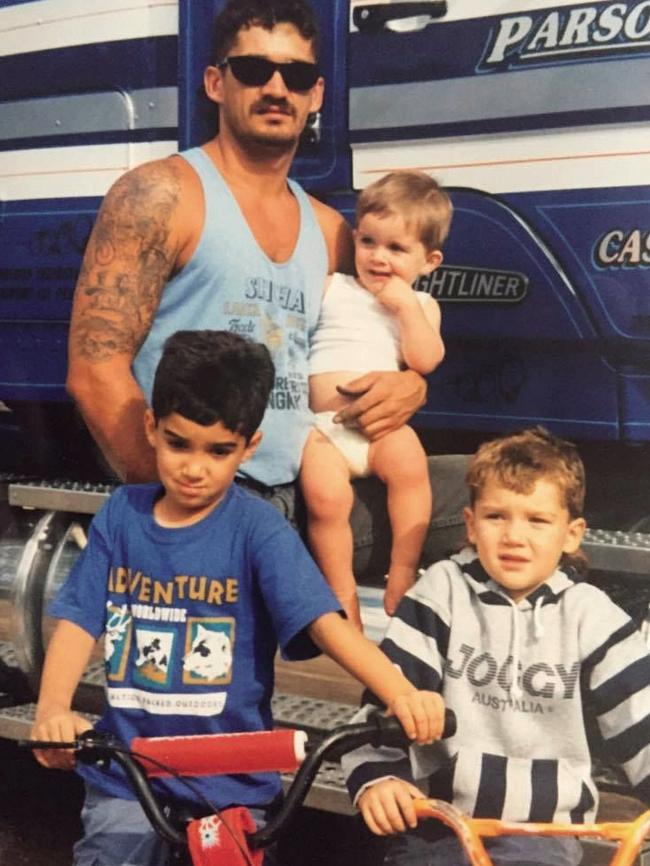

Dustin Martin’s father Shane on the day he joined Rebels bikies

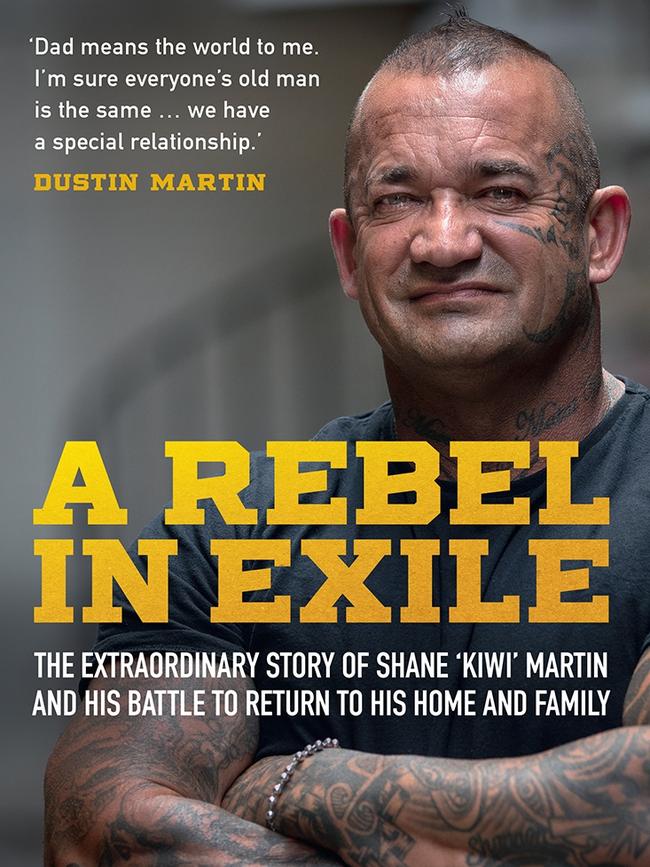

In an extract from his new book, exiled Rebel bikie Shane ‘Kiwi’ Martin — the father of AFL superstar Dustin Martin — tells how he became a member of the infamous motorcycle gang in Sydney.

The Rebel in Sydney I called was actually a guy I had met on the Tasmanian run. He let me stay with him on the Central Coast until I found my feet.

All the guys I met in the club were just as good to me. Because I was staying with him, I went on rides with the club — the Lake Munmorah chapter — and drank with the boys from time to time. They were friendly and welcoming.

I was having fun with them and soon I was part of a small group of blokes who rode with the club but weren’t members. There were four or five of us.

A couple of times someone would mention the idea of joining, and I began to roll it around in my head. Nobody put any pressure on me, but the draw was becoming stronger and stronger. Here was this group of a dozen or so guys who had this tight bond, who rode together, partied

together, and who looked out for one another. More and more, I wanted to be part of it.

