafir man, stuff them man, they’re killing our brothers and sisters and little kids.’’

They would become embroiled in a car-rebirthing racket, credit-card fraud and other illegal activities.

More than $18,000 was raised in the Sandooq and used by the group to fund their activities, including a court imposed fine for Ezzit’s illegal activities.

They were also associating with a more advanced terror cell under Benbrika’s control in New South Wales, which had acquired bomb building chemicals and weapons.

In December, 2004, Ahmed would travel with his old school friend and joint terror plotter Fadal Sayadi to Sydney, where they met with Khaled Sharrouf and Abdul Hasan.

On April 30, 2005, police detected Ezzit talking to his younger brother Majed and Benbrika about “killing police officers in pursuit of jihad”, a court heard.

By July, 2005, Benbrika was advocating for terror, telling Ezzit and Majed six days after the London bombings that al-Qaida was behind it.

The Raads by now were attending training camps and were associating with Shane Kent — a man who it would be alleged met and swore allegiance to Osama bin Laden.

By then, they had been infiltrated by an undercover police operative.

Although some didn’t trust him, Benbrika did.

On November 8, 2005, police swooped in Melbourne and Sydney, arresting the key members of the terror cell, including Ezzit and Ahmed.

For Ahmed was caught red-handed.

A document titled “The Nineteen Lions’’, which glorifies the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Centre and Pentagon, was among the al Qaida propaganda in his possession.

Other material seized had been discussed by Ahmed, including the Islamic ruling on killing women and children in Jihad.

All but three of Benbrika’s terror cell refused to comment during their police interview. But Ahmed and Ezzit did.

Ahmed denied swearing a pledge to Benbrika, known as “bayut’’.

But although he said he could not kill innocents, violent Jihad to protect his religion was defensible.

“Yeah, nothing wrong with that,” he said.

“As long as you do it properly.’’

Ezzit, who was only recorded in 23 conversations, and Ahmed would be convicted of belonging to and funding a terrorist organisation.

Majed and cousin Basam would be acquitted.

By 2012 both Ezzit and Ahmed were free men.

Although their jail terms had not been crushing, they spent most of their time in maximum security incarceration holed up with gangland killers.

The deradicalisation programs did not work on them.

Ezzit, in particular, walked out of prison with a deeper hatred. Both believed they had been wrongly convicted for “talk’’ expressing their religious beliefs.

Former counter-terrorism investigator Peter Moroney, who has recently released a book titled Terrorism in Australia, said any argument from the Raads that they were exercising “free speech’’ was erroneous.

“Police aren’t in the habit for prosecuting people for freedom of speech,’’ Mr Moroney said.

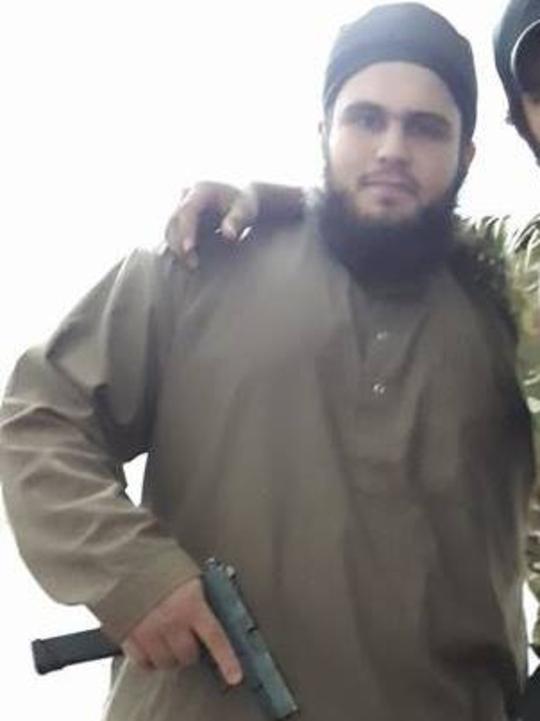

Ezzit, however, breached security by using a relative’s passport to fight for Islamic State in Syria.

He said Ezzit Raad’s ability to breach Australia’s border controls would have been probed and that no system was fail safe.

“I would expect that at a minimum an investigation would have most certainly been done,’’ he said.

“I don’t know if one was, but given the circumstances it would have had to have been.

“The level of control at the airport is only one aspect and shouldn’t be isolated when the security is reliant upon a combined effort from law enforcement, security and intelligence agencies well before a person arrives at customs.

“It would be difficult to isolate the issue with the borders. I know a great deal as been done since, but not entirely sure that we will ever be fail safe.’’

RECRUITING FOR ISIS

WITHIN months of gaining his freedom, Ezzit Raad had used a relative’s passport to flee Australia and join Islamic State.

Ezzit, in 2013, left behind his wife and four children.

He would be dead three years later, killed in the city of Manbij after being struck with shrapnel.

He died having already recruited two of his brothers and extended family to Islamic State’s killing fields.

Younger Raad brothers Majed and Mounir, his nephew, Zakariyya, along with Ahmed’s brother-in-law, Adam Dahman are presumed, or in fact, dead.

