Sussex Street Mystery: Killer butcher exposed by ‘stupid’ act in Victorian-era Sydney

A young boy found the woman’s head. The torso was nearby, but police found little else to solve the case. The killer could easily have eluded them, but for a bizarre and blatant act involving the rest of the body. WARNING: Graphic content

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For more that 20 years from 1866, Henry Shiell discharged his duties as Sydney City Coroner, delving into the lives, loves and crimes of the time.

In an era when inquests were held in the local pub, and the body would be laid out in front of the jury, death was very much an accepted part of daily life.

But some cases still shocked, and Shiell’s first murder inquiry, triggered by the finding of a woman’s severed head, was a sensation.

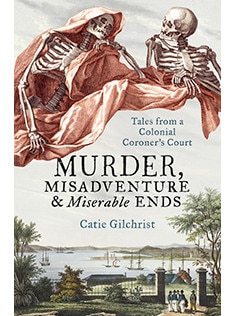

In these edited extracts from Murder, Misadventure and Miserable Ends — in which author Catie Gilchrist looks at the inquests held during Shiell’s long career — we follow that shocking discovery and the bizarre behaviour that finally pointed to the killer.

WARNING: Graphic content

ON Saturday, 15 September 1866, eleven-year-old James Kirkpatrick took his playful Newfoundland pup out for a morning walk. He opened the wooden backyard door of his home in Sussex Street, crossed the vacant land that lay immediately behind his parents’ house and headed down towards the busy working harbour. In the 1860s the area at the rear of Sussex Street, between Bathurst and Liverpool Streets, was a mishmash of factories, mills, wharves and wasteland. A stack of buildings, formerly known as Barkers Mills, housed Mr Octavius B. Ebsworth’s large and thriving tweed factory. In 1865, the factory employed seventy workers and exported its tweed to Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia and New Zealand. Ebsworth himself was a popular and benevolent employer, and regularly put on lavish social days and picnics for his workers and their families. The wasteland close to the site was used as a thoroughfare. It was also a smouldering tip for industrial scraps and nearby household refuse. As James approached the rubbish heap, his pup began to bark ‘in a very excited sort of manner’. Thinking he had perhaps found a rat, young James crouched down to take a closer look. To his horror and astonishment, the dog had not found a rat but the severed head of a dark-haired woman, whose tongue was protruding outwards. Terrified by the ghastly discovery, James quickly ran home to tell his father. William Kirkpatrick accompanied his son back to the spot to confirm the boy’s incredible claims. William then went straight to the Central Police Station on George Street.

Senior-Sergeant George Waters and a constable were soon at the scene. A few yards from the severed head they discovered the charred and decomposing remains of an armless torso. A piece of calico covered part of the chest. For the rest of the day, the police and curious locals extensively searched the rubbish heap and the surrounding wasteland but nothing further of note was discovered. Sergeant Waters placed the few ghoulish remains into a shell (akin to a body bag) and sent them to the dead house at the Benevolent Asylum, on the corner of Pitt and Devonshire Streets. Here, the medical officer of the Asylum, Dr Arthur Renwick, examined the macabre remains and estimated that the deceased had been dead for two to three weeks.

