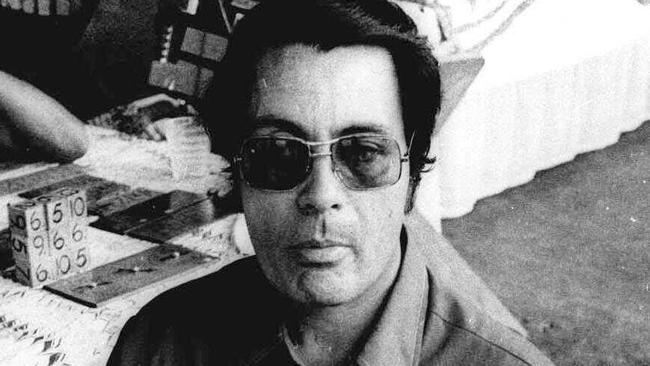

Jonestown Massacre survivors revisit Jim Jones’ atrocities 40 years on

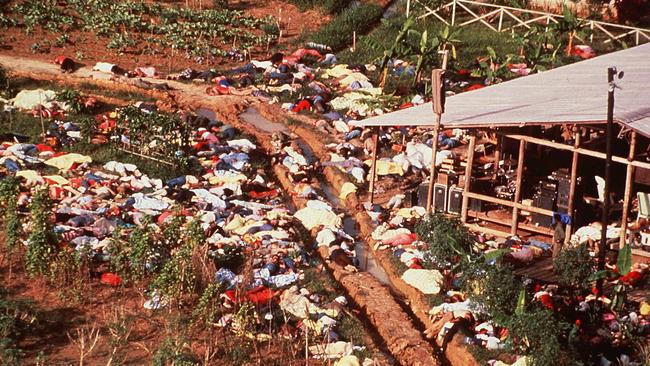

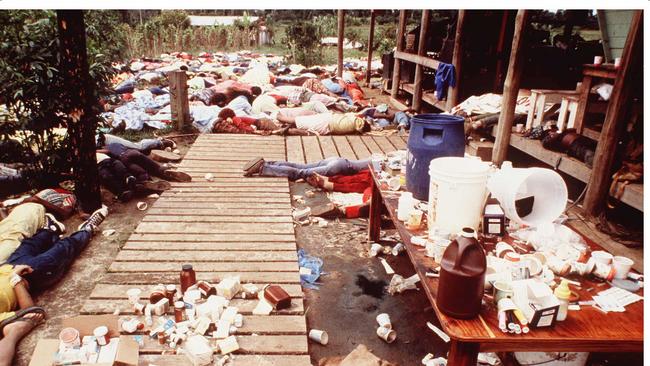

Forty years ago, more than 900 people died in the mass murder-suicides in Jonestown, orchestrated by cult leader Jim Jones. Now, survivors have returned to the site to speak about the atrocity - and how they escaped.

WARNING GRAPHIC CONTENT AND IMAGES:

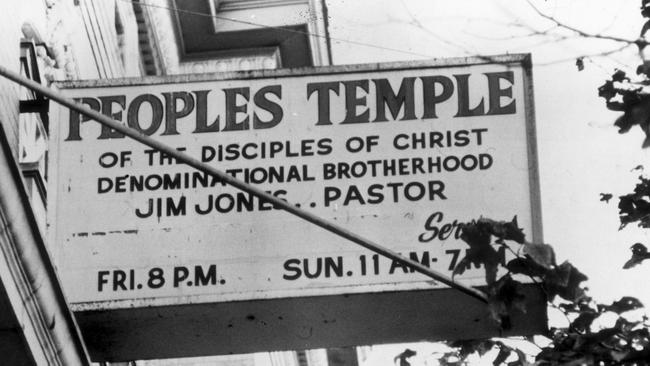

Forty years ago this week, a California congressman and a group of journalists travelled to South America to see Jonestown, a remote settlement created by an American church, and investigate reports of abuses of members.

As the visitors prepared to return to the US, Peoples Temple gunmen ambushed them on a jungle airstrip, killing the congressman, Leo Ryan; three newsmen; and a church defector.

The shooting triggered the mass murders and suicides in Jonestown of more than 900 people orchestrated by the Reverend Jim Jones.

This week ceremonies at a California cemetery marked the mass murders and suicides.

