Paralympian and former soldier Curtis McGrath in fight to justify his sacrifice after Taliban takeover

EXCLUSIVE BOOK EXTRACTS: Curtis McGrath has been forced to relive the horror of losing both legs in Afghanistan after the Taliban invaded Kabul.

Paralympics

Don't miss out on the headlines from Paralympics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Curtis McGrath should be fully focused on his mission to win Paralympic gold — not tossing and turning at night trying to justify his Afghan sacrifice.

Set to fly to Japan this week to defend his Paralympic crown, the record-breaking kayaker has revealed that he has struggled to sleep since the country he lost his legs to defend was reclaimed by the Taliban.

“Was losing my legs worth it?” McGrath said.

“Before last week I would have had no problem saying yes.”

Kayo is your ticket to the best local and international sport streaming Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Try 14-days free now >

McGrath has been forced to relive the horror of losing both his legs in an IED blast while serving as an Australian soldier in Afghanistan after the Taliban invaded Kabul.

Revealing his fears for the mental wellbeing of the 26,000 Australians who served in Operation Slipper, McGrath has also had to struggle with the question of his own sacrifice.

“I was annoyed at first,” McGrath said.

BELOW: Read an exclusive extract from Curtis McGrath’s book Blood, Sweat and Steel

“And angry. We trained and equipped 300,000 Afghans and it sounds like they just rolled over and handed their weapons to the Taliban. So yes, at first, I wondered whether it was all worth it after the price we paid in money, lives and limbs.”

A 10-time world champion, a Paralympic gold medallist, and Invictus Games ambassador who befriended Prince Harry, McGrath considers delivering the national Anzac Day address on the steps of the war memorial as his greatest achievement.

McGrath has a deep empathy for those that served in what is now being described as a wasted war.

“I have been trying to gauge the thoughts of my fellow veterans and it is a mixed bag,” McGrath said.

“Some are a little ashamed and angry at the situation. And they have every right to feel like that.”

The favourite to win gold in both the K1 (kayak) and the V1 (canoe), McGrath’s Paralympic preparation has been interrupted by the question of his sacrifice.

The 33-year-old has been devouring news stories and scouring forums. Has also been struggling to sleep.

But ultimately it was not on a website that he found his justification. It was an image of an old man from his time in Afghanistan that will forever be etched into his mind.

“I thought of the man that exposed himself to the Taliban to tell us where the insurgents had buried IEDs,” McGrath said.

“With insurgents watching on, he walked from his village and to our checkpoint to help us. It was his courage that allowed us to remove a series of IEDs. And I am sure by doing that we saved lives.

“So I am not ashamed. I know what we achieved personally. I saw the terrors of insurgency on the ground. Witnessed first-hand the cruelty of the Taliban. We went there and tried to make it a better place. We had to.”

As for the IED that took his legs. The metal laden bomb that forced him to have nine surgeries in three different countries.

“I could have been a school bus that drove over it if I hadn’t stepped on it,” McGrath said.

“So I wouldn‘t change a thing. And that is why I can justify my sacrifice. Regardless of what happens now, I know I made a difference. Still my thoughts are with both the people of Afghanistan and the veterans who may be struggling to deal with what has happened.”

