YOU stand outside the house and it suddenly strikes you — how could something so extraordinarily brutal happen in a place at once so banal and ordinary? The house is at the corner of Jupiter and Richard streets in the beautiful Fraser Coast city of Maryborough, 254km north of Brisbane.

To get to it on the highway from Brisbane you need to cross the Mary River into Ferry St, turn left into Alice St, go past the Maryborough Golf Club, then turn left again at what used to be the Baddow Snack bar, into Jupiter.

There at No. 36, just down from the bus stop, sits this pedestrian one-level weatherboard home on a foundation of low-set bricks. At the front of the house is a small entrance patio that leads to the front door. Beside it is a door bell fashioned like a small ship’s anchor.

There is a lawn but little garden to speak of. Down the side is a carport with a roller door and two old concrete vehicle strips that lead in from Richard St. And at the back of the property is a larger, covered patio area that is embraced by walls of white 1960s fashionable breeze blocks, the shapes in the bricks a series of semicircles.

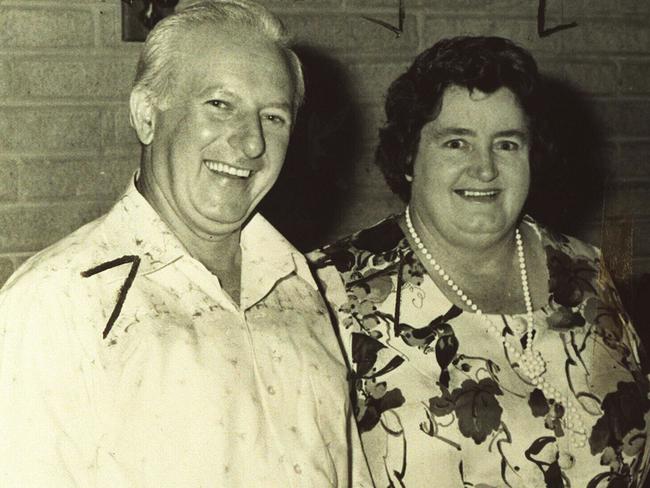

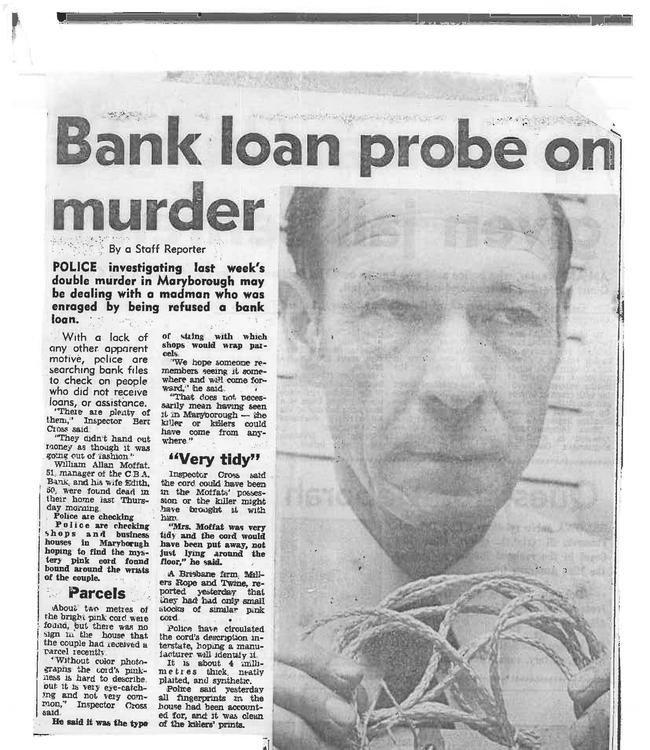

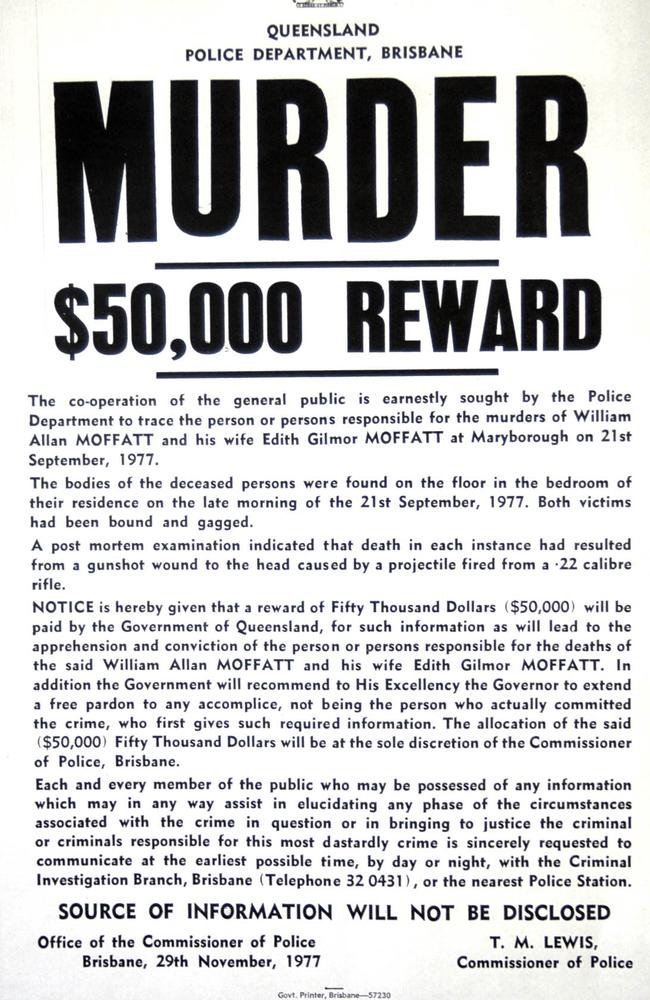

In this house, in the early hours of Thursday, September 22, 1977, humble local bank manager William (Bill) Alan Moffat, 51, and his wife Edith Gilmor Moffat, 49, both dressed in their pyjamas, dressing gowns and slippers, were hogtied at the end of their bed, gagged, and each shot in the back of the head with a single .22 calibre bullet. They died side-by-side, husband and wife, with their heads close together.

The double execution was, and remains, inexplicable. Two of the most unimposing, church-going, community-conscious, helpful, kind and respected people in town had met their end in a moment of exceptional violence. Two foreign worlds had collided here. And the callous and efficient method of execution belonged not to this historic sugarcane town with its manicured riverside parks and stately buildings, but in the wilds of Melbourne or the troubled suburbs of southwest Sydney. The shocking nature of the murders stunned Maryborough at the time, and its shadow has remained over this town decade after decade.

Those who remember the genial Moffats still ask: who killed our friends and, more importantly, why? As Maryborough police sergeant Bruce Hodgins says: “I’ve often said to the blokes at work, this is what you’d call the moment where the ultimate evil meets the ultimate innocence.”

