What you need to know about North Korea’s nuclear bomb test as more questions are raised

AFTER North Korea said it carried out a nuclear bomb test, an Aussie expert weighs in to answer questions about its military power.

Science

Don't miss out on the headlines from Science. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AFTER North Korea said it carried out a “successful” hydrogen bomb test, more questions than answers remain about the rogue nation’s military power.

The latest nuclear test, its fourth nuclear blast, has sent shock waves through the region with leader Kimg Jong-Un’s latest bout of sabre rattling.

“Let the world look up to the strong, self-reliant nuclear-armed state,” Kim wrote in what North Korean state TV displayed as a handwritten note.

“Let’s begin the year of 2016 ... with the thrilling sound of our first hydrogen bomb explosion, so that the whole world will look up to our socialist, nuclear-armed republic and the great Workers’ Party of Korea!”.

MORE: How the North Korea nuclear test unfolded

Here are five questions about North Korea’s nuclear program and its impact on regional diplomacy and security:

Q: Can North Korea’s claim be believed?

A. Experts broadly agree that the country probably carried out some kind of nuclear explosion but are sceptical over the “hydrogen” assertion.

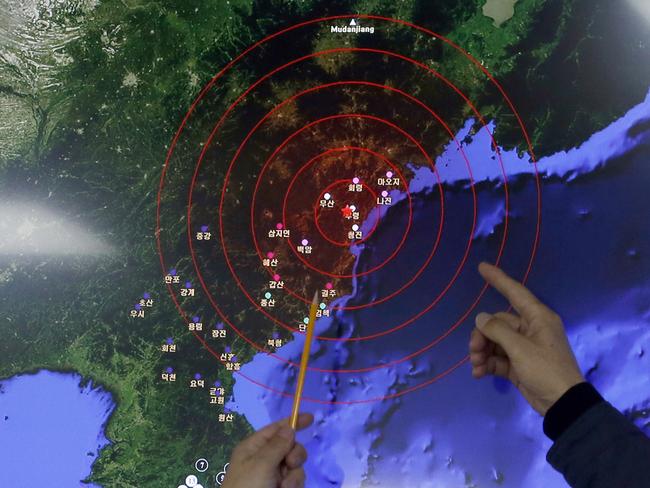

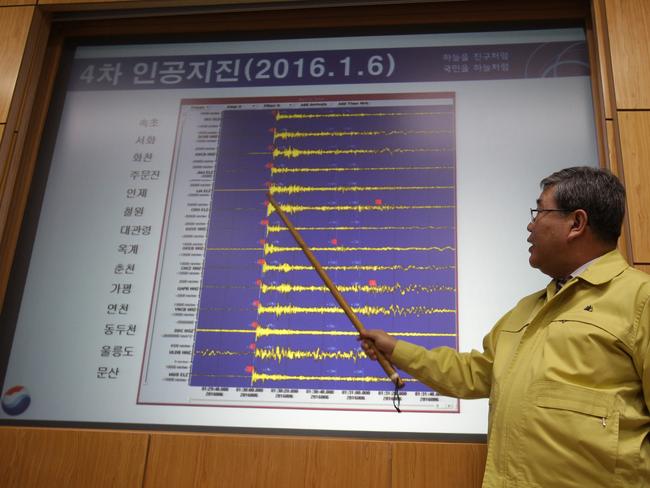

The first clue that something happened came with reports of a 5.1 magnitude earthquake near the North’s nuclear test facility. North Korean state television later announced that it was a hydrogen bomb test.

But Australian nuclear policy and arms control specialist Crispin Rovere said that “the seismic data that’s been received indicates that the explosion is probably significantly below what one would expect from an H-bomb test”.

“So initially it seems to be that they’ve successfully conducted a nuclear test but unsuccessfully completed the second-stage hydrogen explosion.”

South Korean intelligence officials and several analysts however also questioned whether the explosion was indeed a full-fledged test of a hydrogen device.

The device had a yield of about six kilotonnes, according to the office of a South Korean MP on the parliamentary intelligence committee — roughly the same size as the North’s last test, which was equivalent to 6-7 kilotonnes of TNT.

“Given the scale, it is hard to believe this is a real hydrogen bomb,” said Yang Uk, a senior research fellow at the Korea Defence and Security Forum.

