Safe breaker Bertie Kidd’s day at the races costs bookies dear

When notorious safe breaker Bertie Kidd orchestrated a lucrative betting plunge at the races, he didn’t count on a deadly prison escape putting paid to Plan A. Plan B involved stolen diamonds.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

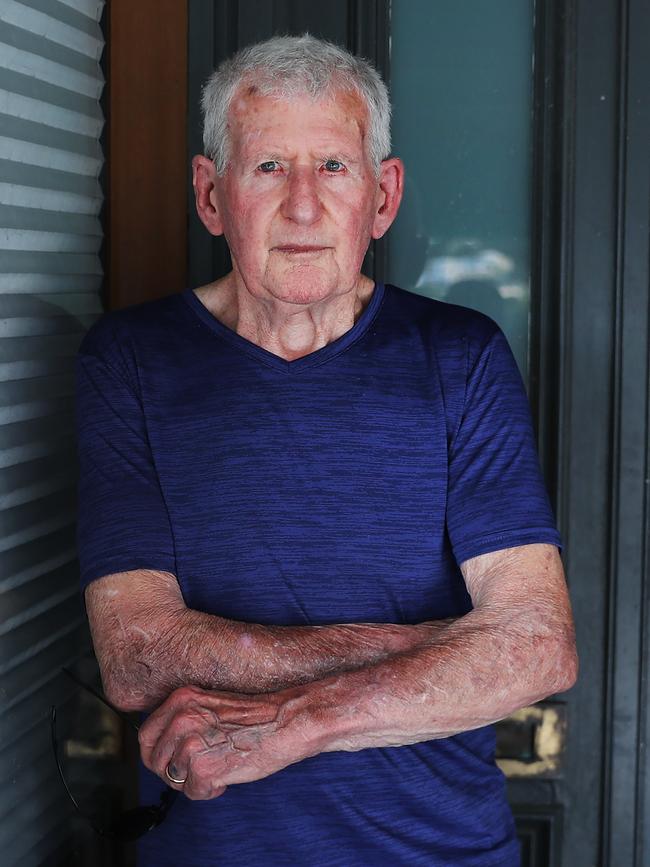

He found notoriety as a safe cracker and armed robber, but as he spills on his life of crime in a new book, Bertie Kidd reveals how stolen diamonds financed a very different money-making scheme.

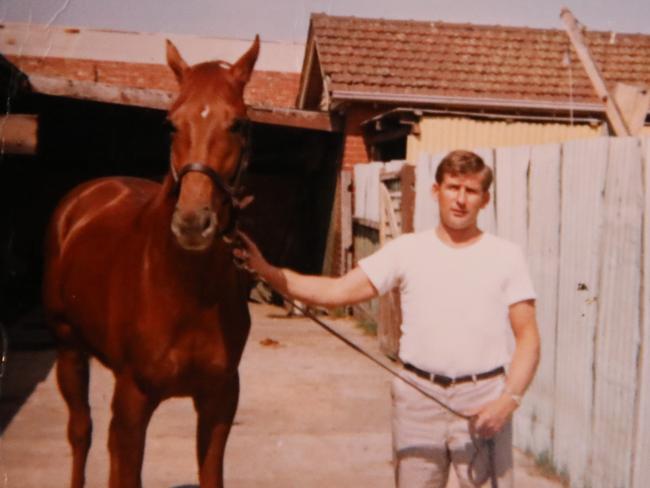

IT was early 1965 when one of my drinking buddies, a horse trainer named Peter Riley, came to me and said, “I bought you a racehorse today.” We’d discussed getting a horse some months earlier and I’d left it up to him to find something with good potential. “Well, what have you found me?” I inquired. His face was highly animated as he responded, “It’s a yearling called Why So, by a sire named Tudor Warning out of a dam named Seeta Devi, and it’ll be a winner.” “How much was it? “Twelve hundred guineas,” he said. “Okay, keep that quiet and we’ll set him for a race.” I paid him the twelve hundred guineas and told him to list the owner as Jim McDonald, (partner) Val’s dad, who loved the races.

Why So turned two on 1 August, the standardised birthday for all racehorses in the Southern Hemisphere. A few months later, Peter called and asked me to come to the track and see the horse trial. “I think you’ll be very impressed,” he said. I went to the track early one morning. Peter had organised a trial against Rod Turvey’s best two-year-old, over five furlongs. Rod was one of the best trainers in Melbourne and had a great reputation for producing champion two-year-olds.