Read the extract from Blood, Sweat and Steal

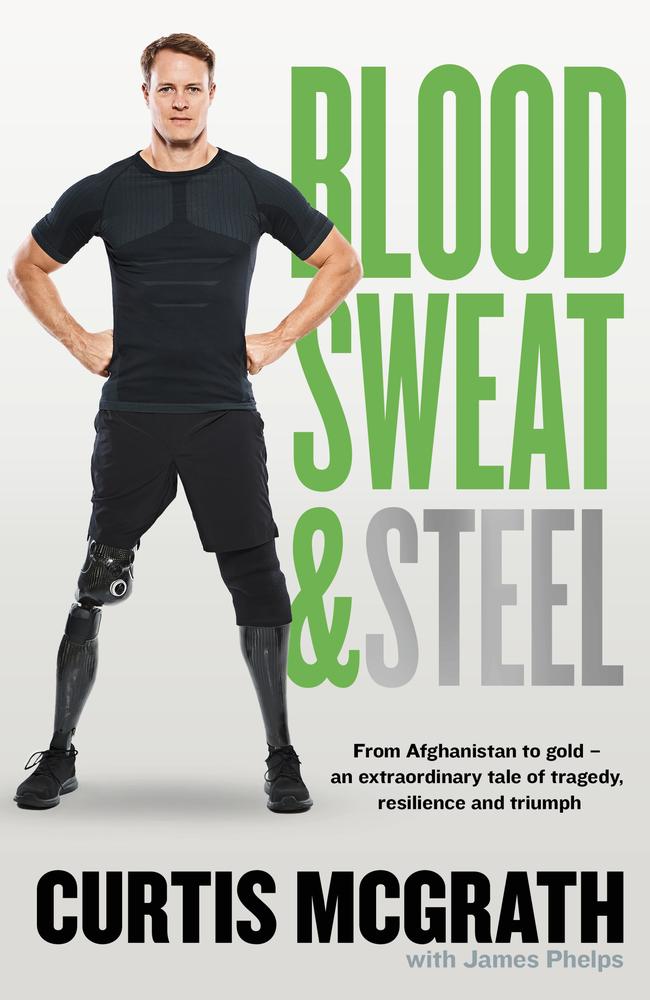

In his soon to be released book co-written by Sunday Telegraph journalist JAMES PHELPS, Australian Paralympic star CURTIS McGRATH relives the horror of losing his legs in an Improvised Explosive Device blast while serving as an Australian Army combat engineer in Afghanistan. News Corp Australia has obtained exclusive extracts from Blood, Sweat and Steel, an autobiography that tells the remarkable story of how McGrath found the courage to put the horrors of war behind him and become one of Australia’s most inspirational athletes. McGrath was just 24 and was three months into his tour Afghanistan when he was sent out to clear IEDs in Taliban stronghold near Khaz Uruzghan.

Below is an edited extract from Blood Sweat and Steel by Curtis McGrath with James Phelps to be published by ABC Books on 10 November 2021, RRP $39.99.

I WASN’T searching for landmines as I walked. The trail had already been cleared and there were fresh footprints everywhere, suggesting it was heavily used.

Suddenly I was on the ground.

How?

I had no idea why. I didn’t hear a bang. I didn’t see a flash. But here I was on the flat of my back, looking into a shitstorm.

Everything was dark, stirred-up sand blocking the sun. I looked around. Tried to find a hint. A clue. But I could only see dust and dirt.

‘Kiwi,’ someone screamed. ‘Where are you. Are you all right?’

I couldn’t see him. Shit. My ears were ringing so bad that I could barely hear him. I dug my elbows in the dirt and raised my torso to get a better view. And then I saw my legs. Or what was left of them…

And then the pain hit me.

I screamed.

Some people say that they can’t feel any pain after major trauma but I was in absolute agony. I was in every kind of pain. It shot and it crept. It was sharp and it was dull. It ached and it burnt.

‘Arrghhh!’

My eyelids, my earlobes, my tongue — I was riddled with pain, like I’d been cut by a thousand razors from head to toe, hit by a truck and set on fire.

The blood. Too much blood.

It was then I realised how bad it was. That blood was pouring from my wounds. From where my knees used to be.

Phweeeert! Phweeeert!

Geysers gushing, each beat of my heart sending two streams of blood onto the sand.

Stop it. Stop the flow.

But how? I had two spurting wounds and only one pair of hands. It looked as though I was losing more blood from the left.

Or you will die …

Running out of time, and without a better option, I reached down and put my hands around what I thought was the worst wound. Around the shredded muscle and exposed bone.

And then I squeezed.

‘Argggggh!’

Agony.

The pressure, as much as I could muster, stemmed a little of the flow in the left leg. The right continued the same.

Phwert! Phweeeert!

I shook my head.

Too much blood.

I’d be dead in a minute. I had to stop the blood.

Tick. Tock.

I let go of my leg and went for a tourniquet: it was my only chance. I reefed the seat belt like strap — that’s designed to cut off circulation — from the front of my body armour. All I had to do was put the loop over my leg — or what was left of it — and pull it tight. I’d then turn a heavy duty plastic lever to make it as mechanically tight as possible. Then I could move on to the next leg, another tourniquet waiting in a pouch on my arm.

With the lifesaving device in my hand, waiting to be looped, tightened and turned, I reach forward and went for my leg.

What?

My back thudded into the dirt. Lifting my torso by placing my elbows into the ground, I leant forward again.

‘F---!’

Without my legs, an anchor for the weight of my torso, I could not lean down far enough to reach my wounds. I could not hold myself up long enough to lean over. I was fucked.

Dead.

‘Help,’ I screamed.

‘Kiwi!’ came the reply. ‘I’m here.’

A saviour.

‘Pitch,’ I screamed. ‘Quick. Get my tourniquets on. PITCH! Get my f------ tourniquets on. I’m f---ed.’

He was at my side a moment later. ‘I got ya, mate,’ he said. ‘You’ll be sweet.’ He grabbed the tourniquet that was in my hand. The one that I couldn’t get on.

‘Watch my nuts,’ I screamed. ‘Make sure you don’t get my nuts.’ Yep. With all this going on I was thinking about my testicles. I might have lost my legs but I was going to make sure I kept my balls. I think Pitch might have even laughed.