IT’S ABOUT JUSTICE

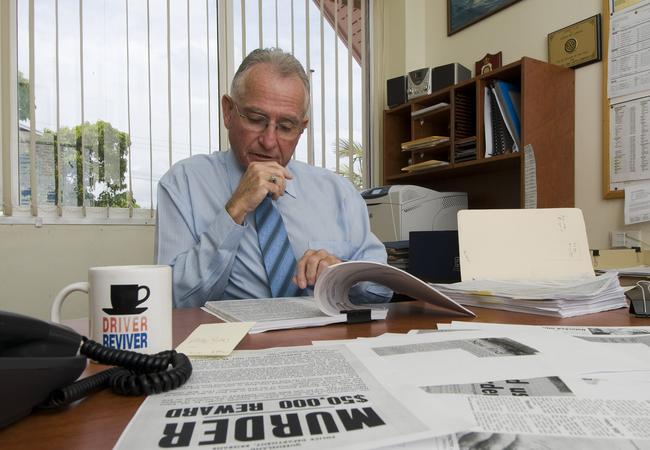

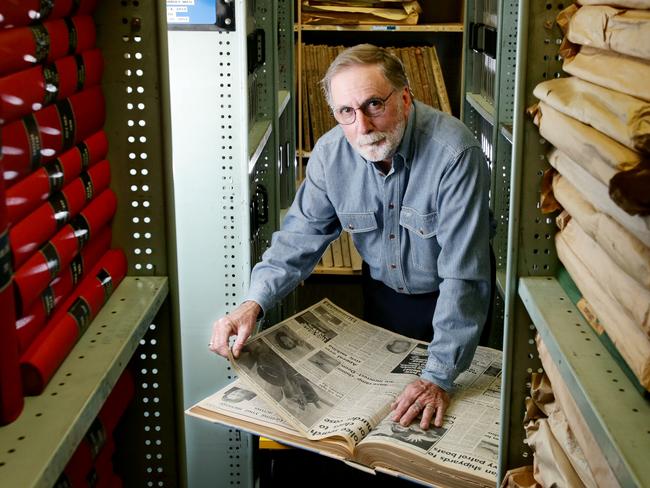

In a corner of the operations room inside the two-level Maryborough Police Station in Lennox St, within sight of the rump of the town’s City Hall, Hodgins’ workstation is straight out of a detective movie. He has his computer and a desktop crowded with old books, journals, ledgers and contemporary files, and on the wall there is a large pinboard crowded with old black-and-white police mugshots and newspaper clippings, and the haunting images of police photographs taken inside the lifeless house at 36 Jupiter St, after the murders in the spring of 1977.

This all speaks of pre-computer detective work. Of countless phone calls and paper record checks and police reports and records of interview typed on actual typewriters. As for Hodgins, he is lanky and casual and every inch the country copper. He speaks with a real geniality honed by 30 years of working outside the ambit of the city, and is not averse to a good laugh. He’s also sharp as a tack and reels off precise dates and facts about the Moffat case at will. For a year, his head has been firmly entrenched in the 1970s. For Hodgins, who takes compulsory retirement in March next year when he turns 60, this also may amount to some sort of last hurrah. A gift to Maryborough, perhaps. Could there be a breakthrough in the Moffat killings, almost 41 years after the event?

Hodgins was sworn in as a member of the Queensland Police Force in April 1978 — seven months after the Moffat slayings. By 1988 he was posted to Maryborough. And like all new police arrivals in town, he took a look at the Moffat files.

“The exhibits for the Moffat murders were still locked in our exhibit room here,” Hodgins recalls. “Clothing was bundled up and whatever, and the hard copy files of the case were here. I knew that there were copies in Brisbane, naturally enough.

“And of course like every detective you’re interested in what happens in your area and what homicide matters happen, but they were busy years and I had no chance to look at the murders then. It was 11 years after the matter for a start.”

Life and work got in the way until 2012, when Hodgins left the CIB and went back to uniform.

“That’s when I started looking at it again when I had a bit more time in uniform, and I realised it was silly — if you’re going to do something, do it properly, as my old man said,” Hodgins recalls. “I did a report to my bosses here locally who were very supportive, thank goodness, and I said there were a number of areas I wanted to look at in relation to the Moffat murders. But it takes time.

“I did an application asking if I could be taken offline for a few months to look at this. They agreed. I started about last July [2017, just prior to the 40th anniversary of the crime] looking at it. Then I contacted the Homicide Squad, of course, and I got access to certain other information they had down in Brisbane. And off I went.”

Hodgins says many fine detectives had looked into the murders over the years, but he felt guilty that no resolution had been reached. “You just look at it,” he reasons. “Here are two wonderful people, as they seem to be, and there’s no reason … we’re not talking about crooks here, but a gentleman who went out of his way to help other people, a bank manager, and his lovely wife who used to go to all the different functions and help on committees, and because of that they were executed at the base of their bed. It’s just not fair, you know?

“That’s what drove me, really. Ever since I’ve been here, every pub you go into you could talk about old murders or something that happens, and people reflect back to this unsolved murder.

“Especially this one. It seemed to affect a lot of people in that they saw themselves, they put themselves in the position of old Mr and Mrs Moffat. There they are, in their house, late at night, in their bed, woken, and whatever’s happened happened. And they’re found dead, shot in the back of the head. It’s not like a murder where you’ve got a drug-related matter out in the bush and they’ve argued over a drug crop or something.”

Night is gathering outside the police station, and you can hear through the windows the sounding of bells from the nearby City Hall tower and its four-faced clock.

“This is not about me,” Hodgins says, “It’s about justice. It’s about Mr and Mrs Moffat. It’s about the standing of this town.

“I’ve had people in their late 60s and 70s basically almost crying on my shoulder saying, ‘Please, can you please give us an answer?’

