Image of Tiananmen Square ‘Tank Man’ poignantly sums up Australia’s online censorship debate

As politicians rally for “social decency” and wage a mudslinging war with Elon Musk, a far greater issue threatens to slip under the radar.

Social

Don't miss out on the headlines from Social. Followed categories will be added to My News.

OPINION

In the wake of the horrific week that saw two separate knife attacks unfold in Sydney, Australia’s politicians have scrambled to appear as if they’re doing something.

The proliferation of violent videos, both of the Bondi stabbing perpetrator and the teenage knife-wielder at a church in Western Sydney, sparked a moral panic that felt fresh out of Reagan’s America.

Nobody is denying the severity of the unspeakably disgusting acts that have causing pain and suffering. But the knee-jerk reaction from both wings of Australian politics has holes that can’t be ignored.

At face value, the 2021 Online Safety Act is a necessary measure that grants the eSafety Commissioner the power demand the removal of “class 1 material”, which includes violent crime, child sex offences, or other “revolting or abhorrent phenomena [that] offend against the standards of morality, decency and propriety generally accepted by reasonable adults”.

But who really gets to decide “decency accepted by reasonable adults”?

How many of us actually assume “reasonable adults” are running the country?

What was conceived as something to benefit the public could quickly grant future governments the power to perpetually control what we can and can’t see online, with the “offensive” material ultimately judged by a single taxpayer-funded official.

The extremes are clear, but the grey area is bigger than Mick Jagger’s ego.

Australia’s eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant, who is paid $444,983 per year, made her views crystal clear in 2022 while sitting on a panel at the World Economic Forum.

She spoke of the need to “recalibrate a whole range of human rights”, attracting heavy criticism.

She started off well but took a tumble in the second sentence.

“We are finding ourselves in a place where there’s increasing polarisation everywhere and everything feels binary when it doesn’t need to be,” she said.

“So I think we’re going to have to think about a recalibration of a whole range of human rights that are playing out online – from freedom of speech to the freedom to be free from online violence.”

Elon Musk’s X is at risk of being charged more than $782,500 per day for refusing to take down videos from this month’s tragic events in Sydney, prompting a mudslinging match between Aussie politicians and those who believe they are venturing far beyond their jurisdiction.

It goes without saying the victims deserve their respect, and their families should be protected and given every available service to recover from the unspeakably tragic events.

The Prime Minister claims it is merely in the name of “social decency” — but judging by the relentless backlash he’s faced online, it appears that has fallen flat.

The philosophy behind online censorship has and will continue to be defended as a means to protect Australians, but if you scratch the surface you begin to see distinct parallels with nations who have some pretty horrendous human rights track records.

The issue, which is sparking a ferocious response from thousands, is that anyone who presents themselves as an opponent to the idea of censorship could eventually see their arguments purposefully misconstrued, and ironically labelled as a purveyor of offensive misinformation.

Even Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel, the man stabbed - allegedly by a teen- during a live sermon, said he “strongly” supports the video remaining online, according to lawyers for Elon Musk’s X.

Then it was time to see how Australia reacted to the news that the right to free information was being whittled away.

Earlier this week, the ABC waded into the debate on X (formerly Twitter), coyly asking the public if a government should have the power to restrict content inside its borders even if it’s being shared across the globe.