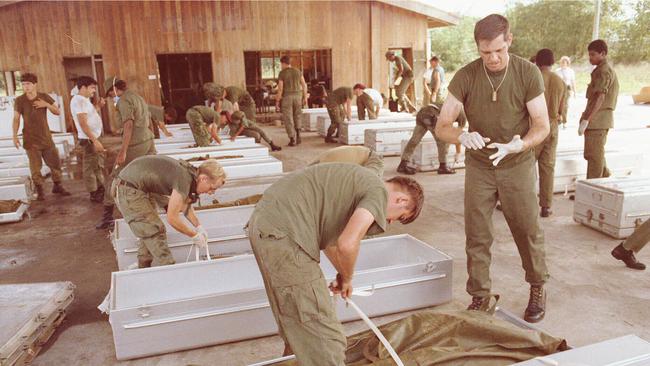

The remains of more than 400 Jonestown victims are buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland.

Jones’ adopted son Jim Jones Junior and other former Peoples Temple members conducted a service on Sunday (local time) at granite slabs bearing the names of all 918 who died in Guyana on November 18, 1978.

Minister Jynona Norwood, who lost 27 relatives, separately unveiled a portable memorial wall to honour more than 300 children and other victims. She left off the names of Jones and those she says assisted him.

JONESTOWN: THE SURVIVORS

Jonestown was the highlight of Mike Touchette’s life — for a time.

The 21-year-old Indiana native felt pride pioneering in the distant jungle of Guyana, South America.

As a self-taught bulldozer operator, he worked alongside other Peoples Temple members in the humid heat, his blade carving roads and sites for wooden buildings with metal roofs. More than 900 people lived in the agricultural mission, with its dining pavilion, tidy cottages, school, medical facilities and rows of crops.

“We built a community out of nothing in four years,” recalled Touchette, now a 65-year-old grandfather who has worked for a Miami hydraulics company for nearly 30 years.

“Being in Jonestown before Jim got there was the best thing in my life.”

At 16, Jordan Vilchez was put on the Planning Commission where the meetings were a strange mix of church business, sex talk — and adulation for Jones.

“What we were calling the cause really was Jim,” she said.

Instead of finishing high school, Ms Vilchez moved to San Francisco, where she lived in the church. Then, after a 1977 New West magazine expose of temple disciplinary beatings and other abuses, she was sent to Jonestown.

Gruelling field work was not to her liking. Neither were the White Nights where everyone stayed up, armed with machetes to fight enemies who never arrived. Ms Vilchez was dispatched to the Guyanese capital of Georgetown to raise money. On November 18 she was at the temple house when a fanatical Jones aide received a dire radio message from Jonestown. The murders and suicides were unfolding, 150 miles away. They must kill themselves.

Within minutes, the aide and her three children lay dead in a bloody bathroom, their throats slit.

For years, Ms Vilchez was ashamed of the part she played in an idealistic group that imploded so terribly. “Everyone participated in it and because of that, it went as far as it did,” Ms Vilchez said. She’s now an artist who had worked for 20 years in a private crime lab.

This past year, she returned to long-overgrown Jonestown. She could only sense the site of the pavilion, the once-vibrant centre of Jonestown life where so many died — including her two sisters and two nephews.

“When I left at 21, I left a part of myself there,” she said.

“I was going back to retrieve that young person and also to say goodbye.”

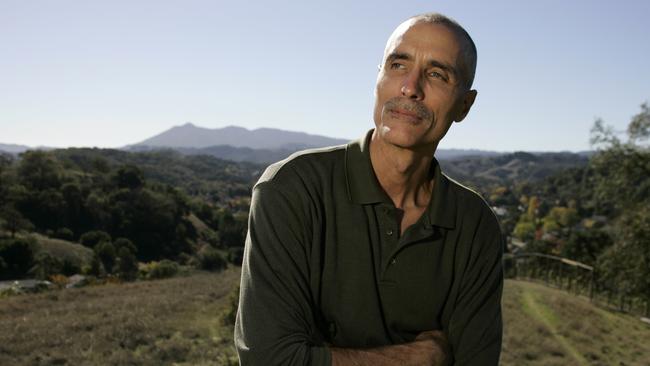

Though he waved and smiled at Peoples Temple services, seemingly enraptured like the rest, Stephan Gandhi Jones said he always had his doubts.

But Stephan was the biological son of Jim and Marceline Jones. And the temple was his life — first in Indiana, later in California.

