The untold story of the silent protest against Chinese swimmers by two of Australia’s highest profile swimmers in the 1990s

Mack Horton’s stance against Sun Yang received widespread media coverage. But there was another protest more than 25 years earlier involving two of Australia’s best swimmers at the time, which has yet to receive any exposure, until now.

Olympics

Don't miss out on the headlines from Olympics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The loudest protests always start with silent acts of courage.

Before the angry mob gets together, there’s often brave individuals selflessly putting themselves in harm’s way to sound the alarm bell.

That’s long been the reality for anyone willing to call out China’s appalling record of doping and bullying because the repercussions can be frightening.

While sporting officials the world over have joined forces to call for an independent investigation into the latest mass doping scandal in China, the original dissenters went it alone.

The first public demonstration against China’s swimmers took place well away from the spotlight, more than three decades ago, at the inaugural short-course world championships at Palma de Mallorca in 1993 and was done by Australians.

Beijing does not take criticism lightly so the actions of the brave Aussies were considered so risky at the time that team members have never spoken about it until now, with one senior team official and a number of swimmers only agreeing to reveal what actually happened to add some context to the shocking revelations this week that 23 top Chinese swimmers were secretly acquitted in the lead-up to the 2021 Tokyo Olympic despite testing positive to the banned drug trimetazidine.

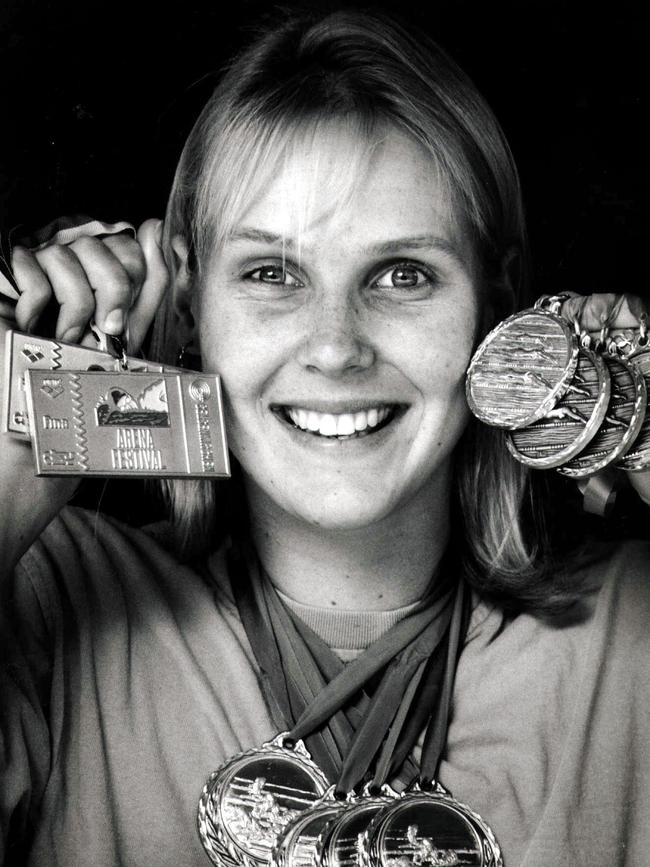

Going against their coaches’ advice, Linley Frame and Samantha Riley staged a peaceful protest at the medal ceremony for the women’s 100m breaststroke, where Frame had finished second and Riley third behind 16-year-old Dai Guohong, who broke the world record.

In a precursor to Mack Horton’s explosive objection to Sun Yang’s participation at the 2019 world titles, Frame and Riley politely stood their ground instead of stepping on the podium with the stranger collecting the winner’s medal.

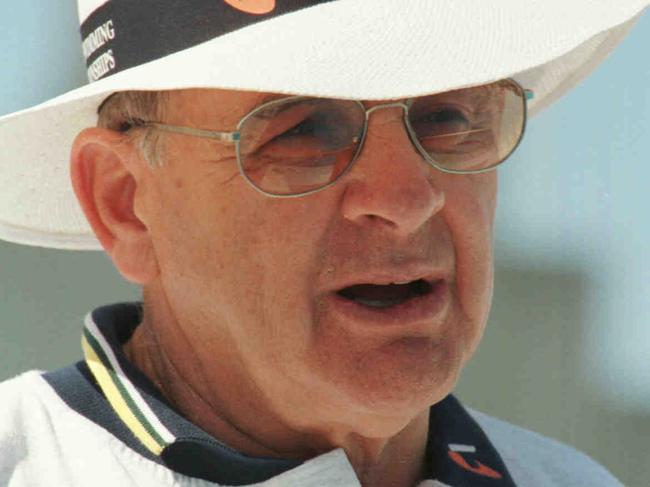

Ian Hanson, the team’s media officer at the time, said the two Dolphins had considered boycotting the ceremony altogether but were warned against it by the head coach Don Talbot, so they settled on a compromise.