‘Sweet, mate,’ he said. ‘I won’t get ya nuts.’ He looped the tourniquet over my thigh and ripped it tight.

‘Arggggh! F---!’ Don’t let anyone ever tell you that tightening a tourniquet doesn’t hurt. It was excruciating. I looked down at the leg that was screaming with hurt.

I howled again as Pitch pulled the plastic lever and tightened it beyond what he could do with his pulling power alone.

I took a deep breath. I looked down at my leg.

Stopped. No blood.

Well at least from that leg.

‘Get another tourniquet.’

Pitch ripped a tourniquet from the pouch on his chest.

‘Argh! F---!’

I closed my eyes and swallowed the pain. But it didn’t work. The pain stayed. I was about to scream again when I opened my eyes. The soldiers stopped my screams. I saw them come around the bend: Wertsy, Livo, and Merts. The cavalry was coming. I pushed myself up onto my elbows and watched them charge across the sand. They came fast. I could soon see their faces, all white, shocked and filled with fear.

‘I’m sweet,’ I said when they got close enough. ‘I’ll be fine.’

They were all looking at me thinking, No, he’s f---ed! So, I gave them a fake assurance. For a moment I was more worried about them. And then I started going into shock.

My breathing had become speedy and shallow. Too quick. I knew I was going into shock but I didn’t know how to stop it. I figured a distraction might work, so I took charge.

‘You need to get the IV kit out,’ I said. ‘You need to prime the line and make sure there’s no air in it.’

One of my rescuers went to pull the cord on the front of my vest that releases the body armour. He needed to get my gear off to check my torso for wounds.

‘It’s stuck,’ he said after giving it a reef.

‘Let me do it,’ I said, angrily grabbing the cord. I heaved the cord and released the armour. In this motion I punched Wertsy right in the chest.

‘Sorry,’ I said as he fell on his arse.

I turned my attention back to the IV. ‘Find a vein,’ I said. ‘Strap it and …’

I stopped midsentence as the first aid kit exploded. The soldier attempting to open medical kit ripped it and the contents went everywhere. He fumbled and searched for the IV.

Another soldier arrived. He was Lance Corporal Court, or ‘Courty’. A senior soldier and an experience first aider. A life saver, in fact.

‘I’ll do that,’ Courty said, grabbing the IV. ‘Move out of the way.’

‘What do we do now?’ Livo asked Courty.

I interrupted. ‘Some morphine would be good, eh?’ I suggested.

‘How do we do that?’ Livo asked.

Shit! I was the only combat first aider in my squad.

‘Snap the vial,’ I said. ‘Grab a drawing needle and draw exactly 2.5 milligrams. Now change the needle to a sharp giving needle.’

‘Where do you want it?’ Livo asked.

‘I don’t care,’ I replied. ‘Just f. king stab me.’

So, he did, although I don’t know where. I waited for the relief.

There was none.

Courty was still attempting to insert the IV. Another two soldiers were working on my legs. I pushed myself onto my elbows to see what they were doing.

‘Make sure they’re tight,’ I said after seeing they were applying bandages over what was left of my legs.

‘Sit back,’ Courty said. ‘Relax’.

I slumped back into the sand. And that’s when it hit me. This wasn’t good. I wasn’t good. This was bad.

I started to sob. Not because I thought I was going to die, but because I knew I was going to live.

I’ve lost my f------ legs!

I knew I’d never be able to live a normal life again. I knew I was fucked. That my life was over. Then I thought of Rachel. She’s going to kill me, I thought. I’m going to have to cancel Bali. She’s going to be filthy.

I have no idea why I thought that, but that’s what was going through my mind while I was bleeding out on the ground. Yep. I thought of how my girlfriend would react to a cancelled holiday. Go figure.

‘What’s your pain scale out of ten?’ Courty asked.

‘A thousand,’ I said. ‘It’s a f------ thousand.’

I was jabbed again.

Ahhhh. Finally.

The next shot of morphine worked. He dosed me up good. Real good. The pain slowly subsided; from a thousand to ten and then finally to four. To tolerable. Everything started to blur. A sweet fuzz.

I was two metres away from the extraction point when someone asked me how I was doing.

‘It’ll be all good boys, I’ll just get to the Paralympics, but it won’t be in the Green and Gold, I’ll be in the Black and White.’ They responded with a laugh and ‘I suppose you can walk to the chopper then?’

Fast forward three years and McGrath’s dream of becoming a Paralympian is set to become a reality. Having undergone nine surgeries in three different countries, rebuilt his body and learned to walk on metal legs, McGrath has just defied all the odds to become a world champion canoeist. McGrath is counting down the days to his first Paralympic qualification race when he answers a late night call from his coach.