“They want to know.”

PILLARS OF THE COMMUNITY

On the last day of their lives, Bill and Edith Moffat did what they had been doing since they arrived in Maryborough in 1974. They engaged with their community. The couple had learnt to adapt to new places following Moffat’s peripatetic existence as a bank employee. Every few years he and his wife and their furniture would up stumps and shift to another Queensland town as his banking career progressed.

“They had transferred so many times, every three or four years, the poor buggers,” says Hodgins. “Their furniture in the house, you could see it had been moved so many times the cupboards had lines across them where they’d bounced around the back of these removal vans.

“He was in Kingaroy for three or four years before Maryborough, and before that … I know he started off in the Burdekin [in north Queensland], and that’s where he met his wife. Then there was Alpha [in the Barcaldine region, 400km west of Rockhampton]. Kingaroy. Maryborough. And several other places as well.”

Bill Moffat grew up in the Gold Coast region, winning a proficiency certificate as a teenager as a member of the 66th squadron of the Air Training Corps in Southport in 1943. By 1944 he was working at the Southport branch of the Commercial Bank of Australia and as a member of the relieving staff he was transferred to Mundubbera, 400km northwest of Brisbane. The South Coast Bulletin reported that he had been farewelled by Southport bankers, and was presented with a leather money belt.

By the late 1940s, Moffat was working for the bank in Home Hill, near Ayr, in the Burdekin region. It was here he met his future wife, Edith Gilmor MacKenzie. Curiously, a report in the Townsville Daily Bulletin on March 17, 1949, in its “Home Hill Notes” column, said that “Miss E. MacKenzie leaves on Friday night to spend a holiday in Brisbane and the seaside”. Two paragraphs later, the report said: “Mr W. Moffat of the Commercial Bank staff leaves on Friday to spend his vacation in the south”.

Moffat may have been taking his fiancee to Southport to meet his parents.

FROM BEENLEIGH TO ALPHA

By February 1951 Bill and Edith were married and living in Townsville, where Bill continued to work for the CBA. Within a few years he’d been transferred again, this time to Beenleigh, south of Brisbane, where he and his wife settled in Logan Rd. There, they entertained friends at their home, as The South Coast Bulletin reported in 1954. “Mr and Mrs Moffat excelled in entertaining their guests, the whole evening being one round of gaiety,” the newspaper said. “Several amusing competitions caused much hilarity; games and community singing were also part of the evening’s entertainment. “Dainty refreshments, which were much appreciated, were served buffet fashion at a late hour, during which a very happy time of fellowship was enjoyed. Time passed too quickly, and midnight found guests expressing thanks to Mr and Mrs Moffat for a most enjoyable evening.”

By the early 1960s, Bill Moffat had been transferred yet again with the bank to the tiny town of Alpha, more than 1050km northwest of Brisbane in Queensland’s Central West. While there, they befriended a young teacher, Eileen Mellor, who was on a 12-month secondment in the Alpha/Jericho area. “My year in Alpha was a lonely one for me, and if it had not been for the friendship extended to me by Edith and Bill, I doubt if I could have stuck it out,” Mellor later reflected. “I found Edith and Bill such a lovely couple, devoted to each other. They were loyal, trustworthy and honest people who worked tirelessly in the community for many organisations, and they would go out of their way to help and befriend any young person who was on transfer in this town which, at the time, was bereft of much to interest and occupy one’s time.”

Alpha was only about 53km from the village of Jericho, and on a regular basis Bill Moffat would drive there and offer banking services for the locals out of one of their community halls. He also did the banking for the local school, and met the husband-and-wife teaching duo of Jim and Patricia Isdale. The Isdales soon became good friends with the Moffats. “I asked them over for lunch one day,” remembers Patricia. “Bill was quiet and conservative. They both were. Having had no children of their own, there was not much show of emotion or affection. They were very kind and very thoughtful. We were probably the closest family they ever had.”

Just prior to Maryborough, Moffat had spent a few years with the CBA in Kingaroy, the home of premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, 210km northwest of Brisbane. “The CBA’s number one customer at that time was Bjelke-Petersen,” says one former bank officer. “I understand the premier and Bill Moffat went to the same church.”

