From cop to crim: ‘How the f--- have I ended up here?’

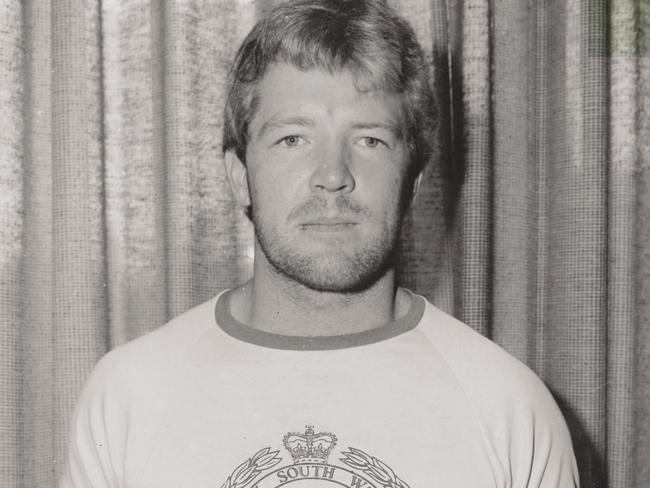

He wanted to be Police Commissioner, but when life as a cop fell apart he was a Mr Fix-It in Sydney’s underbelly, a money smuggler and a jailbird. Yet Charles Staunton reckons one title stands throughout — he’s a good bloke.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

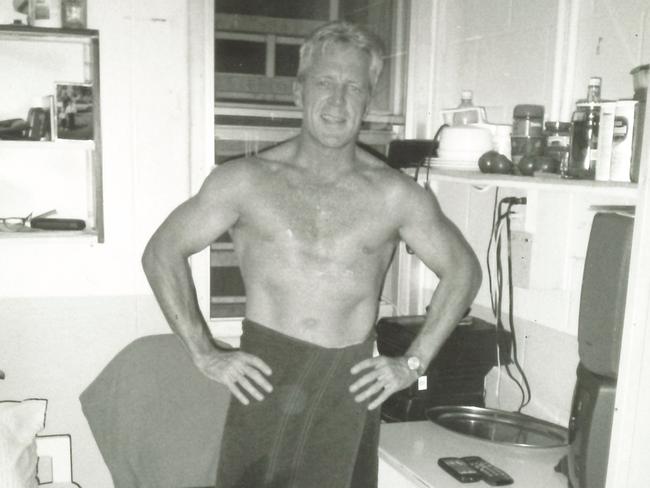

Charles Staunton lives by his own code and believes in doing the right thing — whether that’s entirely legal or not.

As a NSW cop he says he broke the law, but wasn’t bent; he went to jail rather than grass anyone up at the mid-1990s’ Royal Commission into police corruption; and after leaving the force he became a Mr Fix-It in Sydney’s underbelly, still with mates on both sides of the law.

But it was his role as a globe-trotting money smuggler for the Pacific Mariner drugs cartel — taking instructions from a man named Bram — that landed Staunton in real strife, imprisoned in a Canadian Supermax.

True Crime Australia: Baby-faced killer ‘exhausted’ from jail sex

Outback horror: Did hillbilly couple like to hunt humans?

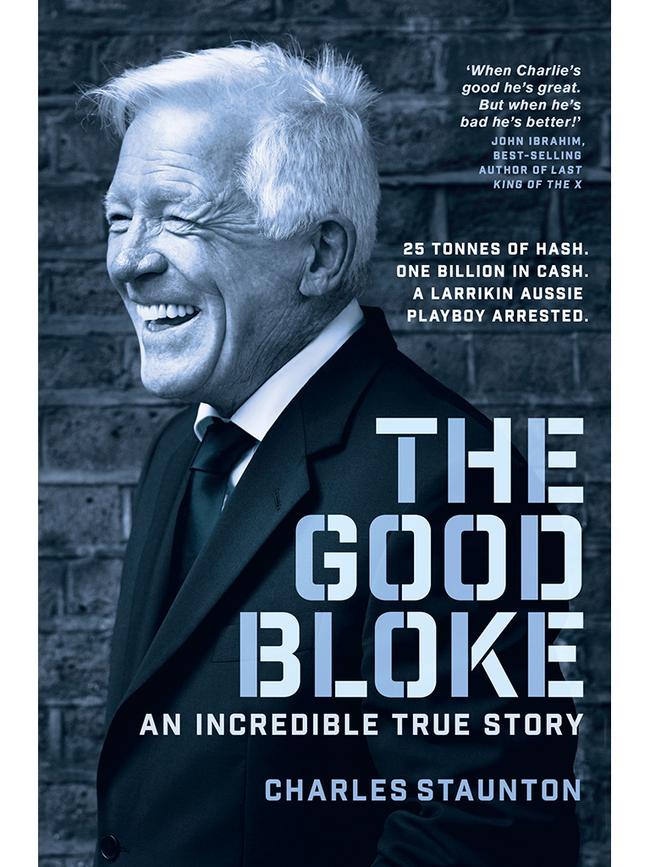

In these edited extracts from his remarkable true story, The Good Bloke, we get a taste of the moment it all went wrong, and join Staunton, dubbed The Prince, on his first big job for Bram in Montreal.