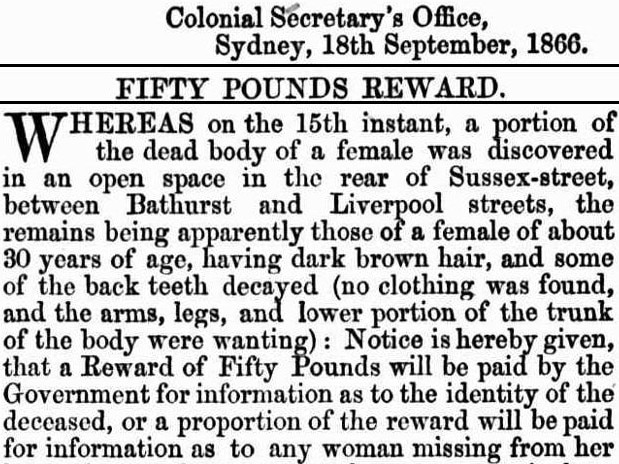

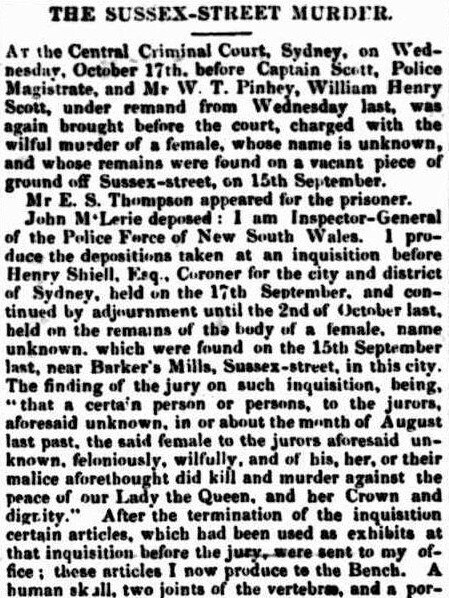

The ‘Sussex Street Mystery’, as the case became known, was Henry Shiell’s first murder as the city coroner, and the only murder inquest he held in 1866. Mr Shiell scheduled the inquest to be held at the Railway Hotel, George Street South on Monday, 17 September at 10 o’clock. Yet at this early stage the case was very much wrapped up in mystery, intrigue and speculation. Who was the woman and where was the rest of her body? The sensational news of the ‘foul deed’ and ‘fiendish act’ quickly spread across the city. Before long, ‘various and extraordinary conjectures were afloat’ in Sydney that a ‘ghastly hoax’ had been played. However, the police involved in the investigation were convinced that this was no hoax, but rather a clear case of dreadful murder by some ‘diabolical scoundrel’. Yet with little physical evidence, and no reports of missing female persons to work with, Mr Shiell adjourned the inquest until Tuesday, 25 September. A reward of fifty pounds was offered for any information leading to the detection of the guilty party or parties. But a week later, the police had made little further progress and, at the special request of Sergeant Waters, the coroner’s inquest was again postponed for another week.

When the inquest reconvened on the first Tuesday in October, much mystery remained. The police were still searching for clues, leads and missing body parts, and the only tangible certainties were the testimonies of James and William Kirkpatrick, the findings of Sergeant Waters and the professional medical evidence of Dr Renwick. As with all coronial inquests, the aim was to ascertain the probable cause of death and in this Renwick played a key role. The doctor did not have much to work with. The effects of charring and decomposition had rendered what remained of the deceased’s body extraordinarily difficult to interpret. Nonetheless Renwick’s meticulous analysis provided new and important clues as to the cause of death and also the identity of the deceased.

Renwick noted that she had a chest wound similar in appearance to a bullet wound or a piercing from a red-hot poker. There was not much left of her face, which ‘had the general appearance of having been baked or roasted’. She had had a long nose and the tip of it was burnt to a cinder. One ear was frizzled and the other was charred. Her eyes had decomposed, and her eyebrows and some teeth were missing. She had long dark hair, although much of the hair at the back of her head had gone. A blunt blow, or perhaps two blows, from a heavy instrument such as an axe or a large hammer had caused injuries to the back of her head, fracturing her skull. And her head had been removed from the neck by means of a cutting instrument.

The remains belonged to a middle-aged woman of large bones and build. The injuries to her head would have caused immediate death and they had been inflicted during her life. This, Renwick inferred, from the existence of blood over their site. The body had subsequently been deprived of its limbs and had been minutely dissected. Furthermore, the dissection had ‘unquestionably been performed by a person or persons having some acquaintance with the anatomy of the body’. It ‘exhibited a certain amount of skill, especially in the mode in which the neck had been severed’.

Dr Renwick certainly fleshed out to the inquest, and indeed to all interested Sydneyites reading the shocking newspaper reports of the coroner’s inquest, a better understanding of the deceased and the cause of her violent death. In life, she had worn twilled calico undergarments, whereas most women in Sydney wore plain calico. The manner of her death — violent and chilling on the one hand, yet precise and professional on the other — would surely hold a clue as to who her killer was. Yet the perpetrator remained unknown and, more alarmingly, was still very much at large. The jury did not take long to consider their verdict as to the cause of death:

We find that a certain person or persons to the jurors aforesaid unknown, in or about the month of August last past … feloniously, wilfully and of his or her malice aforethought did kill and murder against the peace of our Lady the Queen, her Crown and dignity.

Henry Shiell had no doubt been reminded of a similarly frightful case in London back in April 1842 when his grandfather’s Irish coachman, Daniel Good, murdered and dismembered his mistress, Jane Jones. Good was found guilty of the fiendish murder at the Old Bailey and was executed in October 1842. Following the inquest, the coroner forwarded the proceedings to Mr Plunkett, Undersecretary of the Law Department, noting that ‘the evidence of Dr Renwick left no doubt on the mind of the jury that a murder had been committed’.

Mr Shiell’s role as the city coroner in this still-unsolved case was officially complete. An unknown woman was dead, and a jury of twelve had agreed that the cause of her untimely death was murder. After the conclusion of the inquest, the coroner handed over the skull, the remaining hair and the piece of twilled calico to the police conducting the criminal investigation. For Sydney’s policemen, there was still a long way to go in solving this most sensational murder.

IN the first week of August 1866, William Scott rented a large three-storey house next to Linsley’s store at 397 Sussex Street. A few days later his wife, Annie, joined him there. She did not like the house and complained that it was too big and spooky. Mary Trevillien lived in the adjoining house. One night at the beginning of September she awoke to strange noises coming from the Scott residence. A very heavy noise, as of a body falling on the floor, shook her bedroom floor and resounded throughout the whole house. It was succeeded by two or three dull thuds, followed by a dragging or a scraping sound, as though a heavy bundle were being dragged across the floor. There were no screams.

