Secret life of our worst women inmates

THEY are the women too dangerous to be left in the main prison population. Now one woman who served time with them reveals what really happens in maximum security — and the letters the killers sent her.

Behind the Scenes

Don't miss out on the headlines from Behind the Scenes. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FOUR lonely cells stand side-by-side at the end of a long white-walled corridor.

This is a maximum security segregation unit inside one of Australia’s toughest women’s prisons — a holding space for inmates deemed either too dangerous or to at risk to be left with the mainstream prison population.

More True Crime: The Bank robber convicted by his own arrogance

Picture special: Policing in the ’70s - the crimes, the tech, the fashion

Behind the heavy steel doors sit four of Australia’s most infamous female criminals — serial baby killer Kathleen Folbigg, NSW’s most feared prisoner Rebecca Butterfield, Belinda Van Krevel — who ordered her father’s murder and would later go on to stab her boyfriend — and Roxanne Dargaville, doing time for a string of offences from armed robbery to assault and fraud.

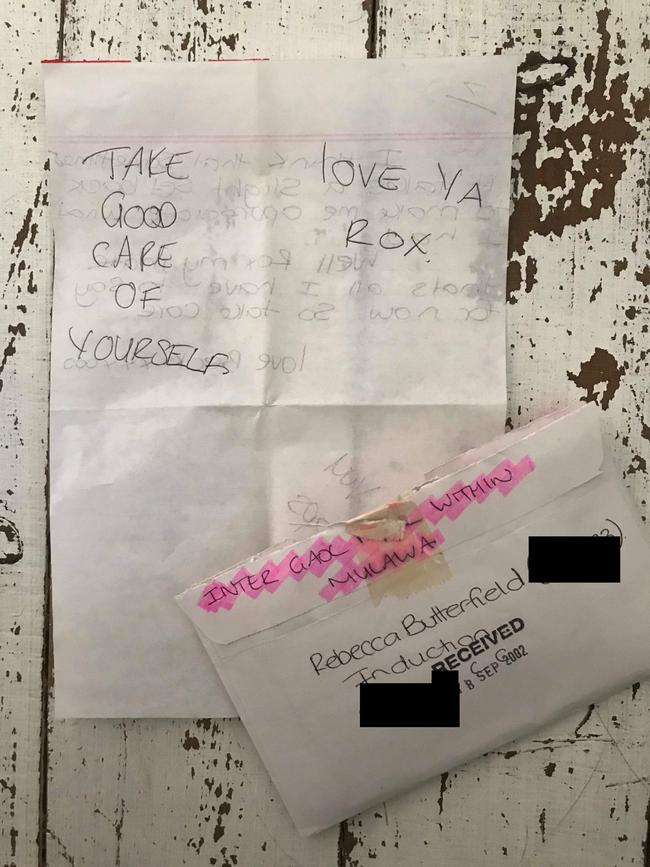

In an exclusive interview with True Crime Australia, Dargaville has agreed to lift the lid on what really goes on inside a women’s maximum security prison and the secrets shared between the infamous inmates through letters, passed to one another through “inter-jail mail”.

It’s in these never-seen-before notes, in some cases just scrawls on torn pad sheets with single musings, that the infamous criminals express their innermost thoughts and the forces that drive them.

“I seem to be hurting the officers that do the most things for me. I do regret throwing the hot water on them but sometimes the thought just enters my head and no matter how hard I try to forget about it, it doesn’t work,” writes Butterfield in one note.

Male and female inmates at the different prisons would write to one another and forge inter-jail penmail relationships. Dargaville claims in some instances this leads to affairs with guards which was “common” and sex behind bars was “easy”.

This is a world very different to the outside, where allegiances are determined by race and genre of crime. There are rules in here, and a hierarchy.

It’s a place where violent spats between women can erupt over something as simple as a glass of milk and affairs with guards are “common”. Each day offers an unknown mix of assault, self-mutilation and violent attacks on officers.

If you want to survive, friendship and loyalty is paramount.

“The first thing when you walk through the doors is: Am I going to get bashed? Am I going to get raped? Am I going to get assaulted?” says Dargaville, who was first sent to prison as a minor for assault and theft.

“You watch programs like Prisoner and Orange Is the New Black and some parts of it give a true representation of what prison life is like and some of it is so far from the truth.”

For Dargaville, Butterfield, Folbigg and Van Krevel, who have been separated from the main prison population as the “problem children” of Mulawa, now renamed Silverwater Women’s Correctional Centre, there is little opportunity for human contact.

Almost the entire day, bar an hour, is spent locked in their cells. These are women deemed too dangerous, either to others or themselves, to be left to wander the jail corridors for long.

But they can hear each other and their voices singing out from the cells, as they discuss everything from appeals they might have coming up, to how they could get their hands on contraband, to the people they miss most on the outside.

