Interpol lists 60 Australian artworks missing from Sidney Nolan, Pro Hart as crims cash in

One of Australia’s most prized paintings has been snatched in deeply mysterious circumstances as crime gangs, bikies and drug dealers target Australia for lucrative art heists.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Sidney Nolan’s prized painting from his “Mask”series was supposed to be a drawcard for one of the nations’ fast-growing university art collections. But it seems the allure of the coveted canvas proved so great, it was snatched by persons unknown – in deeply mysterious circumstances.

The disappearance of the artwork, worth at least $100,000, should have been front page news. Interpol was alerted just in case the sticky-fingered thief tried to cross an international border with it.

However, the details of the theft from the University of Canberra Art Collection have never been made public until now.

It is an example of how art crime often goes “unrecognised, unreported and unsolved”, according to Australian Forensic Art Historian, Dr Pamela James, and is compounded by a wall of silence.

The FBI has estimated the lucrative illegal trade in art is the third-largest international criminal activity – after drugs and arms trafficking – generating millions of dollars a year, even in Australia.

Bonnie Magness-Gardiner, the head of the FBI’s art crime squad, believes this particular crime has a special allure for the public.

“It may be because so many of these major heists have been visualised formally in the movies, and there’s this glamour of Cary Grant or Pierce Brosnan as the thief who is highly cultured and gorgeous and has beautiful clothes and moves in a very high social setting. The reality, of course, is quite different. They tend to be burglars with no particular interest in art,” she has said.

James says it is the most “extraordinary and paradoxical criminal enterprise” and a world inhabited by perpetrators such as organised crime gangs, bikies, shady dealers, unscrupulous gallery owners, and opportunists like drug dealers hoping to make some quick money.

“Not the world most of the populace associates with high-end art,” she said.

Mafia and terrorist organisations are also known to be involved using stolen art to launder money or finance their activities, according to a report by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO).

AUSTRALIAN ART HEISTS

In Australia, art heists are a fast growing crime, but they are slipping under the radar of law enforcement. Most state and territory police do not keep statistics on how many art works are stolen each year.

Victoria is the exception, and the Crime Statistics Agency has revealed that almost 600 paintings have been reported as stolen in the past five years.

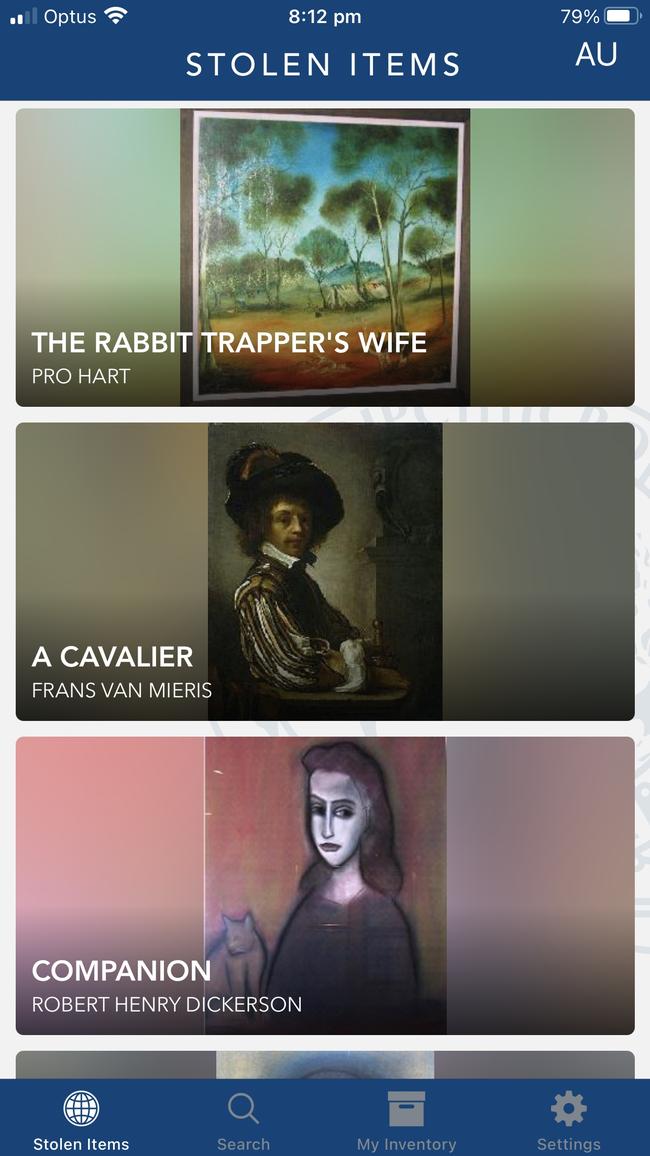

Interpol has launched a register called ID-Art containing details of stolen art works from around the world.