When the Moffats landed in Maryborough in 1974 — by this time Bill, still with the CBA, had been transferred for around 30 years of his career — they quickly settled into the bank-owned property at 36 Jupiter St. He was proud to be manager of the CBA on the corner of Adelaide and Kent Sts, opposite the grand City Hall. And as they’d done countless times before, the couple joined numerous committees and groups that formed the fabric of the town.

“They were just living their average life like everyone in those days,” says Hodgins. “They were just normal battlers. Admittedly he was the bank manager but they weren’t on all that good money in those days, just on average money, and his wife, she did home duties, but they were heavily involved in the church. That was the same year that the Methodist and Presbyterian churches joined to become the Uniting Church, and it was around that time that the Moffats joined, so they were heavily involved in that.”

The Uniting Church was formed on June 22, 1977 — just three months before the murders — after the Congregational Union in Australia, the Methodist Church of Australasia, and the Presbyterian Church of Australia came together. Bill Moffat, as a bank manager, was tapped to look into the local mergers and how the churches could financially come together. He was also involved in the local Lions Club, the Rostrum public speaking club and the Boy Scouts, which had been an abiding interest since he was a teenager. And, just as they had done when they lived in Beenleigh, they enjoyed entertaining.

“They used to have dinners, progressive dinners, where they’d go around to a number of different people’s places and have a meal once a month,” Hodgins says. “It was very ordinary, basic things. I think Mr Moffat liked to have an occasional wine but he wasn’t much of a drinker. He had a number of wines at his house and he used to collect a few wines — not as a major collection, but just as something that he did.”

The Moffats had no children, and it was noted in the community how they were virtually inseparable. “They were always together,” says Hodgins. “If Mr Moffat had to travel to another bank to do an inspection or, you know, he’d often go to Hervey Bay or up to Bundaberg or Gympie, places like that, he would use the excuse to take his wife on a trip for the day and she’d enjoy it. They were pretty devoted to each other. There’s no evidence there was any third party involved in the marriage in any way, shape or form. They were just a lovely couple living their life.”

Elaine Mellor kept in touch with the Moffats when they moved to Maryborough. She visited Edith at the house in Jupiter St, in the suburb of Baddow, traditionally considered as safe as anywhere in Maryborough. “I remember her saying to me that she was not happy living there,” Mellor recalled. “She was always very anxious … staying on her own at night, when Bill attended a night meeting. She expressed [the] fact that she would have felt less anxious living closer into the heart of Maryborough.”

THIS ‘DIDN’T HAPPEN’ IN MARYBOROUGH

On the morning of Wednesday, September 21, 1977, the Moffats rose as normal and Bill made his way to the bank in Kent St in his Valiant Regal. Mrs Moffat stayed at home and, as was her habit, kept the house immaculately clean. She planned lamb chops for dinner that night.

Bill Moffat was at his desk before any other employees arrived for work. About 9.30am on that day, Moffat, a keen stamp collector, left the bank and walked to the Municipal Library where he gave a lecture to local philately enthusiasts. Moffat, on arriving in town, had soon become a member of the Maryborough/Wide Bay Philatelic Society that had been running since the 1960s. He himself had a substantial and valuable stamp collection. After the lecture he returned to his duties at the bank by 11am.

Moffat then worked on a loan application for most of the day, leaving briefly at 4pm with a client to inspect work done on the client’s house, before returning to the CBA and completing the local application. He was still at his desk at 5.30pm.

At the end of the day he returned to Jupiter St. Busy as ever, both he and his wife had meetings on that evening. About 7pm, Mrs Kay Hass arrived at the Moffat home to pick up Edith and take her to a charity fashion parade being held across town. Bill Moffat told her Edith was still in the shower so Hass waited in the lounge room. Fifteen minutes later the two women were on their way.

The Hasses had been good friends with the Moffats since they’d arrived in Maryborough. Only the previous Saturday, they had enjoyed a barbecue with the couple in their entertaining area at the rear of the Jupiter St house.

That night, Bill Moffat had his own meeting to get to. “He had to go to a meeting for the church, the structure and finances and everything else that was involved in this uniting of the churches,” Hodgins says.

Edith was dropped home by Kay Hass around 10.55pm. It was not known if her husband had already returned from his meeting.