“They could have tested some middle stage kind (of device) between an A-bomb and H-bomb, but unless they come up with any clear evidence, it is difficult to trust their claim.” The United States Geological Survey reported a 5.1 magnitude quake that South Korea said was 49km from the Punggye-ri site where the North has conducted nuclear tests in the past.

North Korea’s last test of an atomic device, in 2013, also registered at 5.1 on the USGS scale.

Q. What does the new test mean in terms of North Korea’s nuclear development?

A. The test nevertheless may mark an advance of North Korea’s nuclear technology. The claim of miniaturising, which would allow the device to be adapted as a weapon and placed on a missile, would also pose a new threat to the United States and its regional allies, Japan and South Korea.

Despite doubts over the claim it was a hydrogen bomb, it still demonstrates the country’s commitment to carrying on with its nuclear program. It comes after three previous nuclear explosions between 2006 and 2013 and a boast last year the regimen had developed a hydrogen bomb. North Korea is continuing with their test program without regard to what the world thinks, Christopher Hill, former US chief negotiator to the six-party talks aimed at the North’s denuclearisation, told the BBC. “We have a big problem regardless of how large the explosion was today,” Hill said.

Q. What is an ‘H’ bomb?

A. The hydrogen, or thermonuclear bomb works on the principle of fusion of two nuclei, and generates temperatures similar to those found at the sun’s core. When an H-bomb is detonated, chemical, nuclear and thermonuclear explosions succeed each other within milliseconds. The nuclear explosion triggers a huge increase in temperature that in turn provokes the nuclear fusion. The first US test of an H-bomb was on November 1, 1952 in the Marshall Islands, a chain in the Pacific Ocean.

A year later the Soviet Union tested its own H-bomb, and the largest blast to date took place on October 30, 1961, when the Soviet “Tsar Bomba” exploded in the Arctic with a force of 57 megatons. No H-bomb has been used in a conflict so far, but the world’s nuclear arsenals are comprised for the most part of such weapons.

“Most of the thermonuclear warheads in service today have so-called ‘dial-a-yield’ options that allow for low explosive yields (less than 10 kilotons) with a considerable fraction of that yield derived from fusion reactions, that effectively make them enhanced radiation warheads,” notes Shannon Kile of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

Q. What does the test mean for international relations and diplomacy in Northeast Asia?

A. Most of all, it will mark a new low point in relations between North Korea and neighbouring China, which has been the country’s main diplomatic supporter for decades.

Beijing’s patience has run increasingly thin as it strongly opposes Pyongyang’s nuclear development and sees it as a factor for instability on the Korean peninsula, where it has strong trade relations with North Korean rival South Korea.

“Beijing will face increased pressure both domestically and internationally to punish and rein in Kim Jong-un and to ultimately force Pyongyang to give up its nuclear weapons,” said Yanmei Xie, International Crisis Group’s Senior Analyst of Northeast Asia based in Beijing.

“But there is likely to be a repeat of the worn playbook of denunciation, tightening of sanctions, and calling for resurrection of the six party talks.” Relations with South Korea are also likely to suffer, with attempts to improve dialogue and reduce tensions along their heavily fortified border to come under renewed pressure. Japan, a target of previous North Korean threats, is likely to increase its guard.

Q. Why now?

A. Kim, who has carried out numerous purges of senior officials since coming to power after the death of his father Kim Jong-il in December 2011, is believed to constantly need to solidify his power base and demonstrate achievements even greater than those of his father and grandfather, North Korea’s founder Kim Il-Sung.

The announcement also comes just two days before his January 8 birthday and also in advance of an expected congress of North Korea’s ruling Workers’ Party — the first such gathering in 35 years.

“The purpose of this is firstly to display to the world that it has acquired a new technology as to the nuclear weapons program,” said Toshimitsu Shigemura, a professor at Waseda University in Tokyo and an expert on North Korea.

“Secondly, with the (claimed) development of hydrogen nuclear weapons, Kim Jong-un now has a ‘great achievement’ that even Kim Il-Sung or Kim Jong-il could not realise.”

Q. What’s next?

A. Past North Korean nuclear and ballistic missile tests have been followed by condemnatory United Nations Security Council resolutions and additional sanctions.

Diplomats said that the UN Security Council is to hold an emergency meeting on North Korea on Wednesday.

“This clearly violates UN Security Council resolutions and is a grave challenge against international efforts for non-proliferation,” said Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Originally published as What you need to know about North Korea’s nuclear bomb test as more questions are raised