Brutal Middle Eastern gang DK’s Boys’ bloody rise and fall in 1990s’ Sydney

As Middle Eastern gangs took violent hold of Sydney suburbs and DK’s Boys ran the drugs trade in Kings Cross, police struggled to break their grip. A bloody coup saw the beginning of the end — but an innocent boy would be killed and a courageous cop shot.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was the gang war police didn’t see coming.

During the 1990s, Lebanese-Australian gangs took hold of Sydney.

By the end of the era, they had effectively taken over whole suburbs in southwest Sydney with criminal enterprises trading in drugs, car-rebirthing and extreme violence.

Telopea Street, Punchbowl was transformed into a 24-hour drive through drug shop and the neighbouring suburbs of Lakemba, Greenacre and Wiley Park were notorious for kneecappings and public shootings.

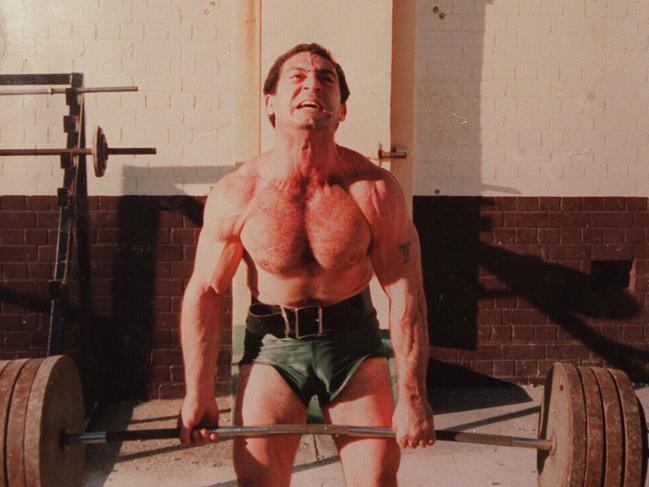

Across town, the notorious Kings Cross glitter strip was the stronghold of mostly Middle-Eastern gang DK’s Boys, led by standover man, Danny Karam.

Strings of murders left a public terrified and police struggled to regain control.

Victims and their families were too scared to provide police with information, making investigations near impossible.

Police Tape podcast: Inside the toughest crime gangs to crack

Battle for Cabramatta: How ethnic gangs terrorised Sydney

This was a new kind of criminal, unlike the Australian and Italian mafia groups police tackled previously, these gangs were unparalleled in their propensity for violence and resorting to gunfire over fists. They displayed a complete disrespect for authority and intimidated police who arrested them.

Second and third generation migrants, whose parents had immigrated during the ’70s and ’80s after the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War, these were kids who didn’t feel welcomed by Australian society.

But dangling before them was a lucrative lifestyle that promised fast money, street-cred and women — for many it was too enticing to resist.

Karam was one such crim.

From a young age he decided playing by the rules wasn’t for him — when he was hired by McDonalds as a teenager, Karam locked his manager in a cupboard.

He was in and out of jail during the ’80s and early ’90s with convictions for drugs, serious assault and breach of parole.

By the time he was released in 1995, he had built up a widespread criminal network, and he set about taking over the Kings Cross drug trade.

His timing coincided with the Wood Royal Commission into police corruption which some have theorised distracted police to such an extent, Karam was able to secure his foothold.

New life: Baden-Clay mistress’ new identity half a world away

‘Bring it on’: Cops stand form against firebombs and bricks

Although a heroin addict, Karam ran his empire on cocaine.

He set up mini gangs to operate beneath him. Each was overseen by a manager who oversaw several street drug runners, usually teenage boys between 14 and 17 years of age.

Tony Rashid was once one of Karam’s right-hand men before becoming a police informer.

He explained how the operation worked.

“We’d go and buy amounts of cocaine. We’d take that cocaine to a hotel room. We’d cut the cocaine, usually with pseudoephedrine and we’d get packets of Disprin, empty out the contents, fill it up with cocaine and place them in balloons, tie them up,” Rashid revealed in documentary series, Gangs of Oz.

“They carried these balloons in their mouth, no more than five at a time, that way if they’re approached by police they could swallow the caps.”

Safe houses were set up across Sydney and used to stockpile weapons and drugs.