We were all lined up at the finish line, ready for them to start. I had my binoculars trained on Why So at the barrier. It was a cold Melbourne morning and the early mist restricted my viewing. The gates opened, and the horses flew out; it took me a few minutes to focus on the big chestnut, but he looked to be keeping pace. As they came around the bend with two furlongs to go, Why So edged ahead and soon he was a length in front. My pulse was racing — there’s no better feeling than seeing your own racehorse compete well. At the finish line, Why So was a good five lengths in front. I was delighted.

Though Rod was clearly quite miffed, he walked over to me and said, “You’ve got yourself a good horse there.” Peter Riley was as happy as could be; being an ex–jumps jockey, he knew his horses. As we walked back to meet the jockey, Peter put his arm over my shoulder and with a beaming smile said, “I told you we’d win races with this one.” I gave him a hug and thanked him for the opportunity. As I approached the horse, he came straight to me, bold and daring. “There’s no fear in this boy,” I thought, and that was when I gave him the nickname “the Gaffer”.

My mind was racing as I considered my horse’s potential. We decided to put Why So out to pasture for a month and restart his training in November at Spearfelt Lodge in Caulfield. Our plan was to race him early in the New Year, when all the good horses were spelling after the spring carnival had finished. That way we’d have a wide choice of races with little strong competition.

MORE BOOK EXTRACTS:

Normally I didn’t take much interest in the Melbourne Cup, would perhaps just listen to it on the radio at the pub, but this year Peter Riley and a few of his mates invited me to attend the race. It’s always an enjoyable day out, whether you have a horse on the track or not, and this particular day was superb. My beloved Val and I dressed to the nines and enjoyed a few bubbles and beers. Peter was entertaining the girls like a true Casanova, but I was more interested in the horses. I remember seeing Bart Cummings there, who at the time was just starting out as a trainer. He had a horse named Light Fingers and the jockey was Roy Higgins. I chuckled to myself and thought, “I must bet on him. What an omen!” I headed to the bookies and managed to put £100 on at 16/1.

The bookies’ ring was an exciting place: dozens of name boards and people screaming and jostling to place their bets as the bookies changed their odds while making hand signals to each other — I made a mental note to find out what all those different signals meant.

At over two miles, the Melbourne Cup is one of the longest of any horse races. I watched intently as the horses thundered past the winning post at the end of the first lap. My heart was beating fast, just like when I was cracking a safe — the adrenaline rush felt exactly the same. As the horses ran the final lap, I began to imagine Why So running with them. But this year Light Fingers was my Why So. As they came around the turn and straightened up, the atmosphere was electric. Light Fingers was midfield, about five lengths behind the leader. Though she was finishing fast, it looked like she was not going to be able to catch up. But she came alongside the leading horse as they went past the post, and you couldn’t separate them. I had my ticket stub in my hand and I’d been squeezing it so hard it was now scrunched up in a ball. A photo finish was declared and as we waited for the result I knew I was now hooked on this sport. And Light Fingers won! I was thrilled, and Val was over the moon when she saw my ticket. We left the track that day on top of the world.

Later that month, we heard there was a crew going around various stables nobbling racehorses. They were an odd-bod group, sometimes a couple of young girls, other times two or three guys. Pretending to be animal lovers, they would approach the horses and befriend them by giving them a milk thistle. Horses love milk thistles, but these ones contained a drug that slowed them down. Invariably, the horses targeted were favourites. The drug would do its job and, come the Saturday, those favourites would lose. This was only one of a number of such ruses going on at the time. They were easily done, as back in the 1960s people were far more trusting, and security around stables was almost nonexistent. It didn’t take an Einstein to work out who might benefit from slowing horses down. If a favourite and its closest competitors could be nobbled, the bookies stood to make a fortune, particularly if they had been offering attractive odds on the favourites to seduce punters into betting on them.

Having been put on guard, I made sure my horse would be safe and secure. I would visit Why So every day at Spearfelt Lodge and often I ended up staying the night. It was around that time we decided to enter him in a Juvenile Stakes race in early January 1966. Meanwhile, Christmas was coming, always a great time for hitting safes, and I giggled with joy for a solid month anticipating my hauls. But a week before Christmas a criminal from Pentridge Prison, Ronald Ryan, escaped by shooting dead a guard. It was big news in Melbourne and every policeman was on the hunt trying to find the killer. This put my criminal exploits on hold, as you couldn’t move for law enforcement trying to find the escapee and his accomplice, Peter Walker. Every crook in town was on edge as the police carried out raid after raid on known convicts and their associates. My brother Bill was raided a few times during this period and he was a cleanskin — I think it was due to me being his brother. I kept a low profile, splitting my time between the stables, the timber yard and my home in Beaumaris, waiting for the drama to be over.