“That was the way that the girls wanted to protest against what was going on so they just stood on the ground,” Hanson said.

“Similar to Mack, but without the attention because it was the first ever (short-course world championships) and no broadcast.

“When he (Talbot) was in charge, he wanted to take the brunt of any media on that. He just wanted the athletes to concentrate on what they were doing. He was very savvy. He had the smarts, but privately he was seething like everybody else.”

Because the internet had still not been commercialised and there were no live blogs or tweets in the early 1990s, the defiance of the Australians never got out but the spark that triggered their objection became known to everyone at the long-course world championships in Rome the following year.

Tall, packed with muscles, and with unusually deep voices, the Chinese women had already aroused suspicions after winning gold in 12 of the 16 events in the Italian capital.

Their domination was eerily reminiscent of East Germany’s monopoly on women’s swimming in the 1970s and 1980s, which was later shown to be assisted by anabolic steroids.

The proof of GDR’s state-sponsored doping regime was revealed after the fall of the Berlin Wall, leaving a number of coaches out of work. Several, including Klaus Rudolf, simply packed up and moved to China.

Convinced something fishy was going on, Talbot noticed that the Chinese women collecting the medals at the ceremonies – and thus being taken away and tested for drugs – were not the same swimmers who had just won the races.

Watching intently, he observed them being switched in the warm-down pools after each final they won, baffling the drug testers from remembering who’s who by all diving underwater together.

Talbot lodged an official complaint with FINA, swimming’s world governing body as it was known at the time, but his gripe fell on deaf ears, with no action taken, even though delegates from other countries spotted the deception and also reported it.

“There was no greater anti-doping campaigner than Don Talbot because he stood up for the team and he stood up for his athletes. He knew how much they trained and what they deserved and he knew they didn’t deserve to be beaten by drug cheats,” Hanson said.

“Don really went to town but as far as the athletes were concerned, he didn’t want them to lose sight of what they were there for.

“He didn’t want them to be distracted. He just wanted them to roll their sleeves up and race harder and prove that they could beat them.

“Don told them to take it out in the water, ‘When you race, you have to show them that you don’t need drugs to win these races.”

To this day, the Australian swimmers have maintained a code of silence around what happened in Mallorca and Rome.

But one member of the team, speaking on condition of anonymity, said everyone knew something was seriously amiss with the Chinese.

“There was nothing any of us could do but our best. No one was catching them. They were ahead of the game,” the swimmer said.

Another team member, who also asked not to be identified, said no-one ever blamed the individual Chinese swimmers because they were pawns in something out of their control.

“I watched the excitement on the faces of the Chinese girls on the podium and I really believed they probably didn’t know they were cheating,” the swimmer said.

“I don’t think they knew. I don’t see how you could be that excited and proud of yourself if you knew. I think it was systemic and the athletes aren’t to blame.”

Only three women managed to beat the Chinese for gold in Rome: American Janet Evans, Germany’s Franziska van Almsick and Riley, who won the 100m and 200m breaststroke titles.

Australia’s ‘Madame Butterfly’ Susie O’Neill won bronze medals in both of her races and did agree to speak on the record, though she said she was still uneasy discussing the tumultuous run ins with the Chinese

“Even now I feel funny saying anything about China, because it just got drummed into me so much not to talk about it,” she said.

“It’s weird now when I see athletes speaking up, I think it’s great but it’s just something that doesn’t come natural to me.

“I kind of just shut it all out and it’s only just when I read it just recently in the paper that I remembered what happened.

“But I’ve been reflecting on it a bit lately, before this all came out.

“That actually changed the whole trajectory of my swimming career, maybe for the better. I left my coach after that because I got third behind two Chinese in the 100m and 200m.”

O’Neill went on and won gold medals at the next two Olympics.

Just like the most recent scandal, the Chinese responded angrily to any suggestions they were doing anything untoward, but it wasn’t long until they were caught red handed.