As a San Francisco high school student, he was dispatched to help build Jonestown.

Stephan helped erect a basketball court and form a team. In the days before Ryan’s fact-finding mission to the settlement, the players were in Georgetown for a tournament with the Guyana national teams.

Rebelling, they refused Jones’ order to come back, believing nothing would happen or he was too cowardly to follow through with the oft-threatened “revolutionary suicide.”

Stephan Jones and some other team members believe they might have changed history if they were there.

“The reality was we were folks who could be counted on to stand up,” he said.

“There is no way we would be shooting at the airstrip. That’s what triggered it.”

He went through years of nightmares, mourning and shame. To cope, he says he abused drugs and exercised obsessively.

“I focused my rage on dad and his circle, rather than deal with me,” he said.

More than 300 Jonestown victims were children. Now, Stephan Jones is father of three daughters, ages 16, 25 and 29, and works in the office furniture installation business.

He says his daughters have seen him gnash his teeth when he talks about his father, but they also have heard him speak lovingly of the man who taught him compassion and other virtues.

“People ask, ‘How can you ever be proud of your father?”’ he said. “I just have to love him and forgive him.”

Jim Jones’ adopted son, Jim Jr., also was with the basketball team at the time of the massacre. He says he tried to persuade his father not to go ahead with his murderous plan: “I said there must be another way.”

Jim Jr. would lose 15 immediate relatives in Jonestown, including his pregnant wife, Yvette Muldrow.

He would build a new life. He remarried three decades ago, and he and his wife Erin raised three sons. He converted to Catholicism and registered Republican. He built a long career in health care, while weathering his own serious health problems.

He took a lead role in the Jonestown memorial at the Evergreen Cemetery.

EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF MASSACRE

Then-San Francisco Examiner reporter Tim Reiterman was wounded in the airstrip shooting and flown to Andrews air force Base in Maryland, where he wrote the following eyewitness account. It appeared in the Examiner on Nov. 20, 1978, two days after the tragedy:

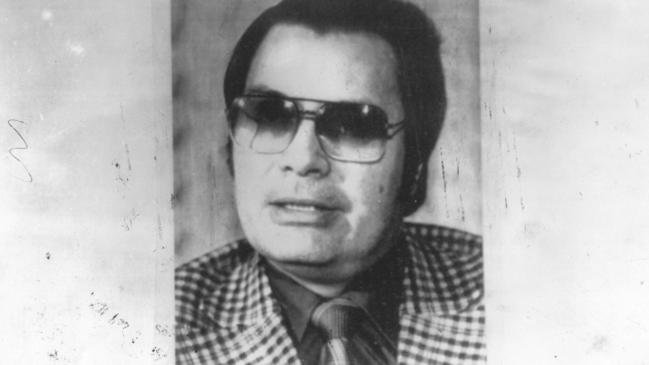

“I feel sorry that we are being destroyed from within,” the Rev. Jim Jones had said as a tropical storm rained on the Peoples Temple pavilion.

Jones had suffered a setback. Rep. Leo Ryan, D-San Mateo, had come to the temple’s agricultural project to determine whether the followers of Jones were free to leave the jungle settlement. And now some wanted to depart. We couldn’t know then that the grim little world of this sick man would shatter within hours, taking hundreds of his followers to their deaths. My companion, Examiner photographer Greg Robinson, would be murdered in an ambush. So would the congressman and three others.

I wondered why it happened. My best guess is that Jones felt the press people weren’t fooled by the staged set up at the mission. After all, we had seen things we weren’t supposed to see. We demanded to see the locked buildings where some members lived in crowded, uncomfortable conditions.

Jones wasn’t the same man. His handshake was weak. He was taking pain pills, and he said he was dying.

None of it makes sense. All I can do is tell what I saw and heard. It began with a note smuggled to us from two members. The note said: “Please help us get out of Jonestown.” The list of defectors rapidly grew to at least 16. According to former members, Jones would not tolerate defections from the mission project and many of the church members considered those who leave to be traitors.

At the end of Ryan’s two-day visit to the mission Saturday, a woman suddenly charged down a slippery boardwalk shouting at her husband, “I’ll kill you! I’ll kill you! Don’t take my baby!” An emotional tug of war ensued between a mother who wanted to stay and the father who wanted to go. Finally, attorneys for both Ryan and the temple decreed that the courtroom was the proper place to decide the custody issue. Though it was a stalemate, the incident intensified an already strained situation. Jones, who asked his followers to call him “Dad,” did not like to lose any of his “children.” He said he considered it a failing on his part when he did.