Unfortunately, I had been counting on my Christmas exploits to fund my bets on my horse. Somehow, even though I’d made vast amounts of money, it had all trickled through my fingers. It was an easy-come, easy-go lifestyle: I always knew if I needed money I could rob a safe.

Peter was very happy with Why So’s preparation and believed we would win our first race by a number of lengths. As we came close to race day, I ended up staying with my horse just about every night, and if I couldn’t do that I’d organise for somebody else to be there. To help ensure the odds would be long, we decided to put on a novice jockey who had limited rides. I’d scraped together around £6000 to bet, but if Why So was a certainty I wanted to put much more on him. I thought we would get at least 10/1. To raise more money, I decided to go to a pawn shop with my partner Val’s diamond and gold rings and see what I could get for them. When I’d first asked Val for her rings, she’d replied, “No way in heaven am I giving you my rings for a bet on a horse race!” It took me a good few days to convince her to help me out. I assured her that there was no way in hell that the pawnbroker would be keeping her rings and that even if the horse lost I would rob a safe to pay him or, if that didn’t work, rob the pawnbroker myself to get her rings back.

I went to William Tilley in Lygon Street, Carlton, which was then the biggest pawnbroker in Australia. I strode up to the counter and asked to speak to the manager and, as he approached, I laid out the eight diamond rings on a black silk scarf I owned. They gleamed and glittered against the black silk and you could immediately see the excellent quality of the stones: the diamonds were large, each one over a carat and the largest about three carats. They’d come from some of the best properties in Toorak, so I knew they were good. I’d also had them redesigned by one of Melbourne’s finest jewellers.

The manager of William Tilley shook my hand, then studied the rings closely. “These are good specimens,” he said. “The diamonds are excellent quality.” At least he was being honest — few pawnbrokers today let on how good a product is. “What do you need the money for?” he asked with a sneer. “Are you buying a block of land?”

“Don’t be silly,” I said. “It’s to bet on my racehorse.” I remember he immediately had a look in his eyes that suggested he thought the diamonds would soon be his. I said quickly, “I’m telling you now, though, you won’t be keeping them. I’ll be back in a few days to collect.” He gave me a substantial sum, a few thousand pounds, I think, enough for my bet in any case.

As the time approached, I had my spies letting me know what the odds were and where we were placed. I was camped at home. One person I wanted to keep well out of my plan was Fat Harry, an avid punter who operated from the Cricket Club Hotel in South Melbourne. He was best friends with the police consorting team, which, following Rex Greene’s retirement, was led by Albert Holmberg, and I was at war with Harry over this association. The last thing I wanted was for him to earn money off my horse. I had my bets placed around Australia. I received 15/1 initially and backed the horse down to 10/1. As soon as I had myself set, I rang Fat Harry at the Cricket Club Hotel and asked him what the odds were for Why So.

He said 15/1. I thanked him and he hung up; however, I didn’t. At the time, if you didn’t hang up, it kept the line open. I knew that Fat Harry, having got a whiff of a plunge and being an avid punter, would have hammered the bookies if he could, and that, as he was in the know, his spies would very soon be trying to ring him with a heads-up. However, with me blocking his line, he couldn’t receive or make any calls. I kept my handset muffled with a pillow, and didn’t hang up until the race was about to start.