A month later, at the Asian Games in Hiroshima, seven Chinese swimmers, including two recently crowned world champions, were busted for the banned drug dihydrotestosterone, setting in motion a 30-year cycle of distrust that continues today.

Despite insisting they have cleaned their act up, Chinese swimming has continued to be plagued by sporadic cases in the years since.

In 1998, Yuan Yuan and her coach were caught at Sydney airport smuggling 13 vials of muscle-building human growth hormone into Australia ahead of the world championships taking place in Perth.

More than 40 Chinese swimmers – more than triple the total from any other country – tested positive to performance-enhancing drugs in the 1990s alone.

The figures have decreased but there are serious concerns about the accuracy of the reduced numbers because of the unreported cases in China that only get leaked by the media.

There are also worrying questions about China’s cosy relationship with FINA, WADA and the International Olympic Committee.

Under siege from the media after Yuan got nabbed carrying enough HgH to fuel the entire Chinese team, FINA threw a lavish last-minute party for the press, with the best barbecued seafood and prime steaks and bottles of Australian wines.

Not exactly known for their discipline, the fourth state took full advantage of the unexpected offering, with many arriving at the pool the next day nursing hangovers.

It was only then that FINA dropped the bombshell news that four more Chinese had been caught.

FINA’s relationship with Sun, China’s most successful and controversial swimmer, has also been heavily scrutinised.

A triple Olympic champion with a perfect technique that makes swimming look effortless, Sun also tested positive for trimetazidine in 2014 but got off light, apparently serving a three-month suspension.

But there remains real doubts about whether Sun actually did spend any time out of the water following reports it was concocted by Cornel Marculescu, the former Romanian secret police agent who was employed as FINA’s executive director for decades.

Marculescu is best known in Australia for publicly embracing Sun on the pool deck at the 2016 Rio Olympics after his spat with Horton, then dismissing Sun’s first doping charge as “minor.”

“You cannot condemn the stars just because they had a minor incident with doping,” he once said.

But British investigative journalist Craig Lord once emailed Marculescu to address whispers that the Chinese had tried to let Sun off the hook.

“Please be sure that there are no secrets whatsoever related with Sun Yang’s adverse analytical finding (AAF),” Marculescu wrote back. “We had to tell China they must have a penalty to be inside the WADA rules and they had no choice.”

Sun’s special relationship with FINA came under further examination in 2019 when it was revealed the Chinese authorities had again absolved him of an anti-doping violation, this time for smashing his samples before they could be tested.

FINA supported the decision, which again only came to light through the media, with Lord breaking the story in The Times.

The outrage was instant and led to separate protests by Horton and Britain’s Duncan Scott at the 2019 world championship, which did not go unnoticed.

Horton and Swimming Australia both received official warnings from FINA.

Less than a week later, media were tipped off that Australia’s Shayna Jack had tested positive for ligandrol, even though her results were meant to be confidential.

Marculescu has always denied FINA was the source.

Meanwhile, Horton and his family endured years of abuse from Sun’s fanatical supporters.

Horton received so many death threats that he lost count of them.

His parents home in Melbourne was broken into while gangs would sometimes assemble outside the home in the middle of the night banging pots and pans ang throwing faeces and broken glass into their hard. The education technology business that Horton’s father ran was targeted for cyber attacks.

Sun was given an eight-year ban, which was later halved on appeal, even though the judges’ final report was damning, with Sun’s entourage warned on five separate occasions for intimidating witnesses and the female doping officer who conducted the tests asking never to be publicly identified.

The timing was uncanny.

Sun’s appeal was taking place in the middle of the Covid pandemic, right at the same time China was preparing its team for the Tokyo Olympics.

The selected squad included eight swimmers who had just tested positive but were allowed to compete after it was determined they had all been accidentally contaminated.

FINA was also undergoing a major change of leadership, naming China’s Zhou Jihong as the first female vice-president of the rebranded World Aquatics.

A former gold medal-winning diver, she soon found herself in hot water at Tokyo after she verbally abused a New Zealand judge for not awarding higher marks to the Chinese competitors.

The incident only came to light through a whistleblower who was a member of the official Diving Technical committee but reminded why speaking up against China sometimes comes at a price.

Zhou received a warning while the informant later lost his spot on the committee.

More Coverage

Originally published as The untold story of the silent protest against Chinese swimmers by two of Australia’s highest profile swimmers in the 1990s