“There was only four cells there. There was Kathleen Folbigg, Rebecca (Butterfield), me, and another girl (Belinda Van Krevel). We were permanents in there. We were the problem children,” says Dargaville, 52, who was released in 2002 and who has been able to turn her life around and never return to prison.

“We used to ask the other inmates for things. I would ask them for razors to cut myself and Rebecca would ask for razors and matches.”

In the segregation cells, the women have a steel toilet, a metal bed, a desk area and a television, usually black-and-white, but inmates who saved up could pay extra for colour.

The door has a perspex window, approximately 30 centimetres high, which looks out to the empty corridor and there’s a small gap between the bottom of the door and the floor.

“We used to do things like make toast and kick it under the door and then we had a trick for boiling water, you use a power point,” says Dargaville.

“We had some f---ing ingenious prisoners in there. When we ran out of matches we used to get toilet paper, and you roll it up into a long wick, you roll it, you can plait it, and you light the bottom of it and it stays alight for 12 hours — you can light your cigarettes. It worked,” she shrugs.

“You stay in the cell all day and you get an hour for exercise. But Rebecca and I, we were like sweepers,” says Dargaville, referencing the term given to women granted the privilege of cleaning the jail.

“So we were allowed out together ‘cos they trusted us together, god knows why … but they did.

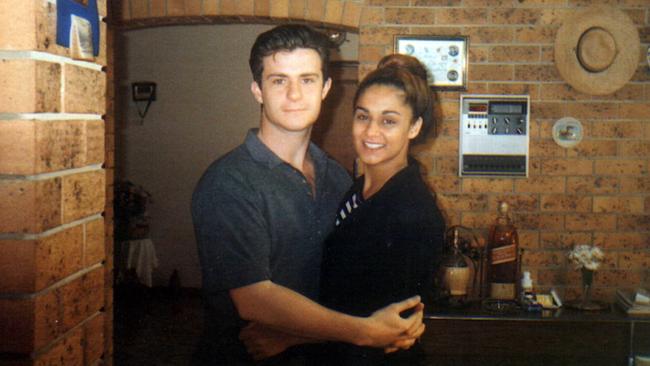

“Rebecca and I struck up a good friendship, like she was someone I could relate to. She’d suffered abuse too, we just got on. We were able to confide in each other about certain things that had happened to us,” says Dargaville, who in 1996 released autobiography Roxanne: My Extraordinary Life about her institutionalisation from a young age and the physical, emotional and sexual abuse she suffered growing up.

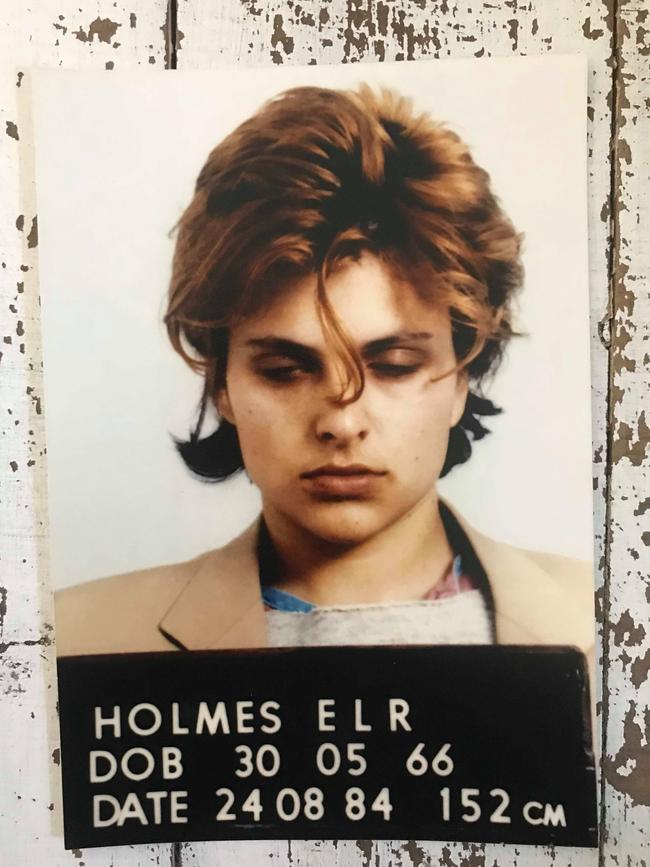

Butterfield was originally convicted of the relatively minor crimes of malicious damage, drug offences and unlawful entry in 1996.

But the violent acts Butterfield has committed inside have kept her locked up, earning her the reputation of NSW most violent prisoner.

In 2003, Butterfield murdered prisoner Bluce Lim Ward by stabbing the Filipino businesswoman 33 times in an unprovoked attack fellow prisoners described as a real-life “fatal attraction”.

