Andrew Rule: How Prue Bird’s killer was caught

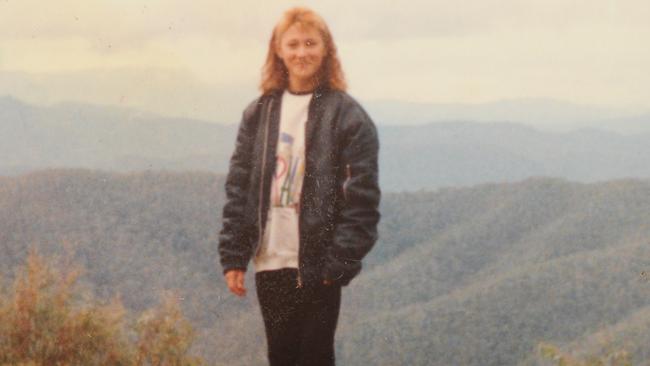

MELBOURNE teenager Prue Bird was held captive for up to a week before she was murdered, and it haunts those who loved her. But it took a convicted killer’s confession for her family to get some answers. NEW PODCAST — LISTEN NOW.

Cold Cases

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cold Cases. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THOSE who worked the case of murdered 13-year-old Melbourne girl Prue Bird say the problem is this: the system. Police need evidence a crime has been committed before they will act. But unless they act, they can’t get the evidence they need. It’s a catch-22 situation.

There are exceptions, as the Jill Meagher case shows. Following a huge public outcry, prompt and thorough police work identified Adrian Bayley within days and found Jill’s body 24 hours later.

If she had been locked in a shed alive, they would have rescued her.

That’s why Jenny Bird will always be bitter, regardless of how well individual police have treated her. Prue was held captive for up to a week before she was murdered, and it haunts those who loved her.

MORE: PART ONE: A MOTHER’S TORMENT — WHERE IS PRUE’S BODY?

PART TWO: HOW TEEN’S MURDER LINKED TO RUSSELL ST BOMBERS

Chris Jones still feels desperately sorry for Jenny. He was at Missing Persons until 1996, and stays in touch with her, despite having left the force years ago. He says she is entitled to be aggrieved — “but at the system rather than individuals”.

The system, in the 1990s, meant it was almost impossible to get telephone taps approved unless there was evidence of a crime. Even after the runaway theory faded, police had to eliminate the usual suspects: family and friends first. It was complicated by the fact the divorced Jenny had a female partner, Issie, that senior officers thought made a better suspect than the Minogues’ friends.

Issie had been home alone with Prue at the time and she conceivably had a motive — resentment of her partner’s children.

A senior officer in the crime department told a family member that child murders “happen in lesbian relationships all the time”.

By the time police were satisfied neither Jenny nor Issie had murdered Prue, the trail was cold and the real killers long gone.

Jones urged Jenny to take her two other children and move to a secret address.

She had lost her daughter, her home and was split from most of her family and friends. Between grief and sedatives, she feared she might lose her mind. The only bright spot was the kindness of police who treated her as if her loss mattered.

Her friend Christine Spalding had another premonition. “Chrissie told me that one day I’d know what happened to Prue.”

That bleak prophecy and her two younger children gave her something to live for.

EVEN monsters talk sometimes. Les Camilleri is one of the most reviled prisoners in Australian history but in the Barwon Prison protection wing where he is serving life for the Bega schoolgirl murders of 1997, he has a captive audience.

In 2009, a Barwon prisoner got a message to police that surprised them: Camilleri had boasted he was present at Prue Bird’s murder.

Soon afterwards, Camilleri told a relative by telephone he was tied to another murder, not just Bega. When the relative visited the prison he told her about Prue Bird.

Police trawled records and Camilleri’s associates looking for a link. They found he had often come from interstate to buy drugs from a dealer who “worked” with Victor Peirce.

The dealer’s name was Mark McConville. He was well known to police and linked to the most violent men in the Melbourne underworld, including some who knew the Russell Street bombers — who happened to know a criminal family living near the Birds in Glenroy.

McConville died in 2003, when his reckless drug abuse caught up with him. It was no loss — and it meant two women he had terrorised for years were no longer afraid.

