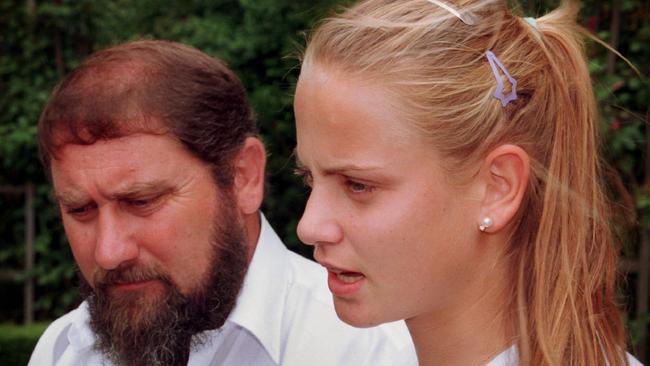

JELENA Dokic is one of the brightest tennis stars Australia has ever produced, but her fans always knew there was something dark about the relationship between Jelena and her powerful, overbearing father Damir Dokic. Now, in an upcoming autobiography written with The Sunday Telegraph’s Jessica Halloran, Jelena finally reveals the frightening truth about her childhood of fear and violence. She wants her story to be understood as a tale of survival. “My story hasn’t been a fairytale, but I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me — I am luckier than most,” she writes.

FORMER tennis champion Jelena Dokic has written an explosive new book claiming she endured a childhood of horrendous violence at the hands of her father Damir Dokic.

In her autobiography ‘Unbreakable’, released tomorrow, Dokic alleges her father whipped, beat, kicked and spat at her in a frenzy that began the day she picked up a tennis racket at age six and continued until she escaped the family home at 19.

“He beat me really badly,” Dokic told The Sunday Telegraph in a special interview that will also air on FoxSports. “It basically started day one of me playing tennis,” Dokic said. “It continued on from there. It spiralled out of control.”

Jelena Dokic’s allegations include:

—Damir Dokic beating her so badly she once lost consciousness

—Dokic repeatedly whipping her with his leather belt because of “a mediocre training session (or) a loss, a bad mood”;

—Dokic spitting in her face, pulling her hair and ears and kicking her in the shins with sharp dress shoes, leaving her bruised and bloody;

—Dokic unleashing constant vile verbal abuse including calling his teenage daughter a “slut” and a “whore”.

Damir Dokic, who now lives in Serbia, did not respond to attempts to contact him for a response yesterday.

Jelena Dokic said she contemplated suicide during her years of emotional and physical abuse, but said the emotional tirades “hurt more” than the physical attacks.

“[The beatings] happened almost on a daily basis, but I also struggled with the emotional situation,” Jelena Dokic said. “Not just the physical pain but the emotional [pain], that was the one what hurt me the most … when you are 11, 12 years old and hear all those nasty things … that was more difficult for me.”

Jelena Dokic said when she was just 17 in 2000, her father abandoned her at Wimbledon after her semi-final loss to Lindsay Davenport, leaving her at the courts and refusing to allow her to return to the hotel room she was paying for.

This was one of the hardest moments for me,” she said.

“If I had to pick one this was the one. If you are made to sleep at the courts …”

Even though she reached world No. 4 by the age of 19, she said her father was never satisfied by her achievements on the court.

Dokic’s book also details her life as a young refugee enduring extreme poverty, racism and bullying after the family’s arrival in Australia from the former Yugoslavia in 1994. She was told by an Australian player on a junior tennis tour “go back to where you came from” while an unnamed Australian coach said he would not have let Dokic “come back to Australia, let alone play for wildcards”.

She also reveals in the book the worst beating she ever received, after a first-round loss at the du Maurier Open in Canada in 2000.

“It was a really nasty memory that will stay with me forever … I ended up fainting,” she said in the interview. “He beat me really badly.”

She added: “The better I played the worse he got. Which is the one thing I couldn’t understand.”