Dargaville was with Butterfield just hours before the vicious murder.

“She was OK,” recalls Dargaville, who had been released from prison at the time but returned to visit her good friend at Emu Plains Correctional Centre. “She just seemed like Rebecca … but you never know what’s going on inside of somebody.”

Butterfield is the daughter of a policeman and was raised in a well-respected country family.

Dargaville remembers her as a “sweet young girl”. “Like me, she was really vulnerable,” she says.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

During her incarceration Butterfield has self-mutilated and attacked staff so many times, Corrective Services applied successfully to have her kept inside five years beyond the end of her sentence, on the grounds that she was considered too likely to reoffend if released.

Now in her early forties, Butterfield is known to self-harm in an attempt to lure officers into her cell so she can attack them, her lengthy file bearing a chilling warning: “Exercise caution on all external escorts. Butterfield is able to remove handcuffs,” it reads.

In vicious self-harming episodes, she has slit her own throat, banged her head against a wall over a hundred times causing her skull to split, and tried to hang herself.

“Rebecca was doing things like swallowing batteries, swallowing glass, inserting metal under her skin. She was taken to hospital so many times, hundreds of times,” says Dargaville.

“I was in Mulawa with Rebecca the day she set herself on fire. I think I was having exercise or something in the common area. She lit her clothing on fire. I think she set the blanket on fire and she suffered extreme third degree burns to all of her legs.

“I mean she burnt herself badly and then she was taken out where she spent quite a while in hospital getting skin grafts,” says Dargaville.

Guards who have come to her rescue have had their face sliced open with makeshift weapons, been showered in cups of urine and boiling water and a pregnant nurse who was treating her copped a kick to the stomach.

“I won’t be able to go outside,” she writes. “If I come out of my cell I have to have a restraining belt on. That’s because of the assaults I did on the officers.”

But at one time, Butterfield was a girl with a future.

“She loved horses,” says Dargaville. “Rebecca had dreams of becoming a vet nurse. She always wanted to work with animals and I was trying to encourage her when she got out to do a TAFE course. She was nearly due, like in a month, for her release and then in a moment of madness Rebecca asked for her medication (anti-psychotics).

“So she went back, picked up a kitchen knife from inside one of the houses — ‘cos Emu Plains is like a compound with different houses — and then stabbed that girl (Bluce Lime) to death in a fit of whatever it was, rage.

“Like me, she would go off in a heartbeat,” says Dargaville.

“She’d go from zero-to-hero. She’d go right off the Richter-scale, unable to cope with whatever it was. For me, it was lot of voices in my head and for Rebecca — she used to go through the same thing, with a lot of explosive anger. She heard voices too, Rebecca. She struggled.”

Butterfield received a 12-year sentence for the crime; her current release date is November, 2020.

Kathleen Folbigg was the prisoner kept furthest from the rest of the inmates in the cell block of four.

In 2003, Folbigg was sentenced to 40 years in jail — with a non-parole period of 30 years — for the murder of her three infant children, however this was reduced to a 30-year sentence on appeal.

The mother from Newcastle, NSW, was also convicted of the manslaughter of a fourth child.

When Dargaville got to know her, she was on remand but she refused to tell the other “girls” what she was in for. But once the guards spread the word, Folbigg was in trouble.

“The entire time she was in isolation because people wanted to kill her ‘cos she’s a child killer,” says Dargaville.

“Kathleen would talk s---. She was well hated in the jail, very well hated … I still think she’s in isolation.

“She was referred to as a “kid killer” but she seemed so normal that was the thing. If you’d just met her you wouldn’t think she was capable of doing such horrendous things.

“Anyone that has a crime like that ends up being segregated because there’s a system of hierarchy with the inmates where they dole out their own justice. People tried all sorts of stuff, spitting in her food, threatening her, saying she’s going to get killed.

But that’s just general stuff, the everyday stuff. She didn’t want to touch to food because people did spit in it,” says Dargaville.

Folbigg has always fiercely proclaimed her innocence and currently has a support group of friends and lawyers at the Newcastle Legal Centre campaigning for a retrial, their claims supported by academic lawyer, Emma Cunliffe, who argues in her book Murder, Medicine and Motherhood, there is no scientific evidence to prove Folbigg murdered her babies.

Dargaville still remembers Folbigg’s certainty she was going to be let off ahead of her trial — but she was very, very wrong.

For a while, Dargaville was considered one of NSW top ten most dangerous prisoners — so dangerous, authorities had a law passed that would allow her to be the only female kept in leg chains.

Prison staff struggled to contain her and in two incidents she took staff members hostage. The head of Long Bay prison, Pat Aboud, still vividly recalls the 45 minutes he spent negotiating with her, as she held a steak knife to a female case worker’s throats — an incident that earned him a bravery award.