Some scowling faces appeared in the windows that rainy afternoon, watching the defectors leave, some with trunks and others with little more than the clothes on their backs.

All of us were falling and slipping through the mud around a six-wheel-drive dump truck that would take us (the congressional delegation, the press, the defectors and a group of concerned relatives of temple members) to the Port Kaituma airstrip.

In minutes, the back of the truck was piled high with crates, suitcases, backpacks and people. Mud made the truck bed slick, so everyone clung to the sideboards.

“Let’s go!” someone shouted, and the driver attempted to turn the truck around. The truck spun its wheels until a Caterpillar tractor tugged it into place for a downhill run.

But before we could start out, we heard angry shouts. People raced over to the outdoor pavilion.

A few of us jumped from the truck and ran over there. We got word that a temple member had grabbed the congressman, held a knife to his throat and told him he was going to slit it. Temple attorneys Charles Garry and Mark Lane, along with Ryan, subdued the man.

We were turned back by Johnny Jones, Jim Jones’ stern-faced adopted black son. He said reporters would make the situation worse.

A few minutes later a pale-looking Leo Ryan slogged through the mud with his briefcase, his powder blue shirt and pants stained with his assailant’s blood. He climbed aboard the truck and we took off.

Ryan had planned to remain behind at the mission with several members who wished to return to the United States but couldn’t get seating on the planes. His unplanned departure left them alone.

“They’re in deep trouble now,” observed one of the relatives who had accompanied us.

During the bouncy ride out, former temple members said that one of the supposed defectors, Larry Layton, was a Jones loyalist and had been depressed. “Watch him,” those around him were told. “We think he’s got a gun. He’s too close to Jim Jones to leave.” A large poncho covered his belt area so no one knew for sure and no one challenged him.

“I’m real happy to be getting out,” Layton volunteered, then lapsed into a stare. A while later, the young temple escort on the tailgate shook his head and said: “I don’t understand why they did it this way. They could leave any time they want.” It seemed the temple was generous: It willingly provided passports to those who wished to leave, and advanced $5000 to help defray transportation costs. We’d also just seen the warm, cheerful embraces between some of those leaving and some who were staying.

At the temple-exit guard post, the truck was halted. A black man with a “corn rows” hairstyle came up to the rear of the truck. Joining him was an older black man who fingered something in his right pocket.

The younger man demanded that everyone in the truck move aside. He apparently was searching for his wife, who had carried away their child that morning, hoping to escape the settlement. But she wasn’t in the truck and the men left. When the truck was allowed to pass, we all breathed easier. Some had the distinct impression that the two were close to opening fire on the truck. As we rode onto the black gravel, jungle-bordered runway, a small six-passenger Cessna was parked to one side of the corrugated metal shack which served as the airport terminal.

A second plane, a Guyana Airways 24-seater, was coming in for a landing. At the far end of the strip sat a yellow government plane. Its nose wheel had been broken the week before and four soldiers were guarding it with M-I6 rifles. As the larger plane landed, the temple truck, with several persons in the back, started to advance. Alongside it was a red tractor and trailer seen earlier at the mission.

Some of those leaving the temple eyed the vehicles with suspicion. NBC reporter Don Harris said coolly: “I think we’re in for some trouble.” Seating assignments were chosen after Ryan briefed the press on the knife attack and credited Mark Lane with saving his life. Ryan clearly was in good spirits. He was within a few minutes and a few yards of accomplishing his goal: to get out temple members who were afraid to leave or possibly held against their will. First the Cessna was filled, with Ryan frisking each boarder looking for guns and knives. Layton, who was insisting on taking the first plane, slipped to the other side of the plane before he could be frisked. When that was pointed out to Ryan, Layton contended he already had been frisked. Yet he submitted to a new search, then returned to his seat.

Meanwhile, the tractor, with several men in the trailer, rolled toward the terminal shack and halted a short distance away. Quietly the men with the tractor motioned aside a group of curious Guyanese children and other bystanders. Some of the defectors told me later that the men in the trailer were members of Peoples Temple.