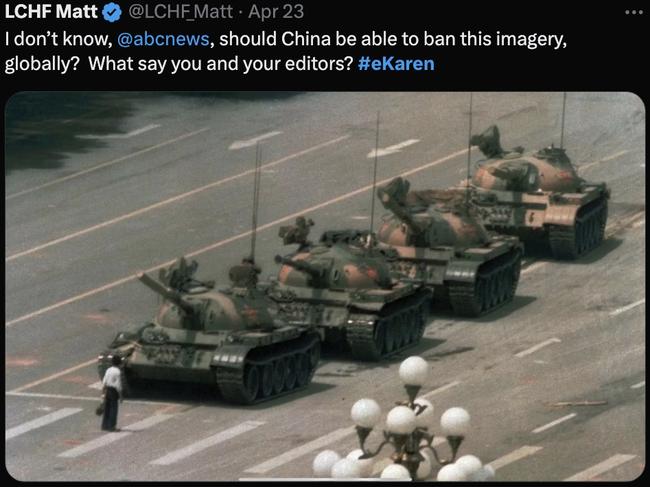

One X user’s reply perfectly summed up the sorry mess we’ve somehow found ourselves in, posting a picture of the infamous Tank Man from the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Nearly four decades on, it is still illegal in China to speak about or share images of what has become one of the more prominent examples of state censorship.

Even more chilling is the fact the identity and fate of Tank Man; a protester who famously stood in front of four tanks in the square in a now-iconic shot, is still unknown.

Some believe he was hauled away and shot on the spot. Others claim he escaped, scurrying away from the army while still carrying his shopping bags.

We may never know, such is the power of a state that has for decades pushed for complete control over information inside its borders. We were taught in school about the dangers of an all-encompassing government, pinning up foreign nations as the distant, looming bad guys.

Let’s stop taking pages out of that book.

Of course, this is an extreme example. There is no suggestion the Australian government is an oppressive beast hellbent on locking up political dissidents.

But if we aren’t careful, powers of censorship will be misused, or at least stuck in a bloated and expensive grey area.

Online censorship ain’t nothin’ new

Policing information online is nothing new. Throughout the pandemic, governments in developed nations pushed through some of the most stringent measures yet seen to clamp down on what they deemed as harmful misinformation.

The most notable examples were released in The Twitter Files in 2022, where there was plain-as-day evidence that the US government had requested its own separate portal on the platform to flag and delete content it believed to be misinformation.

Some of the “disinformation” that was deleted were claims from outlawed scientists who warned the mandated vaccines would not stop community transmission, running opposite to what was trumpeted by government health officials and presidents around the planet.

Hm.

But as the months went by, the grey areas grew. Several things about the pandemic that were initially believed to be false were flipped on their head as research naturally continued.

Journalist Matt Taibbi, who worked on a section of the bombshell document drop, said pre-Musk Twitter had begun policing speech purely to “combat the likes of spam and financial fraudsters”

“Slowly, over time, Twitter staff and executives began to find more and more uses for these tools. Outsiders began petitioning the company to manipulate speech as well: first a little, then more often, then constantly,” Taibbi wrote on X.

“Both parties had access to these tools. For instance, in 2020, requests from both the Trump White House and the Biden campaign were received and honoured.

“However: this system wasn’t balanced. It was based on contacts. Because Twitter was and is overwhelmingly staffed by people of one political orientation, there were more channels, more ways to complain, open to the left (well, Democrats) than the right.”

Double hm.

Dutton says policing the world is ‘silly’

It’s clear both the Labor and Liberal Parties have a dog in the fight.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton, while labelling the eSafety Commissioner’s war against Musk “silly”, completely missed the point when explaining his stance this week.

“We can have a say about what images are online here in our country, we can’t influence what happens elsewhere in the world. I think it’s silly to try that,” he told 2GB radio on Thursday.

“We can’t be the internet police of the world, I know the Prime Minister’s trying that at the moment.

“If we have a situation where you’ve got a cleric being stabbed, and that’s inciting violence, the law is very clear about the ability to take that down – but I don’t think the law extends to other countries, nor should it.”

Someone get Mr Dutton on the blower and get him to Google what a VPN is.

Australians who want to get around the new measures will just shell out for one and browse as if they were in the Netherlands.

Will the government eventually move to outlaw these services?

Probably.

But there really is no stopping the internet.

More Coverage

Originally published as Image of Tiananmen Square ‘Tank Man’ poignantly sums up Australia’s online censorship debate