Remember Dr Renwick’s coronial evidence? The injuries inflicted on the deceased’s head would have caused immediate death. There would have been no time to scream.

Mary had not seen Annie Scott since that evening. Mrs Ellen Craig living in the same house had also heard the strange late-night noises. She had also witnessed Annie Scott ‘sobbing violently’ a few days before. Mrs Janet Orr, a wealthy widow who owned the Sussex Street house, last saw Annie Scott on Wednesday, 5 September when Annie paid her the rent. Just a few days later, William Scott told her that Annie had left him and he no longer needed the big house. She kindly agreed to let him store some belongings in the cellar of her own house. The last time she saw William on Monday, 17 September, he told her he had lost his job and was off to the diggings. Later a heavy axe and a butcher’s sharpening steel would be found among his possessions in her cellar.

William Scott was indeed a butcher by trade, and he had lost his job. He had been working in a busy butcher’s shop in Lower George Street owned and run by Thomas Rice, who discharged him from his position on Monday, 10 September. For about a week prior to his dismissal, Scott had been acting ‘peculiar, confused and slow’ in serving customers and seemed bothered about something. Robert Sylvester and Thomas Franklin who worked in Rice’s butcher’s shop had also noticed a recent change in his demeanour. Scott carried a pistol and they had seen him taking aim at the severed heads of pigs and sheep in the yard of Rice’s shop. He also carried the poison prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide) about his person and was restless and twitchy. The week before his dismissal he had exclaimed to Robert Sylvester, ‘My God, My God! I can neither sleep, nor rest, night or day!’

There was something decidedly odd about him.

William Scott was also not afraid to show his dirty laundry in public, even when it was blood soaked and saturated with fleshy gore. Perhaps as a butcher he thought he might get away with it. In the days after Annie Scott’s death, he took blood-soaked and offensive-smelling clothes and blankets to various laundresses in the city. Strangers out on the public streets of the city had also observed his curious behaviour. Late one night in early September, he approached Edgar Weeks in George Street and asked Weeks to help him move a box. They were perfect strangers yet, despite the late hour, Weeks agreed and went with him to an unlit house on Sussex Street. In the darkness, Weeks was unable to see anything. There was a strange and dreadful smell. But it was also something he had experienced before. The smell of death after his brother and father had died.

Together they took the large tin box with an oval lid out of the house and began to walk down Sussex Street. The box was heavy and, on nearing the corner of Goulburn Street, Weeks put the box down. He was struggling with the weight, but also with his own searching imagination. The bad smell had followed them and he asked Scott what exactly was in the box. Scott replied that it was ‘only a lot of corned beef, which had gone off’. When they reached Bowman’s public house at the corner of Goulburn and Sussex streets, Weeks’s suspicions had by now spooked him. He told Scott the box was too heavy for him and he could not carry it one step further. Then he scarpered.

William Scott quickly needed another pair of hands. He popped into Bowman’s and enlisted the help of David Fitzpatrick, a young shoemaker who was in the pub drinking a shandygaff and watching customers play a game of bagatelle. They carried the box along Sussex Street as far as Liverpool Street and down near to the water. Then they carried it further, eventually leaving it in an unlit yard at the back of Kelly’s public house. Scott gave his helper a shilling as thanks and told him he would move it in the morning. The young man went home wondering what the foul smell coming from the box had been. William Scott somehow managed to upturn the heavy decomposing contents of the box into the water closet. He then went back to the Rose of Australia Inn on George Street North, where he was renting a room.

But did he really think that he was going to get away with this? Why had he enlisted helpers? Why did he empty the box into a public outhouse rather than into the vast anonymous expanse of the harbour? And then ‘with even blinder stupidity’, he kept the distinctive tin box with the oval lid, the axe and the steel, and most of Annie’s clothes and belongings. As Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Chronicle later snorted, ‘He might just as well have called a policeman.’

David Fitzpatrick eventually informed the Sydney police of his peculiar late-night incident with William Scott on Sunday, 21 October. The daily newspapers covering the sensational murder case had triggered memories of his night with a strange man and a heavy iron box that stank to high heaven some seven or eight weeks before. On receiving this new information, Senior-Sergeants Waters and Taylor went to the yard at the back of Kelly’s Walter Scott Inn, on the corner of Sussex and Bathurst Streets, and examined the water closet. Here they found a number of body parts, in all ‘some nineteen or twenty pieces’ including two legs, two arms and a pelvis. The pieces were washed, put into a shell and immediately sent to the dead house of the Benevolent Asylum. Here the dependable Dr Arthur Renwick examined yet another ghastly find.

• This is an edited extract from Murder, Misadventure & Miserable Ends by Dr Catie Gilchrist (Harper Collins).