One, in particular, had impressed police as a witness against one of Australia’s most prolific and evil killers, Rodney Collins, for the double murder of Ramon and Dorothy Abbey at West Heidelberg in 1987.

Collins and McConville shot Abbey in his face and cut his wife’s throat while her children cowered in the next room.

Collins at first avoided prosecution but McConville had stolen a watch from the Abbeys’ house that linked him to the scene.

He was convicted of the murders in 1989 but an appeal turned him loose in the 1990s.

McConville was the black sheep of a respectable Keilor family. One of his brothers and a cousin played AFL football but his idea of sport was torturing weaker people — especially women. By the time a pretty young woman later known as “Witness K” was caught in his web, he was a deranged, drug-dealing sadist.

By the time K gave evidence in the Abbey case against Collins in 2009 — and later in the trial of Leslie Camilleri — she was a ravaged version of the “glamour girl” who’d roamed Melbourne nightclubs with McConville in the 1990s.

When the manager of the Tunnel nightclub, Steve Boyle, caught McConville dealing drugs in the club’s toilets one night in July 1992, he dragged him out and “gave him a touch-up” then threw him out. Boyle describes McConville as “vermin — a low dog who squealed like a pig”.

Before dawn, someone nailed a pony’s head to the nightclub’s side door in Little Bourke St. Police found out years later that McConville had hacked the head off a child’s pony to stage the stunt as a grotesque act of revenge.

But that wasn’t the worst thing McConville did. By the time K gave evidence against him early this year, Det Sgt Brent Fisher and others in the homicide squad had pieced together a terrible story that had unfolded earlier in 1992.

When Mark Buttler revealed in the Herald Sun in late 2009 that Leslie Camilleri was in the frame for Prue Bird’s disappearance, it sent shockwaves through everyone who had known her. It also stirred memories.

When Prue’s friend, Melissa, by then a married mother, saw a 1990s file picture of Camilleri run with the story, she was stunned.

She had seen that man — tall, with blond curly hair and a big nose — 17 years before, in late December 1991. She had been at the Birds’ house while Jenny was away, and the tall man had knocked at the door with a bogus excuse, asking who owned the car parked in the yard.

Later, when Melissa had walked home, the man followed her in a small blue car.

“I got a sick feeling,” she recalls. She ran to a friend’s house and called her father. They told the police, who showed her pictures of cars. Nothing came of it.

Prue vanished five weeks later. Melissa did not connect it at the time, which was understandable.

Less easy to understand is that another local girl (later known as “Witness L”), saw Prue in a blue car the day she disappeared, her face and hands pressed to the window.

Memories warp and fade. The memory of K, McConville’s nightclubbing friend, recovered after he died.

No longer terrified and free of the “date rape” drug Rohypnol that McConville used to stupefy women he treated as sex slaves, she told a story that had haunted her for nearly 20 years.

She had met Camilleri with McConville in late 1991 and had driven around Glenroy with them as they looked for a girl the men planned to “knock”.

She was later able to take police to the Birds’ house in Justin Ave.

In court this year, she told of being locked in a shed in Doncaster St, Ascot Vale, with a teenage girl called Prue. The girl had told her she wanted to be a hairdresser — something no one outside the family knew.

When Jenny Bird heard that, she knew K was telling the truth.

Prue had been distressed and wanted to go home but K, addled by drugs, had warned her not to escape because she was scared of McConville. She assured Prue “We’ll be right” but that wasn’t true. The decision to save herself a beating (or worse) condemned Prue to death.

Nine days later, Camilleri was arrested in NSW on unrelated warrants. Some time that week, Prue had been killed. Camilleri admits that much. But he has reasons for not confessing who was with him and where the body is.

One reason is that the bomber, rapist, killer and jailhouse heavy, Craig Minogue, is still inside, playing the part of model prisoner. He will not want his chances of parole spoiled by Camilleri, who knows someone could get him the way they got Carl Williams if he incriminates the Minogues.

Camilleri is the only person who can tell Jenny where her girl’s remains are, and he’s not talking. Yet.

The only clue is that McConville tied women to trees in Doongala Forest in the Dandenongs. A place he called the “burial ground”.

Originally published as Andrew Rule: How Prue Bird’s killer was caught