Australia has almost 60 items registered, including the prized Nolan painting entitled Mask VIII, as well as line drawings by Pablo Picasso, and paintings by David Boyd, Robert Dickerson, Pro Hart and Marc Chagall.

ID-Art also lists the 17th century Dutch masterpiece by Frans van Mieris, titled A Cavalier, which was stolen from the Art Gallery of New South Wales 16 years ago.

But the register does not include the millions of dollars’ worth of other works by the nation’s most celebrated artists, including Robert Dickerson, William Dobell, Tom Roberts, Arthur Boyd, Russell Drysdale and Hans Heysen, which have been brazenly stripped from the walls of collectors and galleries in daring robberies, never to be seen again.

”When art and crime mix, a wide spectrum of illegal behaviours come on to the screen — forgery and fraud, theft and extortion, money laundering, document and identity fraud,” the former director of the Australian Institute of Criminology Adam Graycar once wrote.

SALAD DAYS

As the price of art exploded in Australia and the rest of the world in the 1960s and ’70s, it became fashionable to pay huge prices for collectors’ pieces.

James said it was the first time pieces of art were worth more than diamonds, and that was hugely attractive to criminals.

Dr Chris McAuliffe, an Emeritus Professor of art from ANU, said he recalls stories of the brazen daylight theft of Heidelberg School works from the then-Melbourne Teachers College at Melbourne University.

“It does seem that the 1970s were, sadly, salad days for art thieves,” he said.

In August 1978, a thief brazenly cut from its frame Tom Roberts’ 19th century masterpiece Wood Splitters and walked out with it under his coat.

That painting was returned to the gallery nine months later, following ransom negotiations with an intermediary in Sydney, according to a book by art historian Dr Anne Beggs-Sunter.

The following year, Victoria’s biggest art heist was committed when thieves stole a million dollars’ worth of artworks from the renowned collector Joseph Brown’s gallery in South Yarra.

They took William Dobell’s The (Not Quite) Landlord. Arthur Boyd’s Wheatfields at Berwick, Russell Drysdale’s Tree Form Condor’s Spirit of the Desert, Tom Roberts’ Australian Landscape, and John Peter Russell’s Fishing Boats at Goulphar.

None of those works have been recovered.