‘THIS can’t be good,’ I said as I answered my phone. It was my coach, Andrea, and I was expecting her to cancel our session scheduled for 5.30am the following day.

‘It’s not. I’ve got some bad news.’ she said. ‘Something I want to tell you before you find out some other way …’ It sounded serious. ‘The International Paralympic Committee has just removed the V1 canoe from the Paralympic Games.’

‘Bullshit,’ I interrupted. ‘No way. You’re kidding me, right?’

‘No. Afraid not. I just got a call. It’s official. The V1 is being replaced by the kayak.’

I was in disbelief. The Paralympics were just eighteen months away.

I went to training the next day and took my canoe as if I hadn’t been told that I’d just wasted over a year of my life. And I was fine until I began paddling in, session over, only reality ahead.

‘What’s the point?’ I muttered under my breath as I dragged the canoe onto the beach.

I was suddenly furious. I kicked the canoe with my metal leg. Raging, I lifted my paddle into the air as I thought about all the training, all the time, all the resources that had been wasted preparing me for something that no longer existed. I was about to bring the paddle down, wanted to smash my boat to bits. I’m not sure how I stopped myself, but I did. With gritted teeth, I washed down my boat and packed it away. I then jumped in my car and drove home, no goodbyes or see you laters. I stewed as I drove.

The year had started on such a high. It was 2015. The year I’d qualify for the Paralympics. I’d upped my training, lost weight and increased my strength. Now competent in my craft, the basics down, I was going to finetune and work on all the extra things that would help me go faster. I’d been in for a good year. I’d already competed in Sydney and was looking ahead to the world championship, this year in Milan.

And then came that call. That decision. Everything had been for nothing.

Not long after I arrived home, Andrea called again. ‘You want to come back for a 10am session in the kayak,’ she asked? ‘We might as well get stuck straight in.’

I decided it was something I needed to do. My anger wasn’t going to get me to the Paralympics. I thought about what I had to do as I drove back. With the nationals just three weeks away, I had to become not only proficient in a kayak but also fast. In order to qualify for the world championships, I’d have to set an international standard time. I’d essentially miss an entire season if I failed to set that time. And while I’d still have an opportunity to qualify for the Paralympics the following year, I knew the next three weeks were make or break.

I hesitantly put the kayak into the water.

I fell into the water after only a few strokes. Splash. I went under and, at least for a moment, I didn’t want to come back up. I was utterly embarrassed. Here I was, a world champion, and I could not even stay in my boat. It was completely deflating. I thought I was past this, training wheels long ago thrown in the bin. I took a gulp of air when I surfaced. My shame turned to anger.

I grabbed the boat and began swimming back to shore. Dragged it as I stroked, determined as I’d ever been. I wanted to get to the Paralympics and this was the only way. I figured I’d conquered the V1 and I could conquer this.

I repeated the process for an hour. I’d paddle out toward the middle, fall out, swim back, and then do it all again. Paddle, sink, swim. A race kayak is not a boat you can roll over and get back into. They fill with water, so you need to drag them back to shore and empty them first. I was doing more swimming than paddling.

I couldn’t believe how difficult this boat was to balance. The V1 has an outrigger, which is a float connected to the left side of the boat. The float helps keep the boat stable, making it almost impossible to flip. The kayak — narrow, long and without a float — is harder to keep upright than tip. Anyway, I had two options; to either keep on going or quit. And I’m not the quitting type.

Thoroughly exhausted, but determined as I was deterred, I decided to go to the gym. Hard work was the only thing that would get me to where I needed to be. My phone rang when I got home. Andrea. Again.

‘Want to do another session this afternoon,’ she asked.

‘Yep.’ I went back for another hour of paddle, sink and swim.

I did three sessions the following day. Paddle, sink, swim. But I was getting a little further each time I emptied the water from the boat and went back out. Soon fifty metres became sixty metres. Then sixty metres became seventy metres. After a week, three sessions a day, I got to a point where I was actually able to keep the craft stable enough to join the rest of the squad. While far from fast, I could join the back of the group and paddle behind them.

The three weeks leading up to the nationals were exhausting, both mentally and physically. I ended up having to swim about one kilometre each session to get myself back to shore. But I got better and better and was encouraged after we did a trial race. Turns out I was only one second away from the time I needed to set.

I was as nervous as I’d ever been before a race when I arrived in Sydney for the nationals. I didn’t know what to expect. Getting close to the international time had given me a little confidence, but even making the time didn’t mean I’d qualify for the world championships. Not if I didn’t also win.

And I managed to do what I thought would prove impossible. I’d not only learned a new sport in three weeks but made the Australian team. I’d kept my Paralympic dream alive.