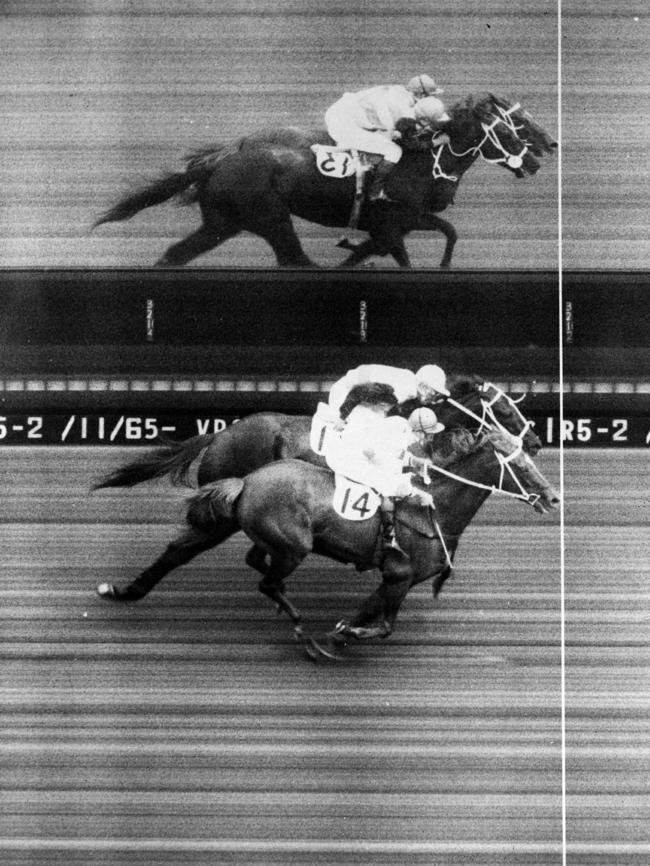

I turned the volume up on my transistor radio and listened intently as the race unfolded. Initially I didn’t even hear the name Why So, which left me concerned and wondering what was going on. But then, as they rounded the final bend, the race commentator suddenly announced that Why So had flown over the top of them all. He was stunned and said he had to check his guide. “This horse has absolutely blitzed them in the last half furlong,” he reported. “Ladies and Gentlemen, I can tell you that this is not an ordinary plunge, this is a nationwide plunge on this horse who has given them a galloping lesson today.” The bookmakers were left reeling and feeling they’d been had. I had tears in my eyes and was overjoyed. I had just pulled off a magnificent plunge and won more than £100,000, leaving me feeling euphoric. Although I was at home alone, I started celebrating by myself. I couldn’t stop laughing.

I immediately rang Fat Harry and asked him what odds Why So had started the race with. He said 5/2 then slammed the phone down. Obviously he knew from my earlier call that the odds had previously been 15/1, and it no doubt drove him crazy that he hadn’t been able to get in on the act and that I had clearly made a small fortune. That evening I had the whole crew over, including Peter Riley (and) Jim McDonald, as well as some of my good mates. Big Jim was overjoyed; leading the horse in after the race had been one of the proudest days of his life, he said, and he was the toast of Richmond. He was already as drunk as a skunk when he arrived at my place. I was now officially one of the happiest people on earth.

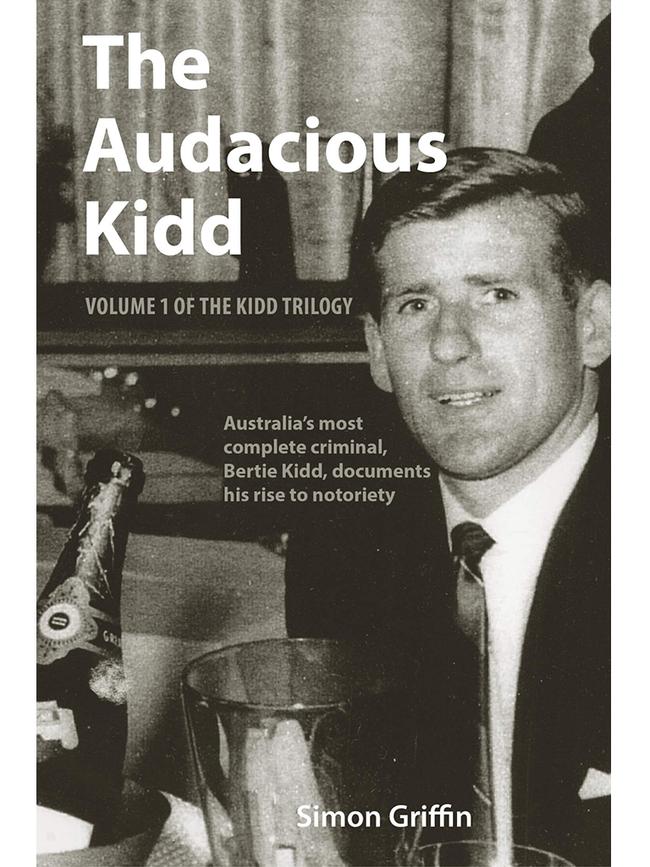

• This is an edited extract from The Audacious Kidd by Simon Griffin, published by FinPress, paperback RRP $34.95, eBook RRP $21.95.