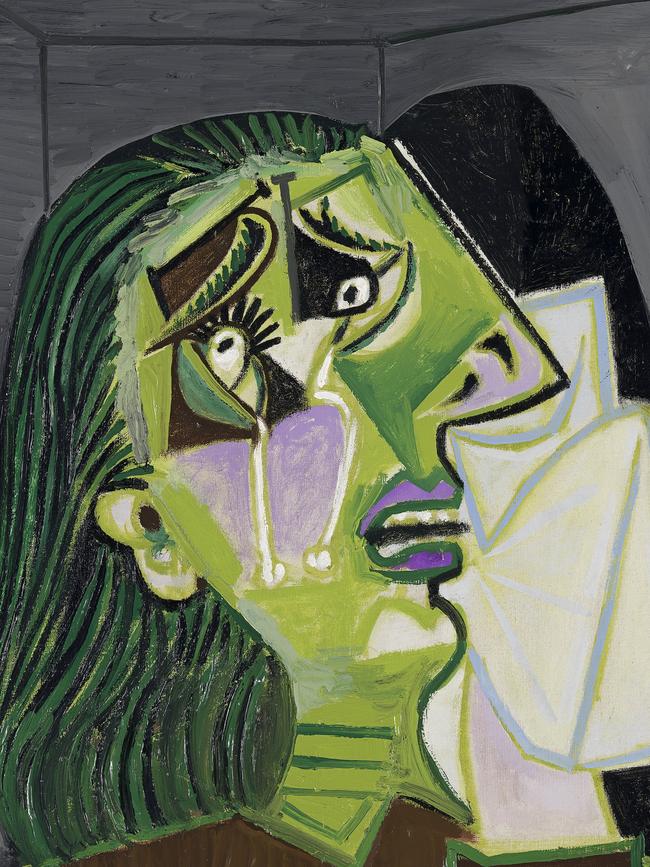

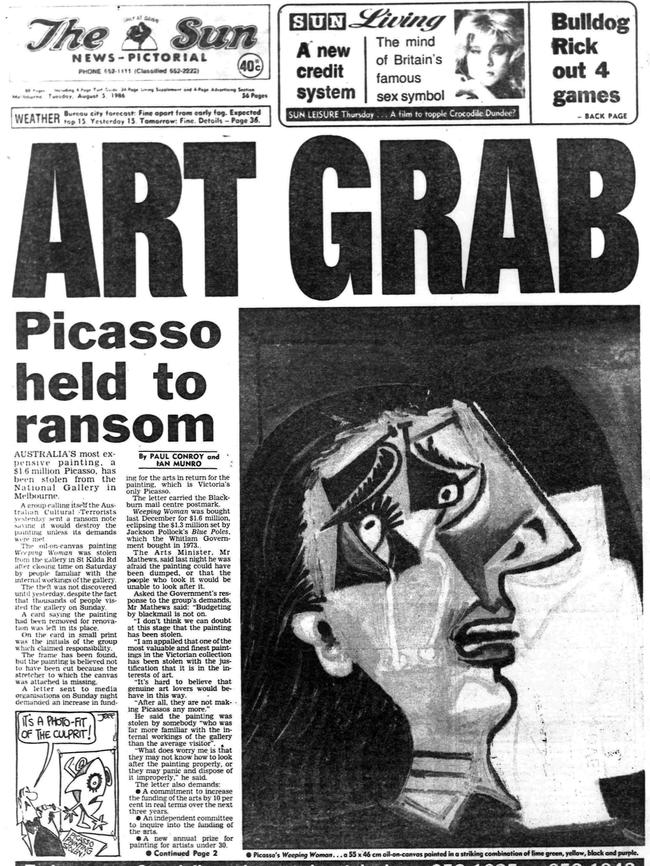

Then, in 1986, came the most notorious art theft in Australia. The Picasso Weeping Woman was stolen from the National Gallery of Victoria and held for ransom. That painting was eventually recovered.

The mastermind of one of Australia’s biggest art frauds, Ronald Coles, was jailed in 2012 for almost five years after pleading guilty to selling $8 million worth of artworks – through his now defunct Kenthurst Gallery in NSW – to investors unaware their paintings had already been on-sold to others, or belonged to someone else in the first place.

But James said art crime is not always so public and that is why it has been labelled the invisible crime because, like the theft of Nolan’s Mask VIII, galleries often don’t report or talk about a theft because it could reveal their security is insufficient and other galleries or potential donors wouldn’t loan or bequeath items to them.

“In the case of private collections, the owners may not want to draw public attention to the value of their collections,” she said.

“It is not unheard of that sometimes galleries don’t notice a missing piece for months, making the quick detection of an artwork that has been stolen, much harder to resolve. In addition, the art market can unknowingly pass on stolen or fraudulent art and the criminal art market operates in a unique way.”

FBI TOP TEN ART CRIMES

That may have been what happened 16 years ago when The Cavalier was ripped from the walls of the Art Gallery of NSW. The robbery of Frans van Mieris’s work, owned at the time by art collector John Fairfax, is listed by the FBI as one of the world’s top ten art crimes.

PHD student and art crime researcher, Vicki Oliveri, who did her honours studying the Cavalier theft, says the oil painting was the size of a magazine and easily concealed.

Ms Oliveri said it was not known exactly when the painting was stolen – CCTV was not working in the gallery and the guards didn’t notice when it was taken. At first the gallery staff thought it might have been moved. The police weren’t called until at least two days after it went missing, and then they didn’t turn up until the next day.

It could have given the thief time to whisk it out of the country.

However, Oliveri said a private detective hired to track down the stolen piece believed it had remained in Australia after communications were received by someone tracked down to northern NSW.

“I find myself, when I am looking at real estate photos, or photos of people’s homes, looking at the art in the background. You never know,” Oliveri said.

One of the world’s best known art detectives, the London-based Julian Radcliffe, would agree.

He has recovered numerous priceless pieces around the world, many on a chance or a rumour, including a lost Cezanne which was valued at $30 million when it was stolen and recently resold for $60 million.

OUTPOST FOR STOLEN ART

Radcliffe has also recovered millions of dollars in stolen art and cultural works sent to Australia from the UK in shipping containers by criminal gangs.

His agency, The Art Loss Register (ALR), is an international searchable database of stolen, looted, missing, and at-risk art and antique items. It is the world’s largest registry of stolen works. They work to track down artworks which would otherwise probably not be found.

Radcliffe, like other art experts, said unfortunately art crime is a low priority for police.

“It is seen as rich people stealing from rich people and insurance pays,” he says.

And so the recovery rate is very low – about 10 per cent.

Radcliffe’s operation, however, has one of the highest recovery rates in the world.

But he says it is “not all Rubens and Rembrandts”. Radcliffe says his agency also tracks down expensive and sentimental items such war medals and watches. He has just solved the mystery of an expensive Rolex Submariner watch stolen from an Australian man while he was visiting Paris. The trail led to a London auction house and a seller in Dubai.

Radcliffe also discovered a criminal gang in Britain plundering art and antiques “on a huge scale” and systematically smuggling container loads of loot into Australia.

Over the years, his team found a vast collection of bronze statues, stolen during a truck hijacking between Belgium and France, for sale in a Melbourne auction catalogue. They were returned to the owner.

A rare children’s Austin pedal car was stolen in England and also found in Melbourne at an auction. So too was an expensive porcelain collection shipped by the same bunch of criminals.

They also located a highly valuable Madonna and Child painting which was looted in Poland in World War II. The painting was returned recently to the heirs of the original owners, who now live in Sydney.

The ALR has numerous items listed as stolen from Australia, including a Marc Chagall lithograph, an Aboriginal Petroglyph (rock carving) which was stolen from an ancient Tasmanian site more than 20 years ago.

But there are many more art heists that go unreported. And Radcliffe said if Australians want any chance of getting their valued pieces back, they need to register them as stolen.

DIRTY MONEY

James said stolen art and legal art follow the same channels through auction houses, or secondary markets and it can create the perfect storm.

“It is a way to launder dirty money while building up a provenance for a piece. Sometimes there are third party bidders. They are laundering money and building legitimacy. I have been stupefied by what some people can get away with,” said James.

In a unique case, 46 years ago, 27 paintings by Australian artist Grace Cossington-Smith – an entire show – were stolen and have never been recovered.

Even though the only visual record of what was in the exhibition also mysteriously disappeared, James believes that using the titles of the work, their dimensions and techniques – and auction records – it would be possible to track if they had been inserted back into the legitimate art market. However, it would be impossible to prove in court.

James believes, with some dedicated team work, some of the paintings could be recovered.

When James was lecturing in cultural and social analysis at the University of Western Sydney School of Humanities and Communication, she ran a workshop with her students to try and track down the Cossington-Smith works. She thinks they found possibly three of them still circulating in Australia, using auction records.

While the trail has gone cold for many works, the market remains hotter than ever, especially with no financing regulations or reporting mechanisms to find crime or money laundering in the art world.

ART CRIME SQUAD

And while stolen art may appear on law enforcement wanted lists like Interpol, is anyone really searching for them?

James, who has been an expert witness for police, has long campaigned to pull together an art crime squad in Australia. She ran the first International symposium on art crime in Australia involving the FBI art crime team, Interpol and Australian law enforcement.

James says art crime is not a priority in Australia, unlike Europe and the US, and police here simply do not have the time or the expertise to put into it.

In a very rare twist, it can be revealed Nolan’s stolen Mask VIII has been recovered and, without explanation, is again hanging in the University of Canberra art collection.

The ACT police said they received a report of five pieces of art being stolen from the library at the UOC in 2001.

A spokesman said “following investigations and a call for information the matter was finalised with no arrests made”.

The ACT police reported the stolen artwork to Interpol through an Australian Federal Police Liaison officer. It remains listed as stolen.

The ACT police have no record of being notified that the painting has been recovered.

There are three possible explanations according to art experts – it was embarrassingly misplaced, it was an insider job, or it was returned after a ransom was paid. All are plausible given the history of art heists in Australia.

A spokeswoman for The University of Canberra said no one remembered anything about it and declined to comment further.

Do you know more? Email natalie.obrien@news.com.au