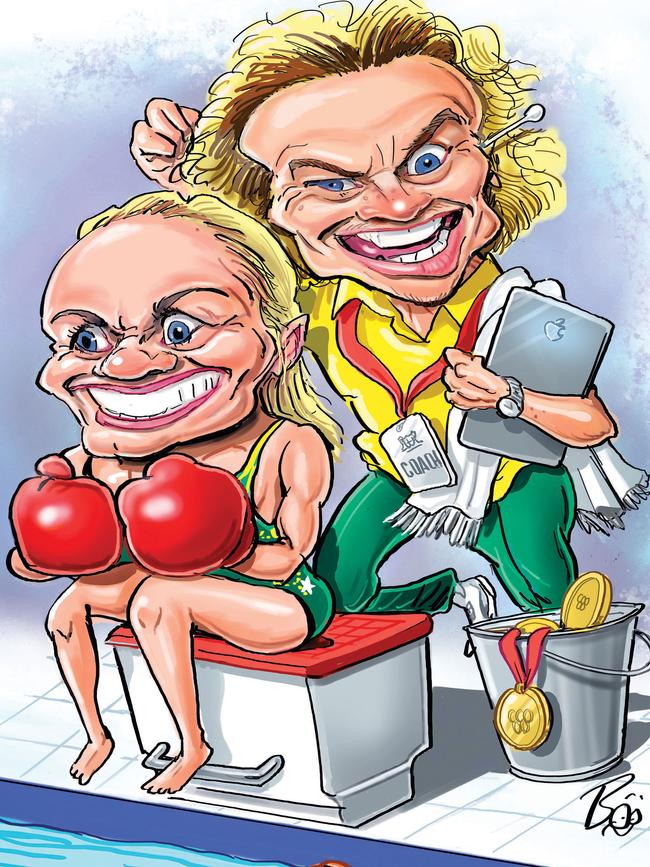

Paul Kent: Dean Boxall hits right note with his Olympic celebration, Ariarne Titmus gold medal

The emotions that pour from Australian swimming coach Dean Boxall are half a put-on, but there is a method to his madness — and it works, writes PAUL KENT.

Olympics

Don't miss out on the headlines from Olympics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

So many got it wrong when it came to the grandstand performance of Dean Boxall, the Australian swim coach who came off the top rope when Ariarne Titmus won gold.

For many Boxall was regarded as a comical figure, taking the short trip to lunacy as Titmus defeated arguably the greatest female swimmer, Katie Ledecky, to claim gold in the 400m freestyle before, he then claimed, channelling his favourite wrestler growing up, The Ultimate Warrior.

He tore off his face mask and grabbed the grandstand railing, shaking it like The Ultimate Warrior would do before grabbing his opponent and delivering the gorilla press drop. It was harmless enough.

Watch The 2021 NRL Telstra Premiership Live & On-Demand on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >

Quickly, though, the woke left rose from their coma and spat their venom at Boxall, which had the usual ingredients: spite and ignorance.

Some accused Boxall of taking attention away from Titmus to centre it on him, as if he knew cameras were trained on him at the back of the grandstand. Others, to underline their stupidity, somehow took an emotional response to a career dream being fulfilled and turned it into accusations of toxic masculinity, and then somehow tried to make it work.

Never mind that Titmus said Boxall “means everything to me” or that her father Steve described their relationship as “great”.

“That is what emotion is all about,” he said.

Worst of all, absolutely no consideration was given to the fact Boxall’s theatrics might have been all about the art of coaching, at which he is proving considerably good at.

The emotions that pour from Boxall are half a put-on. They are not entirely a man who has lost control of his emotions but, cleverly down inside, he lets loose a droplet of theatrics to elicit an emotional reaction from his athletes.

Elite performance is not all about training blocks and negative splits.

“The Americans might not like it, I don’t know,” Boxall said after he was made aware of the criticism. “But I bleed with my athletes.”

You could almost take that to mean literally.

In 2014, Boxall coached Australia at the Youth Olympics in China. He was young and already unconventional but he knew what he was doing.

Before the team left for Nanjing, Laurie Lawrence delivered the farewell pump-up speech to the Australian team. Few motivational speakers are as good as Lawrence, who makes everybody walk a little taller.

Boxall shared his accommodation with the Australian boxing coach Joel Keegan and, sitting in their room one night, Keegan remarked how good Lawrence’s speech was.