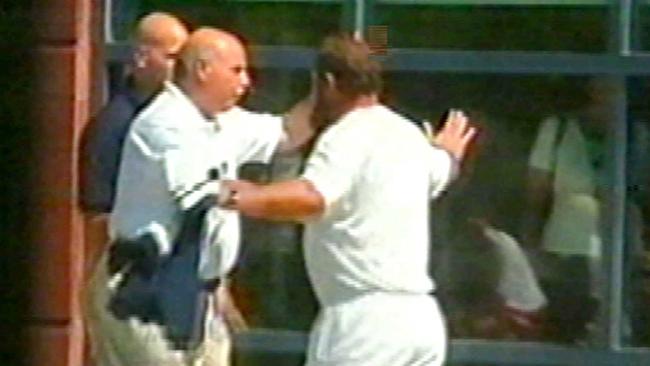

In ‘Unbreakable’ Dokic details Damir’s drunken behaviour at Wimbledon and the US Open — episodes which led to the man dubbed “tennis dad from hell” to be banned from the women’s tennis tour for six months.

She said her father’s decision in 2001 to force her to switch nationalities from Australia to Yugoslavia is her greatest regret.

“If there is one thing I could take back what he did or certain decisions, leave all the physical stuff and abuse, this was the one I regret,” Dokic said in the interview.

“If I could turn back time, I would like to take back him making me switch from playing for Australia and playing for Yugoslavia … a few years later I came back and played for Australia ... but so much damage was done.”

Dokic said she doesn’t “hate” her father after everything he subjected her to.

“I tried to make things better [between us] but it is not an easy thing to do,” she said. “I don’t think he understands the things he has done. I don’t think he has taken the responsibility ... it’s difficult to find a middle ground with him. It’s either his way or that’s it.”

In 2009 Damir Dokic — who subsequently served a year in a Serbian jail for threatening to kill the Australian ambassador — admitted striking his daughter.

“If I was ever a little bit more aggressive towards Jelena, it was for her sake,” Mr Dokic told the Serbian newspaper Vecernje Novosti.

“When I was young, I was beaten by my parents and I am now thankful to them for that, because that helped me to become the right person. Anyway, is there any parent who didn’t do that at least once or twice — of course, for the sake of their children?” he said.

Watch the full Jelena Dokic interview on Fox Sports 501, Wednesday, at 6.30pm.

‘Unbreakable’, by Jelena Dokic and Jessica Halloran will be released tomorrow by Penguin Random House, RRP $34.99

The following is an edited extract from Unbreakable by Jelena Dokic and Jessica Halloran, published by Penguin Random House Australia on 13 November 2017, RRP $34.99

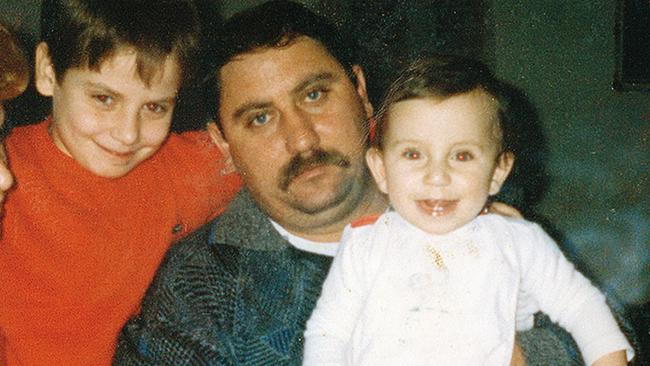

AUSTRALIA, 1994

Every morning I wake at home and worries assail my mind before I have even lifted my head off the pillow. How can I make sure he doesn’t hurt me today? How can I make sure he doesn’t explode? These days that’s hard — he’s getting more aggressive.

It feels as though ever since we walked through the doors of Sydney Airport he has been panicked, fearful and miserable. His eyes are now never soft like they sometimes were in Serbia; he is still grieving the death of his father. Nor have my parents been able to get jobs. Once more, at times our main meals are bread and margarine with salt. On the day before we are due to receive our fortnightly government benefit we are usually down to our last eight dollars, and six of those must be spent on train and bus fares for Dad and me to get to White City.

Fortunately my work is paying off. At White City, on my hectic training regimen I am improving at a rapid rate. I’ve made the kind of gains in my tennis over three months that most other children would manage in three years. It’s not normal, but it’s impossible not to improve like this when you’ve got someone like my father behind you. There is no other option but to succeed.

He tells me I must succeed as this is our only way out from this situation here in Australia. He tells me this daily — in our Fairfield apartment, on the way to training: ‘You are our way out.’

And I know that I am. Absolutely, I am our only chance of a better life in this new country.

I begin to feel that the stakes are so high for my family around my success or failure that every shot has to be perfect. Indeed, Dad tells me he wants me to be perfect on the tennis court. But even when I deliver perfection he wants more. When I reach No. 1 in the under-14s, he demands I should be No. 1 in the under-16 age group. It doesn’t take much to set him off into a rage.

For a man who rarely even sipped alcohol in Yugoslavia he is drinking hard here in Australia. My guess is that he starts to drink because of the pain he is feeling being away from his country. He drinks to cope with being an outsider. He drinks to cope with pressure. He starts downing cheap white wine mixed with soda water, a spritzer, from the early afternoon well into the night.

Things aren’t all bad for our family. There are some good times — a few hours when we have a happy family dinner with Dad cooking up an old family favourite. But it never takes long for the misery to descend again. I spend less and less time with my mum — everything is tennis-related now; it’s 24/7 — about the game and my dad making me successful.

The belt is brown, its leather thick and hard, it feels as sharp as a knife when it’s whipped against my skin.

As the months roll on it becomes more difficult to make him happy. Even if I have a good session, he picks on little things. He tears into me about some technicality of a shot, yells if my feet are not working hard enough. He verbally rips me apart if I am not intense enough. And he has become more violent.

The belt is brown, its leather thick and hard, it feels as sharp as a knife when it’s whipped against my skin. A mediocre training session, a loss, a bad mood — any of these trigger him to bring out the belt. My losing particularly sends my father into a rage. I rarely lose but when I do the consequence is brutal. The consequence now is often a belt-whipping. I can see he has decided slapping and hitting me are not enough of a punishment.

Whenever I’m losing he paces up and down beside the court. Then, if he can sense the match is over, even before ‘game, set, match’ is called he will storm off. And after I’ve shaken hands with my opponent and the umpire, packed up my racquet bag and walked off the court, I have to play an awful game of finding him.

I have to find him even though I’m scared to my bones about what he is about to do to me.

Inevitably he will be skulking where no one can see him — behind tennis clubrooms, trees, outside courts, in the car park — and he will scowl at me as I approach having finally caught a glimpse of him. If no one is looking, there will be a verbal barrage — these have got nastier — and then he’ll hit me a number of times, stinging my cheeks. He often spits in my face. He pulls my ears. But the punishment never ends at the courts. When I get home he screams that I am hopeless, a pathetic player. Over and over. He also screams at me that I am ‘stupid cow’, ‘dumb’, ‘an embarrassment’ and ‘a whore’. And there, with only Mum and Savo looking on, he is able to strike me quite hard.

My mother sometimes says in a sad, quiet voice, in a polite tone, ‘Please stop.’

He always turns to her and yells ‘Shut up and piss off’ and resumes the beating.

She remains close by, witnessing this hell unfold. Savo sometimes sees me being beaten but usually they send him away to his room to play.

After the hits, out comes the brown belt. At that point sometimes he orders my mother and little brother out of the apartment. I get to know that belt really well. He wears it all the time and when he whips it out of the belt holes, I start to shake. He orders me to be quiet and not to cry — to show no emotion. Then he tells me to take off my shirt. It hurts a lot less when you have your shirt on and that’s why he makes me take it off. I stand in my bra, my back to him, and he orders me not to move as he hits me. Often he almost slices my skin with the belt. Sometimes the pain is just too much so I run away to a corner of the living room and he chases me. He grabs me, physically turns me around so my back is to him and he can whip me again. It hurts like hell. It is hell.

He divides up his abuse of me. He will emotionally abuse me, then whip me. I steel myself through the pain. He will stop but then will verbally berate me for ages. ‘Jelena, you are hopeless’ is the message.

When it is finally all over, he never shows remorse. It’s as though he thinks hitting me is the right thing to do. Or he’ll blame me: ‘It’s your own fault, you made me do it,’ he’ll sometimes say.

Somehow I can go to school or back on court the next day and act as if it never happened. I force myself to switch off and erase the pain from my mind. I use an enormous amount of energy to push the hellish episodes of abuse out of my head.

My father makes sure I wear long-sleeved T-shirts to school and training to try to cover up the marks: those deep-blue, purple bruises on the tops of my arms, all over my back that remind me of his anger. I don’t want to see them but sometimes I dare myself to look in the mirror at what his beatings have done to me. And when I look, some- times I can barely see a centimetre of unmarked skin. Almost my entire back is taken up by blue, red, purple bruises and welts. Sometimes my back is bleeding. It hurts to touch and aches.

No one asks about the bruises. I don’t know if they see them but certainly nobody asks.

But some days I can’t hide his abuse. One day he hits me, misses the side of my head and hits my left eye. It goes black, blue and purple. I miss training for three days. I miss school. My father hides me away so no one can question what has happened.

During training sessions when I am not doing things right for him and there are people around, or I am on the court with a coach, he will call me over to the side of the court. There he will pretend he is giving me a towel and twist my hand aggressively underneath the cloak of the towel. Sometimes he grips my arms so hard underneath it and makes sure his fingernails pierce my skin. ‘You are practising like shit,’ he sneers. ‘You will see what you are getting afterwards.’

On the long runs he makes me do, after training for hours on the court — up to ten kilometres on the really bad days — I go into my own world and start talking to myself. I reassure myself I will be okay, that I can do this. That I can survive. I also talk to myself because I have reached a point where I feel like I am not talking enough. I will never reveal to anyone what happens to me because I am so afraid of my father. I will never say anything to anyone — I don’t consider telling a single soul — there would be hell to pay if even one person were to find out.

My grandmother has now arrived in Australia and lives with us; my Uncle Pavle is still in Serbia but is considering coming as well. No doubt my parents know what is going on at home with our loved ones and the war. But I have no time to take notice of anything or anyone these days except tennis.

As my star starts to rise on the junior Australian circuit, Dad’s behaviour worsens. It’s weird but the better I play, the worse he seems to get. He continues to drink at tournaments. On rare occasions when I’m runner-up, he takes my ‘losing trophy’ and smashes it.

One day I lose in the final of a tournament in White City. This is seen as a failing in my father’s eyes. He’s in a mood, he’s already hurled a truckload of verbal abuse at me on the walk to the station, and we are now standing on the platform at Edgecliff. He suddenly snatches my ‘losing’ crystal trophy out of my hand and pelts it into a nearby brick wall. The sound of glass breaking echoes around the station as it smashes, causing a bunch of commuters to turn to see what’s happened. I crouch to try to pick up the fragments on the platform. I put them in a nearby trash can while everyone is sadly watching on. I felt utterly ashamed and miserable. Bitter tears stream down my face as I picked up the shards. Sometimes he throws the balls from our bucket all over the place and I have to pick them up. I am anxious that doesn’t happen now. He’s already made me carry all our kit to the station — another one of his punishments.

He often spits in my face. He pulls my ears. But the punishment never ends at the courts.

His drunken madness bubbles to the surface again one afternoon in a round-robin event at a suburban tennis club in Sydney. After an epic match against an older girl, the minute we are out of sight of other parents and coaches he sprays me with abuse as my mother and Savo, who have also been watching the match, stand helplessly to one side. On this occasion he thinks I won — he hasn’t seen the score- board — and that I have just played terribly. He hurls a heap of verbal abuse my way.

Thank God he doesn’t know I actually lost.

The rage still comes my way as we walk as a family to the station to go home to Fairfield. He spits at me as I cower, hoping for a miracle, for the abuse to end, though I know it won’t. I am really concerned by the public humiliation as we make our way to the station. Then, for some reason completely beyond my comprehension, Mum suddenly decides to break the truth to him. ‘No, she lost,’ she says. I am horrified she has told the truth. Stunned.

He whips around, looks to see if anyone is watching, and fronts his big frame up to me. He’s towering over me and I am bracing. ‘You lost?’ he yells. Spots of spittle land on my face. He takes off a shoe and hits me over the head several times. He wears a hard-soled dress shoe. It feels like a cricket bat against my head. The pain is intense.

I am cowering now. Trying to ease the blows by going with every strike. He whacks over and over again until all his anger is spent. We then continue to the station and board the train in silence. When I get home the abuse continues; the belt comes out and the barrage of verbal insults begins again. My head is throbbing from the thumps of his shoe, my back stinging from the strikes from his belt, and my heart is broken.