“It looks like trouble,” I said to Greg Robinson, but he kept on shooting pictures.

As rapidly as possible Jacqueline Speier was signing on passengers at the fool of the boarding ladder while a reporter helped her check for weapons. The closest thing to a law enforcement official — a pleasant young policeman with a pink shirt and a 16-gauge shotgun — was disarmed by temple members. Then, with heart-stopping suddenness, the first shot was fired. I didn’t see who fired the shot but the sound came from the tractor and trailer. A loud series of pops echoed across the field.

“Hit the deck!” someone hollered as we scrambled over the gravel to the far side of the plane. I dropped to my belly. A bullet ripped through my left forearm. Another hit my wrist and knocked off my watch.

They were shooting to kill, not just to stop us from leaving. Springing to my feet, I ran 40 yards across the runway. Volleys of shotgun, rifle and pistol fire kept coming. I dived headlong into the three-foot-tall grass.

I crawled until I came to taller bushes and brambles, clawing my way into a pocket in the brush.

I stopped and listened. The shots still were popping at an amazing clip. I could still hear the groaning and crying of the targets.

Though I couldn’t see over the tall brush, I could hear the shots become less frequent. Then there were just a few.

My arm was gushing blood so I stripped off my belt and pinched down the biggest wounds.

I heard a few more shots and saw the tractor pull away. After they left, I crept out of the bush and saw five bodies around the plane. Other people were injured. Greg’s body was near the boarding steps with his camera bag and cameras scattered around him. There was a gaping wound in his shoulder and possibly his ribs.

Ryan, his thick grey hair bloodied, was near the front of the plane. Harris, a Los Angeles-based NBC investigative reporter who covered the fall of Saigon and the Nicaragua rebellion, had been killed. It was Harris who had been contacted by the first two groups of temple members expressing a desire to leave. Also dead was Bob Brown, the NBC cameraman and the kind of guy who loved action stories.

Patricia Parks had her head shattered before her husband’s eyes. Five others were wounded seriously. Speier’s right leg had a gaping wound, and her arm was injured. NBC sound man Steve Sung had chunks of one arm blown away. Anthony Katsaris, brother of Jim Jones’ aide Maria Katsaris, was wounded in the chest.

Vernon Gosney and Monica Bagby, the two temple members who asked for help in the note, also were seriously injured.

After the massacre, Layton strolled back to the area.

“He started firing at the front and missed the pilot,” said Dale Parks, who left the temple Saturday. “He hit Monica and Vern. He fired at me, but it misfired. I jumped up and fought for the gun. He went over the seats in a somersault and I flipped out of the plane with him. I got the gun. I tried to fire — but nothing happened.” Layton later was taken into custody by Guyanese authorities who seized a .38-caliber pistol and turned it over to US Embassy officials. By nightfall, the seriously wounded, some of them on litters provided by the community, were sheltered in army soldiers’ tents. The rest of us were accommodated in a private home.

“We were so scared, too, man, that they’d do this to you,” said one of the people who took us in.

Guyanese civilians set up a guard station for us, standing watch all night armed with only a shotgun, a machete and a long-bladed knife. More than a few bottles of rum were consumed or poured on wounds. We used curtains for bandages. Every loud sound put us on edge, with some wondering aloud: “Will they come back to finish us off?” The pilot had radioed for help after the shooting, but during the night the only thing we heard were more rumours about the imminent arrival of Guyanese troops and medical evacuation planes.

During the long night, the temple defectors told us that all the horror stories about Jim Jones and the church were true. There had been underground boxes to punish the lazy; public beatings; drills where guns and bows and arrows were hauled out on call of “white knight,” and plans for mass suicides. Yesterday morning 100 Guyanese troops came by train from Matthews Ridge, walking the last several miles as a precaution against sabotage or attack. Then two Guyanese medical evacuation planes flew us to the capital city of Georgetown, where a U.S. air force C-141 took us to Andrews air force Base near Washington, DC, stopping off on their way at the Roosevelt Roads Naval Base in Puerto Rico.

Five were dead, five seriously wounded, five suffered relatively minor wounds, nine were unhurt, and six were believed lost or hiding in the dense underbrush along the Kaituma River.

All these lives were wasted and I don’t know why. I keep remembering what Jones had said in the pavilion. “Destroyed,” he said, “from within …”

— Courtesy of The San Francisco Examiner