Prologue

Montreal, Canada

23 January 1997

The sun was setting over a city camouflaged in a mantle of snow. I was staying in a discreet hotel in the very funky St Denis district. The room was nothing fancy. It had a good shower and a comfortable king-size bed. In my hands I held $10,000, just a tiny fraction of the millions I had collected, counted and couriered around the globe in my time working for the Pacific Mariners Cartel.

Suddenly, there was a knock at the door. It was an all-too-familiar loud knock.

‘Police! Open up!’

S---!

I was on the second floor and the windows didn’t open wide enough to jump out. There was no escape. I had seconds to react before they forced their entry. I snapped into action.

I hid the $10,000, which consisted of only 10 notes, and an old-fashioned electric organiser with all my coded numbers under the mattress inside the nurse’s fold at the end of the bed.

I approached the door with trepidation. As I turned the knob, they stormed in like the front row of a rugby team, pistols at the ready.

They knocked me to the ground. Amid shouts and scuffling, there were knees in my back, and I was handcuffed, real tight.

A man stood in front of me with a gun pointed at my chest. His pin-prick brown eyes pierced me like a knife through butter. Peering at his face, I realised I knew him. Or at least I thought I had. A traitor right under my nose. I was filled with rage.

You lying piece of s---! Why?

‘Charles Staunton, you are under arrest for the importation of 25 tonne of hashish.’

I took a deep breath. I’d been in this situation before and had always been able to talk my way out of it. Stay calm, Charlie. Watch for mistakes. All police make them and these guys will too.

I glanced around and recognised members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), but looking closer I noticed that some of the men were wearing Department of Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) vests. A realisation dawned on me. These men are American.

Before I’d joined the Pacific Mariners Cartel, I’d done my homework. I knew the penalties for being involved in importing hash around the world. Short of the death penalty in South East Asia, America’s sentences were among the worst. A cold curl of dread spread in my chest but I pushed it down, determined to stay cool.

A young officer in front of me trembled as he shoved a Glock in my face.

‘Relax, young fellow, just relax. I’m not going anywhere,’ I drawled.

A senior officer glared down at me. ‘Oh yes, you are, Charlie,’ he sneered. ‘And it’s going to be for a very long time.’

They hauled me to my feet and marched me outside to a waiting van. I took my last breath of freedom. A blast of sharp, cold air shocked my lungs.

As they slammed the door in my face, my sons’ faces flashed through my mind.

I had a sinking feeling it was going to be a long time before I saw them again.

In the back of the police van, handcuffs digging into my wrists, a single thought bulleted through my brain: How the f--- have I ended up here?

MONTREAL WELCOMES PRINCE CHARLES

I found an apartment downtown with a secure underground car park with a lift, which I would need for the job. I rented a mobile phone and sent the number back to Bram in Amsterdam. Then almost a week later came the call I was eagerly awaiting. Bram rang and said that I was to meet a person at the Sheraton Hotel on Rene-Levesque Boulevarde, which was less than a mile from where I had rented the apartment. The meeting was set for 1pm the following day.

He then asked me to pull a note out of my pocket and read him the serial number. I did; it was a $20 Canadian bill and I read him the number. He said I was to sit in the bar adjacent to the check-in desk and to be in possession of, if not reading, a copy of Horse and Hound magazine, the oldest equestrian magazine in the United Kingdom, but freely available in any bookstore, of which Montreal had plenty.

Apprehensive, yet excited, I arrived and sat in the bar, ordered a coffee and opened the latest edition of Horse and Hound. Within minutes two very tall men arrived, both in their mid-forties. The more vocal of the pair was a redhead and the other greying, both were smartly dressed and neither looked out of place in the bar of a five-star hotel.

They approached me and said in unison, ‘Prince?’

I nodded and asked them to be seated. They both ordered a beer, and as the waiter left to get their order, they asked if I had any paperwork. I produced the $20 note and handed it over and they checked the serial number with a piece of paper from the redhead’s pocket. They nodded to each other and handed me the set of keys to a motor vehicle, and a receipt for the car park.