“On the kitchen table were a number of church accounting books, which [investigators] thought maybe Mr Moffat had come home and perhaps done a bit more work for the church, they’re not sure, or maybe he just left them there after he got home from the meeting,” says Hodgins. “Nothing untoward happened at either meeting that Mr and Mrs Moffat attended; the fashion parade or the church meeting.”

The next day — Thursday — Edith, as president of the St Columba Ladies Guild of the Uniting Church, was due to chair a meeting of the guild at a hall in Russell St, not far from Jupiter St, at 9.30am. Her good friend, Jean Menadue, turned up on time for the meeting, as did many other ladies of the guild. “She noticed that … Mrs Moffat was not there,” an official police report later stated. “Shortly afterwards the Guild decided to start the meeting in the absence of … Mrs Moffat. About 15 to 20 minutes after the meeting had started, Mrs Menadue became concerned that … Mrs Moffat was still absent from the meeting, so she drove to … 36 Jupiter St and parked her car in Richard St, near where the street intersects with Jupiter St.”

Mrs Menadue walked past the garage door towards the back of the house and went through a small gate into the back yard. She called out to Mrs Moffat but got no reply.

Mrs Menadue noticed a few windows open between the back of the house and the covered entertainment area.

“She stated that these windows were well open and she could see the curtains flapping in and out of the house through this window,” the police reported. “She also saw [the Moffats’] pet dog [Bindi, a blue cattle dog/bitsa] lying on a number of blankets below this window … Mrs Menadue also saw a small stepladder leaning against the wall directly underneath the open window.”

BILL’S TARDINESS WAS UNCHARACTERISTIC

As she left the yard she saw three newspapers lying on the footpath and noticed a “full bottle of milk in a wooden box against the Richard St side fence”. With Mrs Menadue puzzled, another friend, Ruth Harriman, had telephoned the CBA bank looking for Mr Moffat and any news about his wife.

Young CBA accountant Doug Bell had arrived at the bank as usual at 8.30am and was surprised to see that Bill Moffat was not already hard at work, as was always the case.

Bell, who had been born in Maryborough but had experienced several transfers himself with the bank since he joined as a bright young 16-year-old in 1963, got along well with Moffat. Bell counted him as a friend.

When Moffat had not reported to work by 9am, Bell made inquiries of the staff. Nobody knew where the manager was. His tardiness was uncharacteristic.

Bell discovered that bank employee Sandra Potter had received a phone call from two ladies asking after Mrs Moffat. Did they know where she was? Bell twice telephoned the house in Jupiter St but it rang out.

At 10.30am, Mrs Menadue and Harriman popped into the bank and spoke with Bell. Both women asked him if he would mind accompanying them to the Moffats’ house to make sure everything was all right. He agreed.

They left in Mrs Menadue’s car, picking up pastor Maurice Harriman, Ruth’s husband, on the way, and arrived at the house about 10.25am.

The police report said: “Bell saw the deceased’s car in the garage and found that the bonnet was cold. He began to feel at that stage that something was wrong.

“Bell and [Mr] Harriman then decided to enter the house … Bell … then entered the house by climbing the small stepladder and a further call by him was unanswered.”

Bell says he can still feel the same chilling sense of dread when he recalls clambering through the window into the house.

“I called out to Bill and Edith but there was no response,” he says. “There they were in the bedroom. All you could see if you bent over them … behind Bill’s ear there was a tiny red mark. They were gagged with what looked like some of Bill’s CBA work ties.

“I knew they were dead. It’s a funny thing, but I looked at Edith’s hands tied up and I thought the cord was knotted very delicately, like a Boy Scout knot.

“But Bill’s wrists were bound so tightly you couldn’t see the cord. It just made me wonder if whoever did it had made Bill tie Edith’s hands together, and then the killer tied Bill’s.”

Shocked, Bell took out his handkerchief and used it to pick up the phone and call the police.

“I rang the local police station and one of the office girls answered the phone,” Bell recalls. “I told her that I was in a house and that two people had been shot and it looked like they were dead. She went all ga-ga on me.

“She got a policeman on the line. I told him and he started going funny. I asked them if Glen Taylor was on duty. He was, and he came to the phone. He told me to stay at the house and he’d be there in five minutes.

“I couldn’t get any sense out of anyone. This sort of thing didn’t happen in Maryborough.”

It was 11am. ■

NEXT WEEK: Part 2 — Gangster link to murder

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout