How bank teller turned cop Ross Barnett caught worst armed robbers in QLD history

They were two of Queensland’s worst bank robbers. These brazen bandits got away with millions in violent armed holdups, until Ross Barnett took them on and cracked the case.

Cold Cases

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cold Cases. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WILLIAM Orchard’s tone did not match his predicament. It was formal, instructional, as though he were dictating his memoirs, and the younger detective was there to take notes.

“We were going to chain them all together,” he mused, as he recounted what was then the biggest armed bank robbery in Queensland’s history. “It might sound … what’s the word? Grotesque? But we were going to do that to stop them from following us.”

Instead, Orchard had wrapped the chain around one guard’s neck, splashing fuel over the terrified man and the armoured van he’d been inside moments earlier. The men were shown a lighter. The message was clear. Obey or the chained guard would burn alive.

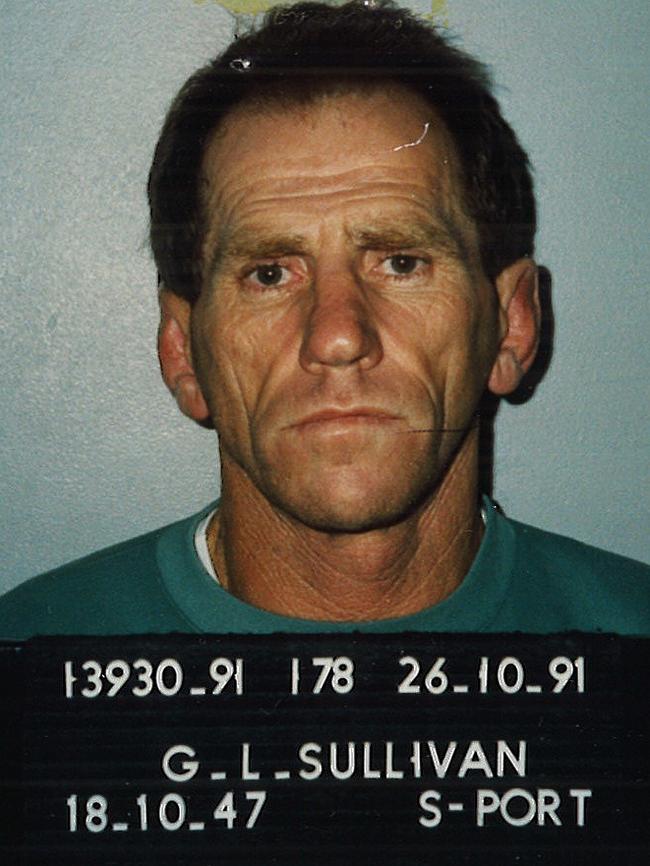

Orchard and his accomplice – his stepson and Australian league player Garry Sullivan – were armed. Their .38 Smith and Wessons had been flashed about. They had a tomahawk Orchard had used to disable the truck’s (two-way) radio.

Sullivan had grabbed another guard, using him as a shield as bags of cash were thrown from the back of the van.

They’d needed a shield to keep themselves safe, to stop the guards from firing at them, Orchard explained. But they’d been shot at anyway, as they’d fled with their loot. It had been very frightening for them.

“So we were lucky, to a certain degree, that we never got a bullet in the back of the head …” he told the detective in a recorded interview – the tape of which still exists. “Because I heard one go whizzing past … from behind. I don’t know whether you’ve had a bullet go past your ear or not?”

He spoke like a man recounting an experience he was sure was his alone. This near death experience, a victim of someone else’s recklessness. Detective Sergeant Ross Barnett paused. Orchard’s words hung in the air.

“I most certainly have,” Barnett said. “I know what it’s like.”

FAMILY TRADITION

This is the largely untold story of how a determined detective caught two of the worst armed robbers in Queensland history.

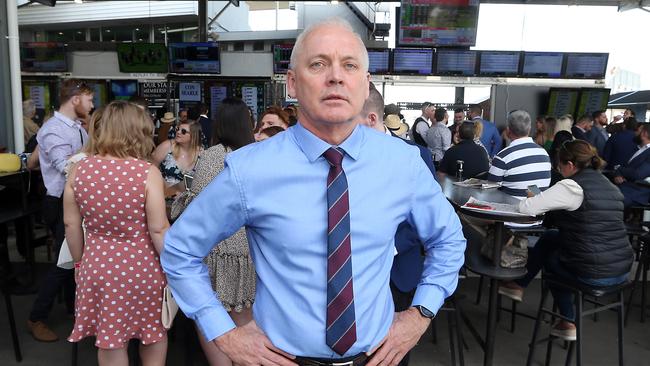

But to tell that story – a story that reminds him of his own mortality, that fills him with emotion and irreparable trauma – Ross Barnett needs to start at the beginning. When he was just 18. Fresh out of school and working in a bank. He’d wanted to be a copper. But the Queensland Police Service wanted recruits with life experience.

It was almost a Barnett family tradition – his father, brother and uncle were all police officers.

His job at the bank involved accompanying a teller from the branch at Broadbeach to a sub-branch at Mermaid Beach, the two men carrying a bag of cash down the street. Inside the bag, for “security”, was a gun that neither knew how to use.

Their route took them past a toilet block, where, one morning, two men in balaclavas were waiting. Barnett and his colleague were grabbed, bound and gagged and the money taken. Barnett remembers the blade of the knife cutting tape close to his skin. He remembers the terror of it, of not knowing how far they would go for the $4000 in that canvas bag.

He joined the police a year later, eventually working his way to the Armed Hold Up Squad. He’d wanted to work with armed robberies and find these men wielding guns and terror to feed their greed and get them off the streets. It was his passion. He had incredible empathy for the victims. And a total contempt for the cowardly perpetrators.

CATCHING A CRIMINAL

Harold McSweeney was a career criminal. An armed robber who would hit banks and armoured vehicles.

In March, 1991, an intelligence report warned prison authorities at the notorious Boggo Road Gaol that some inmates had been paying close attention to vehicles entering the grounds. Garbage trucks, the bread truck, the laundry truck.

The next day it happened: inmates took control of a garbage truck and used it to ram the front gates. A couple of the prisoners were caught almost immediately. One was on the run for a few weeks. McSweeney managed to lay low until May and while on the run he was suspected of committing armed robberies where shots had been fired.

It was a different era. Banks were hit with frightening regularity. Men with guns and disguises terrifying staff and customers for big money. Today, with significant improvements in security, this sort of violent robbery is almost non-existent.

On May 24, an armed McSweeney hit an armoured vehicle in the carpark of the Brookside Shopping Centre at Mitchelton.

He got away with $240,000, spraying the truck with bullets from an SKS rifle to prevent it following him.

“(He) had absolutely no reservations about firing weapons in public places,” Barnett says. “Whatever it took to get the job done. That was the sort of person he was.”

A day or two later, police received information that McSweeney was in Toowoomba. He was heavily armed, a closely connected underworld informant warned. A double shoulder holster with two concealable firearms. A shotgun and an SKS automatic rifle in the boot. “If you try to stop him he will shoot you” the informant had ominously warned. Barnett and other detectives were sent to Toowoomba with a surveillance team to find him. Which they did.

There were less rules around pursuits in the early 1990s. There was no full time Special Emergency Response Team to send to high risk arrests. Barnett and his partner spotted the armed robber and gave chase, screaming through roundabouts at 160km/h. No braking. They lost the surveillance team, foot to the floor, suburban streets screaming past in a blur.

Barnett was in the passenger seat when detective Peter Gray saw an opportunity and took it – he rammed McSweeney off the road. The armed robber’s driver’s side door jammed up beside Barnett’s passenger side door. Door handle to door handle.

And, as predicted and without a word, McSweeney opened fire. Barnett took a bullet in the hip as he scrambled across the front seat, throwing himself out the driver’s side. A bullet blew out the driver’s side window, whizzing past his head. Inches away.

“That was a very close thing,” Barnett recalls of that near fatal moment. All these years later, he says it’s still a hard thing to come to terms with. How close that bullet came. The detectives gave chase on foot. Barnett with a gunshot wound to his hip. He didn’t think about it at the time. It would hurt later. They had no idea whether McSweeney had more rounds in his two handguns. Whether he would turn and fire.

They didn’t catch him. But two hours later, he’d surrender – bizarrely, to a television crew who’d landed their helicopter nearly on top of him. A year later, he’d be dead. McSweeney was shot attempting to hijack a bus after escaping from court.

CRACKING A COLD CASE

Barnett was forced to take time to recuperate. More than he’d wanted. He wanted to continue his work in the armed robbery squad, so they gave him something to keep him busy: a cold case investigation.

From 1985, right up until March 1991, two men had been hitting banks and armoured vehicles between Brisbane and the Gold Coast.

By the time they were done, the pair would have carried out the six largest armed robberies in Queensland history. (That title would later go to postcard bandit Brenden Abbott).

Police knew little about the pair. There were two of them, one larger than the other. Those were the constants. The variables were many. Different disguises. Different vehicles. Sometimes they’d wear balaclavas. Sometimes rubber joke-store masks, made famous by the 1991 Patrick Swayze film Point Break. Except, instead of American presidents, these men wore rubber masks depicting old men with wild hair.

In May 1985 they’d stolen a car from a train station and driven it to an ANZ at Sunnybank.

They wore overalls, stocking masks and balaclavas. Floppy hats. One carried a shotgun. They burst in the front doors.

“Get down on the floor!” one shouted. They left with $27,000.

A month later, they were at it again. The Westpac at Palm Beach. Balaclavas and stocking masks. A jemmy bar and a sawn off shotgun.

One of the men jumped the counter while the other wielded the shotgun. They ransacked the safe, the tellers’ cages. Police would later find the getaway car burnt out at Loganholme. Amazingly, the bandits had stolen it nearly a year earlier from a car dealership.

That armed robbery netted the pair $91,000.

Their next was just five days later. A car stolen months earlier. Balaclava, stocking mask, gloves, overalls. A shotgun and a revolver. In through the front doors of the ANZ at Mount Gravatt. One man jumped the counter. The other went into the manager’s office.

“Get out of here and get down on the floor!” Then: “Come on, come on, open the safe!”

Terrified fumbling. A pistol prodding the manager’s back. A female teller was told to empty the cages. “Hurry up!” one of the men told her, jabbing a gun into her buttocks. They left with $24,000 in a sports bag.

In September they hit the National Australia Bank at Slacks Creek, using a car they’d stolen three months earlier. The two men left with a massive haul – $213,000.

The men weren’t linked to another robbery until July the following year. This time, they did things differently. At 5pm on a Monday, while staff were at the back of the building counting money for the next morning’s armoured van collection, a station wagon crashed through the bank’s rear doors. It took three attempts before the doors finally gave way and two men, masked and armed with a shotgun, burst in. Later, they’d admit the rear entry hadn’t been their plan at all – they’d got to the bank late and discovered it had closed for the day.

It was their biggest haul yet – $233,000.

In April, 1987, they targeted their first armoured van. They drove a Toyota HiAce van that they’d bought from a car yard under a fake name.

At 11.40am, a Brambles armoured vehicle pulled into the back of the ANZ bank at Coolangatta and two guards got out. One went to the counter to collect the money while the other stood guard in the foyer.

Moments later, two masked men, armed with a shotgun and a revolver, came in through the bank’s back doors. The man with the shotgun came up behind the guard in the foyer, pointing the weapon at him and demanding he get on the floor. The guard at the counter went to turn, but felt the barrel of a gun press into his back. He got on the floor too. The two men took the cash and left the same way they’d come in. It was a new record – $316,000, plus the two guns the guards had been carrying.

The following August they hit another van at the Commonwealth Bank at Sunnybank. They were getting more violent. One of the gunmen kicked a guard in the thigh, pointed a revolver at him. They left with $420,000 and the guns the guards had been carrying.

January, 1990. The Commonwealth Bank at Mount Gravatt. They used black spray paint to stop security cameras from capturing the robbery unfold before raiding the strong room, threatening staff with handguns. It was a comparatively small earner. Just $160,000.

Two months later, they were at it again. They accosted Brambles guards walking back to their van after picking up cash from the Westpac at Springwood. Another two guns and $139,000.

Their biggest haul would come in April 1990. They used a car they’d bought from a Kedron car yard a month earlier, giving the salesman a fake name. They got out the old man masks, a handgun and a shotgun and waited at the back of the Sunnybank Hills Shopping Centre for the Brambles van to pull in. When the guards got out to open up the back, the gunmen pounced. The guards were told to get on the ground and hand over their guns. They did. They used a ladder to climb on to the roof and used a tomahawk to slice off the aerial. He seemed to know which of the two aerials was live and which was the dummy. Without it, the rear guards could not call for help.

Still on the vehicle, the gunman took a container of fuel and poured it over the roof, the petrol spilling down the front windscreen and on to the ground. He climbed down, took a length of chain and a padlock and wrapped the chain around one guard’s neck.

The terrified guard lay on the ground, the fuel all around him, the gunman’s foot on the back of his head.

The bigger of the two bandits said to the other guard: “Tell him if he doesn’t get the bags out, I’ll torch the truck. I know what you got in there. Get it all out. If you don’t, we’ll light a match.”

“Don’t hurt him,” the other guard said.

The smaller gunman poured more petrol on to the truck. The man on the ground, the chain digging into his neck, felt it spill on to him. At the back of the van, a guard threw bags of cash to the gunman. They were loaded into a shopping trolley. Using a guard as a shield, the gunmen loaded the cash into their vehicle before pushing him away. As they sped off, the rear guards opened fire. They’d been lucky to escape with their lives.

But they’d also escaped with $694,000. In March 1991, the same month McSweeney escaped Boggo Road in a stolen garbage truck, the pair struck again. This time it was $142,000 and three handguns. By now, they’d carried out 12 armed robberies, netting more than $2.5 million.

Barnett isn’t sure exactly how many of these robberies ended up in the stack he was given when he returned from sick leave. He remembers a pile – banks and armoured vehicles. Always two men, one bigger than the other.

He began looking for patterns. But there wasn’t much to go on. Some of the cars were stolen. Some had been purchased using fake names.

At T.J’s Cars in Loganholme, one of the armed robbers had used the name Noel Bourke to buy a van. T.J’s had a habit of taking a photograph of their salesman shaking hands with the happy customer and displaying them on a wall of photographs.

Police who’d dropped by after the van was used in the armed robbery had noticed it. They’d asked about it. Had they taken a photograph of the man who’d bought the van? They had. But nobody could find it.

“I think there’s no doubt the reason they didn’t find it was because these offenders had gone back to the premises, stolen it and then waited several months to do the robbery so that the salesman would have trouble describing the buyer when the police came,” Barnett says.

“I thought it was worth another try. So I went back to the business and I discovered that they actually kept all of the negatives … and we were lucky enough to locate that negative.

“So, when it got developed, we had a very good side profile photograph of one of the people, or the person who bought the car. And the car had been used in this major armed robbery.

“So we had a great starting point. We finally had a photograph of someone to look for.”

Barnett hadn’t wanted to go public with the photograph. Splashing the man’s face in the newspaper may have got them a name. But it could also cost them evidence, or the element of surprise. So he did it the hard way. The long way. Burning shoe rubber, as he would describe it.

The car salesman had a vague memory of the customer saying he lived somewhere around Logan or the Gold Coast. And perhaps he’d mentioned working in the cleaning industry.

It wasn’t much, but Barnett took the photograph around to businesses, asking if anyone recognised the man. He made inquiries about “Noel Bourke” with interstate police, New Zealand authorities, prisons, pubs, betting agencies, nightclubs, restaurants, car dealers and shopping centres. He got a lot of nos. But then, one day, he got a yes. “We ended up going down to Sanctuary Cove,” Barnett says. “An inquiry we had done in the Logan area pointed us in the direction of possibly making inquiries down there.

“Fortuitously for us, only about two weeks before we arrived, a person had purchased a motorboat from the marina there and paid cash for it.

“And when I showed the photograph to the salesman at the boat brokerage, he was able to immediately recognise and identify that person and give me his real name and address.

“And that was obviously the huge breakthrough we’d been looking for.”

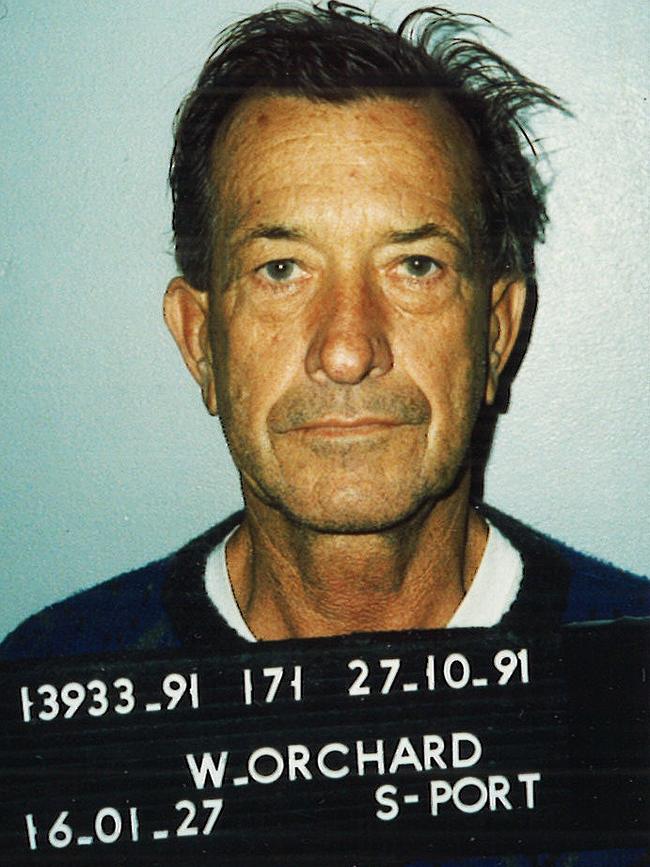

The man’s name was William Orchard. A 54-year-old with an impressive canal-front home at Runaway Bay on the Gold Coast. He’d paid $63,000 for the boat, which surveillance crews soon spotted moored outside his home – a substantial sum in 1991.

And police soon discovered the identity of his accomplice – his stepson, Garry Sullivan, a notable rugby league player.

“While we were surveilling them, we were building up a picture of both of them,” Barnett says. “It turned out … that Bill Orchard had in fact been a school cleaner quite some years beforehand. So that part of the story to the salesman was in fact true.

“(And) Garry Sullivan was a former professional footballer who had represented Australia in test matches and in the 1970 World Cup as a rugby league player.”

Surveillance teams soon discovered the men were spending a lot of time at the racetrack, where they’d drop tens of thousands of dollars on a single race. “While we were doing surveillance, it was essential that we got a positive identification on Bill Orchard as being the person who bought that car,” Barnett says.

They took the car salesman to the races and asked him to tell them if he recognised anybody. Barnett and the salesman walked around the betting ring. And there was Orchard – or Noel Bourke, as he’d called himself. The salesman picked him out immediately as the man who had bought the van.

Police watched the house from a property on the opposite side of the canal. There had already been another armed robbery – back on August 5, when two men held up a Brambles van at the Logan Village Shopping Centre. They’d been rather inventive. One of the bandits wore overalls with a breathing mask. He’d carried a weed sprayer and approached staff at the rear of a supermarket, advising them that he was from the council and would be dousing local bushland with chemicals. He’d told them to close their roller door to avoid contaminating their food. Which meant that when the Brambles van reversed into place, guards were forced to get out and approached the closed door to find out what was happening.

That’s when the bandits pounced. One of the guards had a gun held to his throat. He was told to surrender his weapon. They cuffed him and pushed him to the ground. Told him they’d kill him if he didn’t open the door of the van. They likely didn’t know it, but it was the same guard they’d robbed a year earlier at Sunnybank Hills. This was the man they’d chained by the neck and covered in fuel.

They left with $522,000 and three guns.

But by late October, they seemed to need more money. In 1991, the Queensland Police Service hadn’t the resources to have multiple surveillance teams constantly following their suspects. And on October 25, yet another Brambles van was held up – this time at Indooroopilly.

“This is it,” one of the men said to a guard, pressing a pistol into his back. They were told to lie face down on the ground. Orchard kicked one in the face, without warning. They stole a canister containing $116,000. The guard who’d been kicked in the face was ordered to his feet and used as a shield so the men could retreat.

“If he shoots, I’ll shoot you,” Orchard said to his hostage as he and Sullivan retreated to their getaway car. Barnett knew it was time to act. “We saw them return (home) in a rented car,” Barnett says. “We heard about the robbery, we knew they would have been responsible for it. So we decided to go in.”

TIME FOR A BREAKTHROUGH

Orchard’s home at Runaway Bay was protected by a 2m high fence. Police had to jump it and force their way into the house quickly. They knew there’d be guns inside.

“It was fortunate that we did, because as we restrained Orchard in the bedroom … he had hanging up in between his clothes and suits … he had a fully loaded sawn-off shotgun hanging on a strap,” Barnett says. “If he’d have got to that … we could have had some serious action.”

Between Orchard’s home and Sullivan’s, police found all 18 handguns they’d stolen from security guards. It was evidence linking them to each of the armoured car robberies.

Detectives would charge the pair with 14 armed robberies with a combined value of $3.23 million. Today that haul would be worth $6.12 million. Throughout the night and into the following morning, in an interview room at Runaway Bay Police Station, the detective who was once shot by an armed robber, sat opposite one of the most prolific he’d ever seen. “We were terrified too, I think,” Orchard told Barnett. “We never intended to hurt anyone. We’re not that bad. We might seem bad, but, all in all …”

Barnett considered the words of this man who’d jabbed at people with loaded guns, threatened them with death. “What do you think the feelings of the guards were?” he asked. “I did feel … sorry might be the word … for the fellow that was out at the front, that I was going to put the chain on,” Orchard said, omitting that he had chained the guard, by the neck.

“Would it be fair to say,” Barnett continued, “that the plan was conceived and your actions … were directed towards terrorising one or all of the guards into handing over the money?”

“Yes,” Orchard said. “We had (plans) to sort of terrorise them to give us the money. Yeah. You’d be right in saying that.”

Orchard and Sullivan were sentenced to 20 years jail with a non-parole period of 7½ years. They had little explanation to justify their reign of terror. They’d just wanted to gamble, they told a court. And besides, they’d been sick of work. Of working long hours in menial jobs for little money. So they took another way.

Detective Ross Barnett would go on to become Deputy Commissioner of the Queensland Police Service, before leaving to run the Queensland Racing Integrity Commission

Originally published as How bank teller turned cop Ross Barnett caught worst armed robbers in QLD history