The gang became a tight-knit family and as members progressed through the ranks they’d be presented with a gold rings, featuring a tiger head with two red ruby eyes, signifying promotion.

But Karam had brute methods for controlling his boys.

Those who disobeyed would be kneecapped, with a shooting estimated to have occurred once weekly. In one particular instance, a drug runner who didn’t call to say he wasn’t turning up for his shift, had his boss’s mobile number tattooed on his arm.

At its peak, the gang was turning over $30,000 per week, monopolising Kings Cross by violently forcing any rival gangs to pay “rent” to Karam to trade.

But Karam did little of the dirty work himself, instead commissioning his second-in-charge Michael “Doc” Kanaan.

Unlike other crims, Kanaan didn’t come from a hardluck background and attended private schools where he was a promising student. He aspired to a career with the Australian Federal Police but when he was ineligible due to an assault conviction, he became involved with DK’s Boys in 1997.

On 17 July, 1998, Kanaan drove to a cafe in the inner-west suburb of Five Dock to standover a rival group involved in car-rebirthing. He was accompanied by gang members Shadi Derbas, Bassam Kazzi, an unidentified man and another male known by the pseudonym Alan Rossini.

As the men made their way back to the city, they spotted an altercation between friends Ronald Singleton, Michael Hurle and Adam Wright outside Five Dock Hotel.

“Come on fellas, punch on,” Rossini yelled, urging Singleton to make a racist remark.

A fight ensued and Kanaan fired at least four shots, killing Hurle and Wright and injuring Singleton.

The murders marked the beginning of a downhill spiral for Kanaan and his cohorts who were becoming increasingly violent and out of control.

On 13 October, 1998, Kanaan and DK Boy Saleh Jamal, shot builder Elias ‘Les’ Elias in the buttocks at Greenacre over a dispute over a gun.

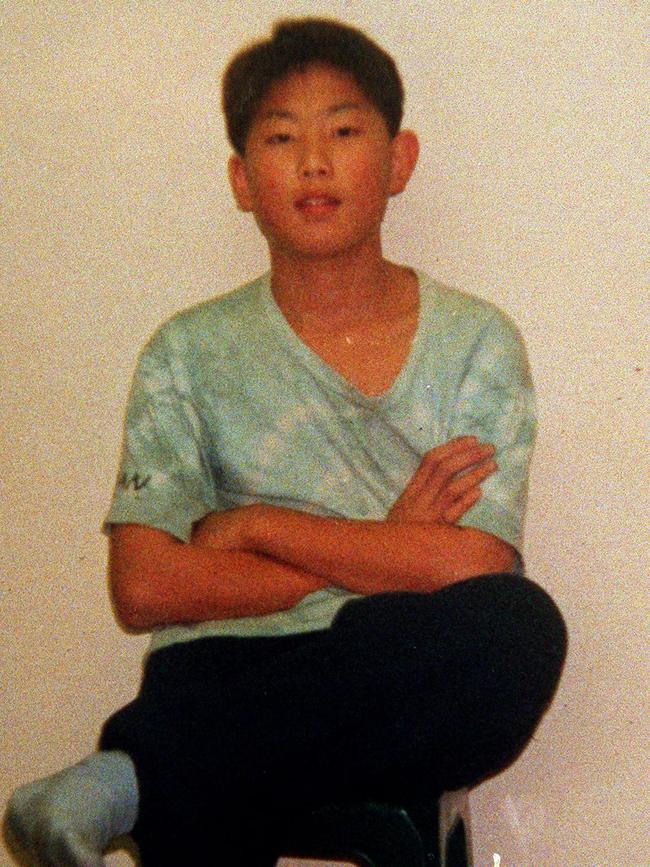

Four days later, 14-year-old schoolboy Edward Lee was killed while walking to a birthday party on Telopea Street, Punchbowl.

As Lee and his friends unwittingly walked through the turf of a group of mostly Lebanese teens, a fight broke out and Lee was stabbed to death by 15-year-old Mustapha Dib.

The murder caused shockwaves as a senseless example of rising gang violence and intimidation. Despite more than 100 people seeing the incident not a single person came forward.

Kanaan had links to some of the perpetrators and organised for Mustapha Dib and his brother to be transported to Queensland to create alibis.

Less than two weeks later, bullets rained through Eveleigh Street, Redfern.