Dahman, in July, 2014 aged just 18, strapped a belt-bomb to his waste, walked into a crowded area outside a Shiite mosque and detonated it.

Ezzit died in 2016. Islamic State used his death as a call to Muslims for killing in the suburbs of Melbourne and Sydney.

“Kill them on the streets of Brunswick, Broadmeadows, Bankstown and Bondi,’’ Islamic State propaganda magazine Rumiyah declared.

“Kill them at the MCG, the SCG, the Opera House, and even in their backyards.’’

Predictably, Raad’s death fighting for the terrorist cult was glorified.

An image of his face, post death, was published and his “martyrdom’’ came when his “blood was spilled’’, according to the magazine.

Ezzit’s traits, such as convincing younger, vulnerable relatives to follow him to Syria was overlooked.

It described Ezzit, known as Abu Mansur, as having been born in Lebanon before growing up in Melbourne, Australia: “a land cloaked in darkness and corrupted by kafir (non-believer).’’

He was even quoted about his disappointment at not dying before his nephew, Zakariyya

“He achieved it before me,’’ Ezzit is quoted as saying.

“He was more truthful than me.’’

Ezzit, it said, became among the first to enter the “blessed land of epic battles’’ and became one Islamic State propaganda merchant’s Bakr al-Iraqi’s closest companions.

He also took a second wife.

“Abu Mansur, however, was not one to make concessions to the kuffar at the expense of his religion. This angered the Australian government forcing them to plot against the muhawiddin with new, retrospective anti-terrorism laws that allowed them to prosecute and imprison Mansur for being part of a terrorist organisation.’’

It cites Victorian Iman Mohammad Omran as a traitor against the homegrown terror plotters. It argues that the “abuse’’ of women by the nonbeliever, inclusive of moderate Muslims, as being “abused, vilified, imprisoned and violated.

“This was one of the things that burned at Abu Mansur the most, for he had tremendous jealousy for his sisters and his eyes would well with tears every time he heard of their suffering.’’

But it lauded Ezzit’s decision to leave his family in Melbourne to fight for ISIS, and marry a second wife with whom he had a child.

Among his “achievements’’ was to draw closer to his god during his five years in prison, it said.

“Abu Mansur was released from prison more emboldened and more steadfast upon this path.

“He quickly set out to make hijrah (his journey), leaving behind his beloved wife and four children in order to bring triumph to this religion and to quench his thirst for the blood of the Nusayriyyah (non-believers).’’

Ezzit Raad’s former barrister, Greg Barns, believes Ezzit’s radicalisation was strengthened in maximum security prison.

And he said questions must be raised as to whether or not his prison experience can be linked to his travelling to Syria to join IS.

“The experience of Ezzit Raad should have politicians and prison authorities questioning whether treating convicted terrorists in a harsh prison environment is in fact making them more dangerous on release,’’ he said.

It is too late now.

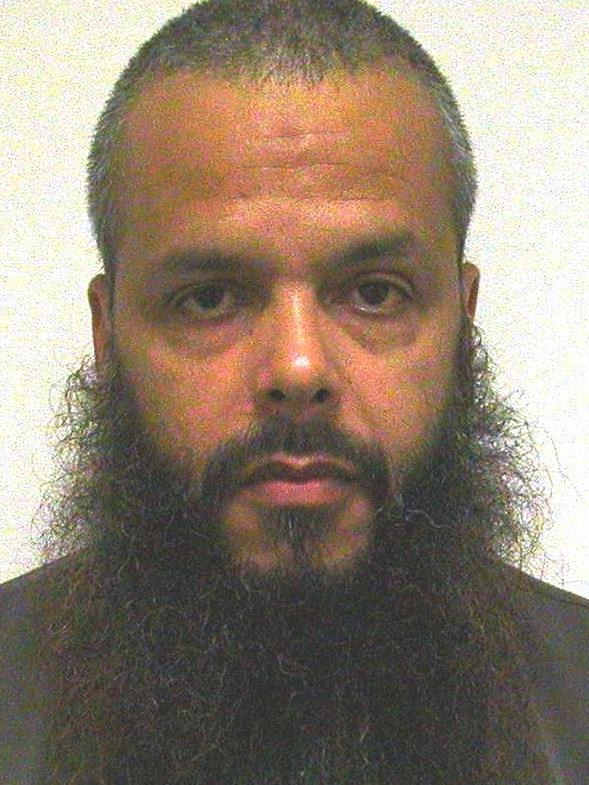

Ahmed, a convicted terrorist who went on training camps in the NSW bush with Benbrika, has, according to his wife, Maryanne, left that life behind.

But she said Ahmed still believes he was wrongly convicted and not a danger to anyone.

She said they were not longer “affiliated’’ with other members of the family who had radicalised or broken the law.

“A lot of people have sad stories in life,’’ she said.

“We have moved on. What’s done is done. We do everything right. We pay our taxes.

“If he (Ahmed) was dangerous he would not be out on the street.

“It’s my life and it’s all in the past,’’ she said.

Only one Raad connected to the family is currently inside a Victorian prison, and it is not for a terrorism offence.