The redhead told me to go to the car park, take the vehicle to wherever I was going to store the contents, and that they would have a few beers and wait for me to return. I was trying to act as though I had done this a thousand times before, and desperately trying to seem professional. The truth was that I did not even know what was in the car that I now had the keys for. I was assuming that it would be money. The keys had a tag attached with the registration number of the vehicle, so I assumed it was a rented vehicle, and duly set off for the car park.

I quickly found the vehicle, which to my surprise was a small van, not a car, and it had no windows in the back. I jumped in, drove up the driveway and around the block, and was in my underground car park in less than 10 minutes.

I got out and opened the back of the van. At the rear was a small trolley and behind it were several cardboard boxes with lids that reminded me of file boxes like I had seen in legal firms.

I popped the lid of the closest box, and it was crammed full of cash, all Canadian notes. I popped the lid of two more and they were identical. All full of cash, and numbers started flying through my mind. There were twenty-three boxes, and if, as I imagined, they were all full, there was a bloody lot of money there.

I could fit four boxes on the trolley, so I loaded it and caught the lift from the car park to the second floor. When I got to the room, I popped the lids on all four boxes, and they were all full of cash in different denominations. A quick glance at the first box, and I had figured that there was roughly $400,000 in the box, and that particular box had predominantly $20 notes in it. It took me the better part of an hour to empty the van and secure the money. Well, ‘secure’ doesn’t seem quite the right term, as I just stacked the boxes in the wardrobe. One of the boxes had a money-counting machine inside and no cash.

I locked the door to the apartment and drove the van back to the Sheraton and parked it in the same spot that I had left an hour and a half earlier. I walked back to the bar where the boys were waiting. They were all smiles and asked if all was good, and I nodded and said sure.

The waiter passed the table and the redhead said, ‘Three beers.’

I sat and as cool as could be, mentioned the ice hockey, as it had appeared on a television at the end of the bar as I walked in. It started a conversation about how the Habs were about to move to a new stadium just around the corner, and that their season was reasonable, but not much to get excited over and by then the men were ordering another beer. I said that unfortunately I had work to do, and made my excuses. I stood and we shook hands, and I handed them back the keys to the van, and parted ways with the two men.

I walked down the street, then dived into subterranean Montreal and caught a few different trains to nowhere in case there was anyone on my tail, and then appeared in a different part of the city and walked back to the apartment. I called Bram.

‘Okay. I’ve received the boxes.’

‘Good. Very good. You should have a counting machine there, so start counting, and I will call you at midnight your time.’

He hung up. Eager to get started, I stopped at the famous Schwartz’s Deli, a cultural institution in Montreal on Saint-Laurant Boulevarde, and grabbed a couple of smoked salt beef sandwiches and a six-pack of Labatt blue beers. It was about five in the afternoon when I arrived back at the apartment.

I took all 23 boxes and placed them on the bed, stacked on top of each other. I set the counting machine on the desk and grabbed the first bundle from the first box, and started flicking away with pen and paper in hand. Hours later, and I mean hours later, the tally was at $23,719,000.

I sat back, turned the television on, and thought and thought and then thought again. Who the f--- gives a bloke that they have never met and don’t know 20 million f---ing dollars?

I knocked off the rest of the beers, all the time shaking my head. Bram rang at midnight on the dot.

‘So, what’s the tally? It should be $23,500,000.’

‘No, it’s …’ Before I could say, ‘it’s more’, he ranted.

‘Those sons of bitches! Those bastards! They robbed us last time.’

I had to interject. ‘Hang on, hang on — it’s $23,719,000.’

There was a pause. ‘Great! If you see the delivery guys again, tell them it was the correct weight.’

‘Sure, I thought that was a test.’

‘Charlie, you have $20 million of my money. That’s the test. Count it again, and make sure, and I will call you in the morning.’

I started the laborious task of the recount, boiled the kettle and made a coffee. Just then, a thought entered my head. I don’t know these blokes. I have well over $23,000,000 in cash. I can just … disappear. I know people all over the world.

I shook my head and promptly lost that evil thought, but I do confess it definitely crossed my mind.

As the night slowly evaporated, I noticed there was some dust in the bottom of the counting machine, I swiped my finger over it and after looking at it, it occurred to me that it wasn’t dust but cocaine. I scooped it up, racked it and had a line.

Gazing out the window, watching the first flakes of snow fall over the streets of the city, I thought it wouldn’t take nearly as long now to do the recount. The sun was up by the time I finished. The total amount had not changed by one cent. $23,719,000. And a bit of trivia: if you ever put that many notes through a cash-counting machine, the vibrations of the flickering notes will leave you with roughly a gram and half of cocaine.

• This is an edited extract from The Good Bloke by Charles Staunton, published by Pan Macmillan, available in stores from Tuesday 23 July. To pre-order or for more information visit: www.panmacmillan.com.au/9781760783037/the-good-bloke/