Boxall already had a slight crush on Lawrence, so needed no more urging.

He sat back and told a story about Lawrence training his swimmers one morning when they mustered the courage to complain to him about his tough training regime.

It was too hard, they complained, saying he put them through too much pain.

This offended Lawrence greatly, who was in the business of sending athletes to the Olympics to win gold medals, not merely to take part.

He knew the difference between gold and silver and simply being called a finalist was pushing through the pain barrier, which was only ever a mental barrier.

So Lawrence listened to their moans and, triggered by the word ‘pain’, walked to a nearby brick wall and dragged his knuckles down the wall, shredding the skin until blood ran over the back of his hands and down his arms.

“Don’t tell me about pain,” he said walking back to his swimmers, holding his bloodied knuckles in the breeze.

Pain was a mental state. And he was in the business of defeating pain, because that is what it took to win.

That story resonated with Boxall, whose tough training methods resulted in Titmus being the celebrated swimmer of these Olympics.

To suggest his emotional response to her gold medal swim was toxic masculinity was embarrassing and an insult to Titmus, as if by being a woman she is somehow less capable of handling Boxall’s quirks than Duncan Armstrong might have been handling Lawrence, which was celebrated.

They defeat their own argument with their stupidity, these people.

What Boxall knows and Titmus appreciates is that when athletes go to the starting line of an Olympic final, they are often so evenly prepared that the difference in performance can be their mental attitude.

Boxall has found a way to get a final emotional rise from Titmus before she races, something Titmus understands intrinsically.

There seems to be a great knock on emotional coaching nowadays, as if, by being emotional, you don’t know your stuff.

Good coaches know the mental shift immediately before an event can often be the difference, the final one per cent necessary to get the result.

Every year Queensland and NSW go into camp to prepare for Origin and every year Queensland leap upon some perceived insult from NSW as motivation.

I asked Mal Meninga about it one day, wondering why players about to play an Origin game needed some artificial motivation to get up for it.

Meninga called them “triggers”. It wasn’t so much the insult that mattered but that the Maroons had something to call on when that moment came and their lungs were burning so badly they could taste blood and they needed something extra for that one final effort.

Suddenly it made sense.

Australia could have done with some emotional coaching in the boxing ring, for instance, at these Games.

Boxing coach Kevin Smith would put a glass eye to sleep in the Australians’ corner in Tokyo.

Smith, from England, couldn’t drag an emotional response from Australia’s boxers Skye Nicolson and Paulo Aukosa and both went down narrowly, 3-2, to be eliminated from the Games.

Jeff Fenech watched on and, appropriately disgusted, but altogether too kind, called Australia’s amateur boxing bureaucracy “wankers”.

Smith rejected Fenech’s criticism, showing he still didn’t get it, saying: “It is necessary to know an athlete’s strengths and weaknesses when considering what advice to give them between rounds in a contest.”

Everything Smith told them could have been said a week earlier. It could have been mailed in, for all the good it did. They needed a trainer to, come the third round, make them rise.

Fenech knows, because nobody ever responded to a trainer’s instructions from the corner better than Fenech.

He had a trainer like Johnny Lewis in his corner who could read tempo and body language better than them all, and who knew when to tell Fenech to hit the go button and how much he had to give.

The Aussie boxers needed a trainer to make them rise, someone even like Boxall.

SHORT SHOT

The intelligent move would be to abandon the Rugby League World Cup, which is already struggling to make a quid now the Kangaroos and Kiwis have withdrawn.

Attempts to lure players for the tier-two nations or even an Indigenous version of Australia are damaging and would require just one rogue element – and rugby league has a few, as already proven – to bring it all undone.

The show of solidarity from the 16 NRL clubs on Friday, to support the Australian and New Zealand Rugby League’s decisions to withdraw from the World Cup, was the latest good decision to be made in the interest of the game.

Now it is up to the players, who should join the push to delay the World Cup until next year.

It is the best solution.

The ARL Commission is trying to do the most possible to protect next year’s NRL competition and protect the broadcast deal that delivers the game hundreds of millions of dollars.

To put this at risk while Covid numbers are still out of control in England is absurd.

In the United States, the NFL has shown how serious it is about protecting its broadcast deal by making players wear trackers and fining them for failing to follow proper Covid protocols.

The name of the game here is money.