After two Lebanese men were attacked by Aboriginal inmates inside Lithgow Prison, it’s alleged Kanaan organised a drive-by shooting on the well-known indigenous area as retaliation.

Thirteen rounds of ammunition were discharged into two houses as innocent occupants hid under their beds.

By December, Karam’s gang had begun to turn on their leader, under Kanaan’s influence.

Despite DK’s Boys raking in an estimated $30,000 per week, Karam was keeping most of the profits for himself. Kanaan was eager to take over the drug business and was becoming increasingly paranoid Karam would out him for the Five Dock murders.

He hatched a plan to kill him.

On 13 December, 1998, Karam arrived at one of the gang safe houses on Riley Street in Surry Hills.

While Karam was being buzzed in by Rossini, Kanaan and other gang members exited through the back door and waited in the dark to ambush him.

When Karam made his way out of the building, 22 shots were fired from three different weapons and Karam was shot dead.

Kanaan had taken control of the gang but they were now under intense scrutiny from police.

In an attempt to shift the attention, Kanaan ordered the murder of underworld figure Tongan Sam, who worked for the notorious Ibrahim family, hoping it would look like a retaliation hit for Karam’s murder and move suspicion off DK’s Boys and onto the Ibrahims.

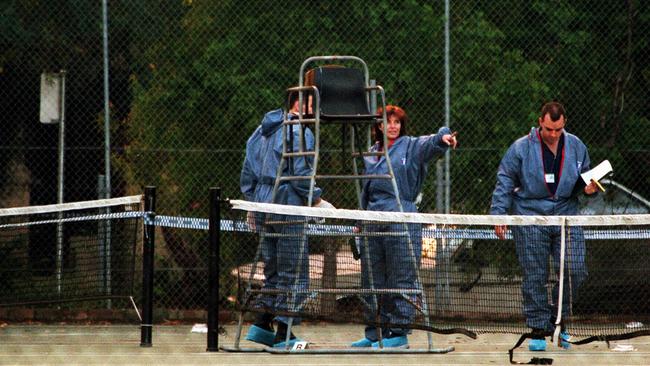

While Rossini, Kanaan, El-Assaad and Mark Cheikh scoured Sydney’s inner-Eastern suburbs looking for Tongan Sam on 22 December, 1998, a police car noticed their vehicle acting suspiciously. When the car refused to pull over, the men were pursued to a dead-end outside White City tennis club in Paddington.

They ran from the car. Rossini and Cheikh escaped, while El-Assaad was tackled by Constable John Fotopoloulos.

Kanaan scaled a fence to escape, pursued by Constable Chris Patrech.

While Patrech was dangling midway up the fence, Kanaan took his gun and shot the officer in the wrist and leg. Kanaan then shot at Fotopoloulos but was wounded in the process, shooting himself in the foot. His injuries left him in a wheelchair for the next three years.

“What he did was absolute cowardice. We had a police officer climbing a wire mesh fence and he was stuck. He was like a spider in a web,” retired Detective Sergeant Stephen Page told Foxtel’s Crime Investigation Australia.

Kanaan was arrested at the scene and taken to hospital under police guard.

Weapons found discarded from the vehicle were later ballistically linked to the murder of Karam and other shootings.

Although Kanaan was released on bail the gang was under heavy surveillance.

A strike force was set up to collect a brief of evidence on the gang’s drug distribution, four murders and up to 20 drive-by shootings and woundings.

In September, 1999, 150 police swooped on homes in southwest Sydney to arrest key members of DK’s Boys.

However, when the search warrant was about to executed on Kanaan’s house at Belfield, he barricaded himself inside for 32 hours, along with several family members and associates, before he finally surrendered.

DK’s Boys fell apart as police convinced key members to turn against each other, giving evidence in exchange for immunity. And with continued police focus, Telopea Street, Punchbowl, has returned to a safe suburban neighbourhood, now decades removed from its bloody past.

Kanaan is incarcerated at Goulburn Supermax, serving three life sentences plus 50 years and four months without the possibility of parole for the murder of three people and other offences.

“In the late 1990s, I can say that Michael Kanaan was probably the biggest problem that NSW police would have had at that time and if it ultimately wasn’t for his shooting at the White City tennis court and his later arrest for these and other matters, God only knows how many people would have been killed,” said Det Sgt. Page.