Dargaville takes responsibility for her actions but wants it known she believes her fierceness stemmed from the combination of a severe, undiagnosed mental illness — she has since been diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder — years of physical and sexual abuse during her childhood and her institutionalisation from a young age, where she received an education in criminality from other inmates.

Despite her reputation, Dargaville was terrified of the other prisoners. She recalls the heart-stopping moment she met notorious killer Katherine Knight, the first Australian woman to be sentenced to life without parole.

The two women were being held side-by-side in “safe cells”. These are special holding cells to constrain violent prisoners, who are dressed in white overalls and padlocked to the wall.

“I was in the safe cell, I’d been in there for weeks, and she came in into the cell next door,” says Dargaville.

“I said, ‘Hi.’ She said, ‘Hi.’

“She started talking to me. She said, ‘What’s your name?’

“I said, ‘Roxy.’

‘What are you here for? Why are you in the cell?’ Knight asked.

‘Because I’ve been cutting myself,’ Dargaville told.

“And this lady seemed fine, she seemed like a normal person … so I said, ‘Why are you here?’”

Knight didn’t miss a beat.

“Killed my husband, chopped him up,” she said.

Dargaville’s eyes widened as she stared into the space before her.

‘F---,’ she whispered under her breath.

However, Knight’s description paled in comparison to her actual crime.

In February, 2000, Knight stabbed her partner, John Price to death at their home in Scone, NSW. Several hours after his death, she skinned the father-of-three and hung his pelt from a metal hook in her living room doorway — but she wasn’t done yet.

Next, Knight decapitated Price and cooked parts of his body, which she served to his children with a side dish of baked potato, pumpkin, beetroot and gravy.

His head was later found still warm, in a pot with vegetables.

“She was actually a really nice person,” says Dargaville.

“I got to know her well at Mulawa and she said she finally feels at home. She feels a sense of peace over her life, she feels more peace in there than she feels out here.

“She used to walk around Mulawa with other inmates, she’s in the system now.”

Not everyone was as “nice” as Katherine Knight.

Belinda Van Krevel is one prisoner Dargaville describes as “a very evil girl, very cold”.

As one of the four women in Mulawa’s segregation unit, Van Krevel would spend her days talking about her role masterminding her father’s murder.

In August 2000, Van Krevel asked her boyfriend, Keith Schreiber, to kill her father, Jack Van Krevel.

Schreiber hacked Jack to death with a tomahawk in his Albion Park home. Belinda, just 19 at the time, lay in bed in the next room, listening to the long attack and her father’s cries of mercy.

“Hello my 58,” writes Belinda Van Krevel, using the rhyming slang for “mate”.

“There hasn’t been much going on here. Just the same old routine nothing exciting but I’ve met a few guys and I’ve actually got a boyfriend he’s at Goulburn (sic) Jail I’ve been with him for 6ix months and I’ve got photos of him,” she adds.

Dargaville describes Van Krevel, who often boasted about her crimes and those of her serial killer brother, Mark Valera, as “a complex creature”, “a very evil girl, very cold”.

In 1998, Valera was convicted of the gruesome murders of David O’Hearn and Frank Arkell and became the youngest man to be sentenced to Supermax, Australia’s maximum security prison.

“She was proud, she was proud of what her brother had done. She was a very complex creature. I think having the tag of murderer was status,” says Dargaville.

Anu Singh was another inmate who seemed to have an equally tenuous grasp of morality and the concept of remorse.

In 1997, Singh — a law student at the Australian National University — in Canberra, organised a dinner party so she could murder her boyfriend, Joe Cinque. Singh laced his coffee with sedative, Rohypnol, before injecting him with a lethal dose of heroin. She was sentenced to 10 years for manslaughter but released after three.

“I’ve never heard her say she was sorry for what she did to Joe,” says Dargaville, who built a close friendship with Singh during their years in Mulawa and Emu Plains.

She describes Singh as a “narcissist” who even in prison was obsessed with her own appearance and constantly exercised, terrified of gaining weight.

Despite her close friendships while in jail, some of which continued for years on the outside, Dargaville chooses to dissociate herself from the prison system. She is not proud of her criminal past and takes full responsibility for her actions but stresses that her crimes, like the initial crimes of her cellmates Belinda Van Krevel and Rebecca Butterfield, could have been prevented with better mental health care and treatment for the abuse they suffered as children.

“You can’t take someone like me with what I’ve experienced and place me into a normal community and expect me function as a normal person,” says Dargaville.

“Not all people who go to prison are bad, that’s the thing, you’ve got to separate the wheat from the chaff. People deserve the opportunity who go to prison they should have an opportunity to heal their lives.”