The clubhouse became a home away from home. A couple or three times a week we’d be down there. The members had a meeting once a week, and then on another night we’d watch the footy and have a few beers, and on the weekend there’d be a run and then we’d end up back at the clubhouse for a party.

It was a fun place, and just good to be a part of. There was always something to do and you were surrounded by mates.

The clubhouse was an old warehouse, with a bar downstairs with club paraphernalia on the walls. Photos of the club, back patches, gifts from other chapters, stuff like that. There was a big TV and a pool table; it was a pretty good set-up. Upstairs there were rooms where you could crash out and a meeting room for members.

To join the club you need to be over twenty-one, own a big block Harley-Davidson, and go through a prospecting period — during that time you are a nominee or ‘nom’. As a nom you are part of the club, but not a full member. You don’t get to vote or attend meetings. The club’s members have to get to know you and like you enough to take you on board.

At that stage I was in my mid-thirties and I was riding around on my Heritage. So I met the requirements. One day me and the group of guys who rode with the club talked about it. We’d had a few beers and someone said, ‘Bugger it, let’s do it.’

So a few days later we walked up the stairs to the club meeting, which was on Fridays in that chapter, and said we were keen to come on board. We were then asked to leave and the members decided if they wanted us, and they did.

It was 2004, and I was officially a nominee of the Rebels Motorcycle Club.

As noms, you have to supply your own black leather vest, and they give you two small patches that go on the left side at the front. The top one is a circle with the Rebel flag and confederate skull design on it and the words REBEL POWER, and below that goes a tag with your club’s name.

Mine said Lake Munmorah. The back of your vest stays bare until you get full membership.

The nom period is basically an official trial. It lasts up to two years, or until they decide you’re ready. About a year is the norm. Before you start, you know the guys and they know you, so there shouldn’t be too many problems with personalities. But nomming is designed to put you under pressure and test your commitment. You are at the beck and call of members. If they want something done then you have to do it.

Simple things like making sure the bar is stocked, looking after members’ bikes while they’re at the pub, giving somebody a lift home when they’re drunk, fixing something that is broken at the clubhouse. You become a dogsbody. You’re everybody’s bitch for as long as it takes.

You have to spend a lot of time at the clubhouse. If there’s a party, you serve drinks and then clean up — collect glasses and wash them and mop the floors. If you’re not behind the bar you might be on the door, or on the gate as security. You have to do some long hours and it’s a big commitment. And that’s the test. Are you prepared to show you want the patch? What is earned easily is easily thrown away.

It’s a period when members find out if you are right for the club, but equally a time when the nom finds out if the club is right for him. You have to be able to fit into the culture. You have to show that you can handle yourself and keep good form, and that you won’t be an embarrassment to the club. There are some things you absolutely have to tick off though: you need to go on a national run and attend a bike show. This is so that you can meet a wider

group of members other than just the guys in your chapter.

All chapters do things a bit differently, but those are staples pretty much anywhere.

A lot of people will tell you it’s bloody hard being a nom. As it happens, I enjoyed it. I had always been a worker, so long hours didn’t bother me and I loved the club. It gave me as much as I was giving it. Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t have done it if I hadn’t wanted my

colours, but I didn’t mind nomming at all.

One meeting night — which is called ‘church’ — us noms were downstairs in the clubhouse just stocking the bar and generally mucking about. Members don’t drink before meetings, so we were mostly just waiting for it to finish. The members came in one by one and filed upstairs

for their eight o’clock meeting. A while later, a bark came from upstairs. “Kiwi, come up here!”

At first I thought they just wanted some beer or something, but it became clear it was a bit more than that. The members were sitting at a long table with the president at the head. Everyone was looking at me. “What in the f*ck,” the prez bellowed, “were you doing

down at the pub on Friday night telling everyone you’re a hard c*nt?”

I stuttered a bit because I was racking my brain, trying to think what I’d done. “What … what are you talking about?” I finally managed.

He leaned over the table and pointed a finger at me.

“You f*cking know what you did, Kiwi, you f*cker. You’re getting another three months as a nom.”

The colour must have drained out of my face. I wanted to defend myself but noms don’t get to argue back, especially not with the president.

Then someone began to splutter, and a second later everybody was roaring with laughter.

The president’s face opened up into a toothy smile and he said, “Come here, brother. As of tonight you’re a member of the Rebels.”

He came out from behind the table and gave me a big bear hug. One by one all of the other members did the same. I was handed a plastic bag with the four parts of the back patch and the rest of the front in it. I had my colours.

I was in.

A Rebel In Exile by Jarrod Gilbert and Shane Martin; Hardie Grant Books; RRP $29.99