*In an interview with a Serbian newspaper in 2009 Damir Dokic admitted to hitting his daughter. “If I was ever a little more aggressive towards Jelena it was for her sake,” the newspaper quoted him as saying. “When I was young, I was beaten by my parents,” Mr Dokic said, “and I am now thankful to them for that, because that helped me to become the right person. Anyway, is there any parent who didn’t do that at least once or twice — of course, for the sake of their children?”

JULY 2000

I don’t know where my dad is. I’m standing in the plush Wimbledon players’ lounge waiting, looking around for him: we’re due to go out for a nice dinner with my managers, Ivan and John. I am seventeen years old and I have just played in the semi-finals. Of Wimbledon.

Surely, you’d think, he would be okay that I got this far at the All England Club. You would think. At the end of the match, as I shook Lindsay’s hand, I looked up to the stands and saw my father bolt out of his green seat, nothing but the back of his burly frame rushing from Wimbledon’s Centre Court. Usually after my matches, he stands around somewhere near the players’ lounge and I have to find him. But today there’s neither sight nor sound of him. I called his mobile after I finished my press duties and he didn’t pick up.

This has been my greatest run ever in a grand slam and I want to know what he’ll say, and to organise how we will get to dinner with Ivan and John. So I call him again, and this time, finally, he picks up.

The dull slur in his slow, loud voice tells me he is drunk. I know this tone; it’s the tone of white wine and probably a few glasses of whisky. He is angry. Furious that I lost. His voice booms down the phone. ‘You are pathetic, you are a hopeless cow, you are not to come home.

You are an embarrassment. You can’t stay at our hotel.’

‘But, Dad …’ I say quietly, trying to plead with him.

‘You need to go and find somewhere else to sleep,’ he yells at the top of his voice. ‘Stay at Wimbledon and sleep there somewhere … Or wherever else. I don’t care.’

He hangs up.

I have just made the semi-finals of Wimbledon. But in my father’s eyes I am not good enough to come home.

Players around me are getting on with life, chatting, eating dinner, winding down with their coaches. I am alone and shattered. I have no money — well, no access to it — no credit card. It is Dad who has all that. He controls everything in my life.

Emotion starts to overwhelm me. Failure — I’m a failure. Minutes tick by, and then hours. I tuck myself away on a small couch in the corner of the players’ lounge, hoping no one notices me, and eventually the place is empty.

At around 11pm the cleaner arrives. She sees me in the corner and comes over. ‘You can’t stay here,’ she says softly.

I make the confession: ‘I have nowhere to sleep tonight.’ As I say it, the reality hits me. The tears prick in the corner of my eyes.

‘I have to let the tournament authorities know,’ she says.

Wimbledon’s referee, Alan Mills, arrives. ‘What happened?’ he asks gently.

‘I have nowhere to go,’ I say. ‘I have nowhere to sleep.’

Hot tears are running down my face, but I don’t let on that my own father has banished me: as always I must protect him. Alan, however, seems to know what’s going on. My management agency, Advantage, has rented a beautiful house in Wimbledon village; Alan calls my managers and they say they will take me in. He arranges for a tournament car to take me to the house.

I arrive sobbing and Ivan and John look concerned when they see me. They explain they’d called my dad earlier in the evening trying to locate us, and my nine-year-old brother, Savo, answered. John says he could hear my father’s voice in the background. Apparently Savo said simply, ‘My dad isn’t here.’

I am both heartbroken by my father’s rejection and embarrassed by it.

I’m shown to the spare room. At least I didn’t get a beating from him. As I wait for sleep, through the shock and hurt I start to realise that I might never make my father happy. That I might never be good enough in his eyes.

This is an edited extract from Unbreakable by Jelena Dokic and Jessica Halloran, published by Penguin Random House Australia on 13 November 2017, RRP $34.99

If you or someone you know needs help, phone LIFELINE on 13 11 14

Venus effect in full show as 45-year-old ends 16-month layoff

Venus Williams has made her return from a 16-month layoff at the DC Open, wowing a capacity crowd in the doubles ahead of her singes comeback.

‘Knee cooked’: Kyrgios blow before major return

A doubles defeat doesn’t sound much like a return of significance but for Nick Kyrgios it was a stepping stone to the US Open after another knee issue.