AFP hi-tech lab can track where Australia’s cocaine comes from

Andrew Parkinson has never been to where the world’s cocaine is made — but in the AFP’s special lab, he can track the exact source location of the drug flooding our shores.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Exclusive: He may not have travelled there but Andrew Parkinson can speak in detail on the hills, valleys and rainforests about Colombia and Peru and to a lesser extent Bolivia.

He knows the soils, the climate and even air density but he is no botanist, rather is the Australian Federal Police Forensics Special Operations’ Acting Coordinator Crime Scene helping colleagues track the exact source location of the cocaine flooding our shores.

Next generation of drug profiling technology is allowing like never before forensic specialists to establish where the coca leaf that goes on to become cocaine that is in Australia is grown, to such a finite point that is helping identify the growers and the cartel responsible for the trafficking.

“Our profiling can tell you samples grown in one valley and if you go to an adjacent valley we will tell the difference,” Parkinson said from his high-security laboratories in Majura on the outskirts of Canberra.

“Like any plant when it’s growing it sucks up nutrients, chemicals and other things from the soil it also gets affected by how high altitude it is, how close to the coast it is and while it’s growing, chemicals in that plant are getting produced in different ratios and different types of chemicals being produced.”

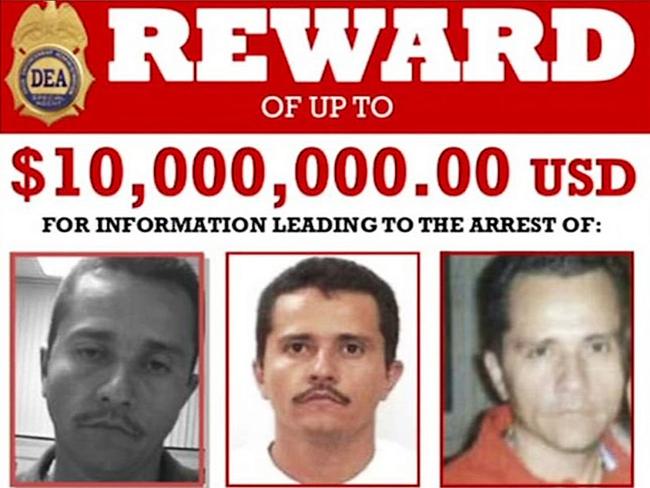

The sciences to breakdown a seizure of cocaine is backed by a database created by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in the United States that can link the growing and production to a specific cartel. While most of the cocaine is grown and produced in South America notably Colombia, Peru and Bolivia, significantly almost 80 per cent of cocaine being seized coming to Australia is controlled or influenced by cartels in Mexico.

“For me the best way to think about it is like wine, so if you think about Shiraz in the Barossa Valley and Shiraz in Margaret River it’s going to taste different that’s because it’s been grown in a different area and that’s because of the chemicals in the grapes, that’s a pretty good analogy to cocaine,” Parkinson told News Corp on an exclusive tour of the Majura facility.

“Also if you get the same grapes from one region and lot of people making wine, each wine is going to taste different because of the different processes that each of the wine makers do makes a taste difference.”

And it’s not just cocaine but MDMA (ecstasy) and methamphetamine (ice) seizures that can also be traced to broad region.

“Cocaine seizing in Australia is now in the tonnes, meth amphetamine in the multi tonnes so it’s always rising and I think that’s because Australia is so attractive for organised crime groups and the end users pay a lot of money for their drugs so it’s attractive for organised crime to target Australia,” Parkinson said.

“What’s important for us and our partner agencies all over the world is to understand what is happening, what are the trends, what are the routes the cocaine is making into Australia, where is it going via so if we know where the cocaine is most likely to have been grown and produced we can start using other information we are getting operationally from our officers to start building a picture of the likelihood of shipping routes and therefore we can alter some of our policies and interactions international … to stop the drugs coming to Australia in the first place.”

MORE NEWS

‘Nike Bikies’ lead frightening new crime wave

Inside Asia’s war on Aussie bikies

New twist hurts Cocaine Cassie’s parole bid

Uber easy: Dealers taxi cocaine to clients

Drug profiling sounds simple but it is not a quick process to get to the accurate geolocation of its growing and those most likely responsible for its production.

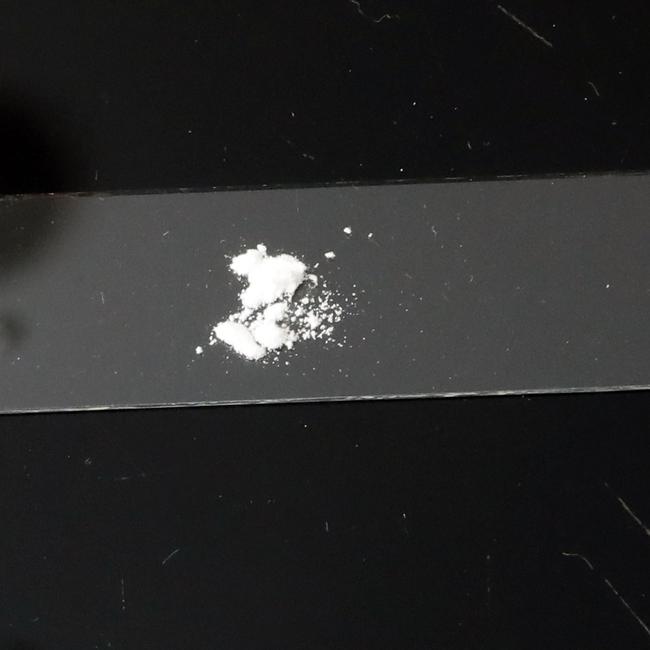

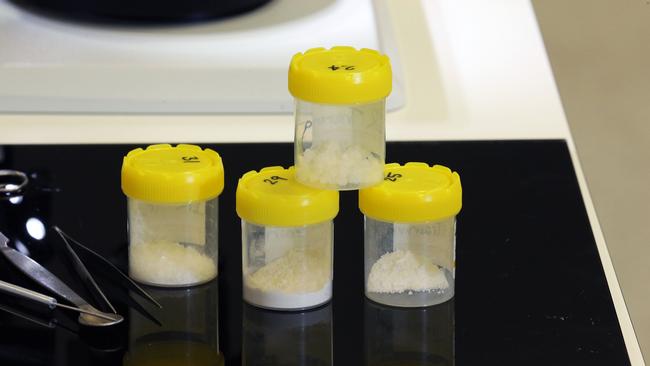

A sample of a cocaine seizure is taken firstly to Majura for preliminary checks then to the National Measurement Institute laboratory, part of the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, to profile the samples’ four chemical “signatures”. Here they determine the purity but high-level testing to pinpoint the drug’s origin.

Each seizure analytical investigation can take between one to two months to complete including purity analysis of two weeks and profiling of up to four weeks.

“It is a hectic workload,” Parkinson said, adding each job is prioritised on the basis of imminent arrests, public safety and criminal targeting.