Swimming’s toxic culture and brutal coaching left Darian Quadrio broken. Her mental health was obliterated and she was suicidal. She bravely shared her story of suffering and survival with Jess Halloran in a bid to help and save others. WARNING: Confronting content.

Darian Quadrio wondered “what if” as the Olympic trials played out this week.

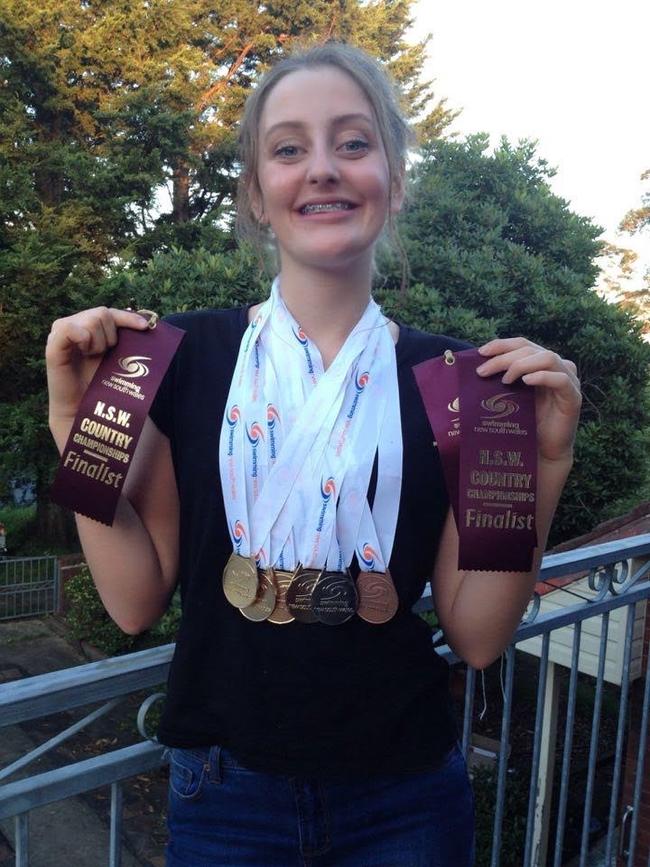

Darian was once a promising young swimmer. She broke state records and the senior coaches knew she was quite something, so much so she was included on Swimming Australia’s Talent Identification squad at the Australian Institute of Sport.

She was a potential future Olympian with Paris 2024 in her sights. At 16 she swam fast enough to qualify for the Commonwealth Youth Games team (in the Bahamas in 2017) and was publicly dubbed a “swim superstar in the making”.

But swimming’s toxic environment, a series of brutal coaching episodes, would leave her body broken, her mental health obliterated and suicidal. At her lowest ebb in early 2018 she told her mother Carrol she was going to throw herself “in front of a train”.

Darian says the sport’s “win at all costs” environment destroyed her self-belief, so at 16 when she started to battle a rare chronic illness which affected her eating (rumination syndrome) she struggled to fight it.

The disorder caused her to vomit up to 30 times a day.

On her darkest day in October 2018 the 175cm tall athlete weighed just 39 kilograms, her BMI was an alarming 13. Her friends thought she might die and Quadrio nearly did.

“Everyone was worried her heart would give out,” said her mother Carrol. “Her heartbeat was 34 beats a minute”.

Her inability to swallow, relentless vomiting, lead to her being intermittently tube-fed for two years. She was wheelchair bound due to muscle wastage. She was housebound from the age of 18 to 20. Two weeks before her 19th birthday she had a hip operation from the overtraining. Her right shoulder was so crippled she could barely open the door and today she still struggles with the pain.

“I am telling my story today not to be pitied, but to raise awareness that something needs to change in this culture,” Quadrio said.

“Young athletes’ wellbeing needs protecting. I wanted to perfect every aspect of my swimming and this was used against me. Coaches need to listen and pay attention; flogging children in the pool when they need to stop is not OK.”

“I never thought it would happen to me. I always was like; ‘I‘m going to be the one that doesn’t quit. I’m going to be the one that’s there till the end. I’m mentally strong. I’ve got good grounding, I have a good family’; but the attitudes from some within this sport are too political and so damaging.”

A Ferrari not a tractor

Darian was the kind of child who would swim in a puddle.

“She just loved the water,” Carrol said.

It was Darian who believed her destiny was to be a swimmer. Carrol eventually gave into her energetic child’s nagging to take her to the pool and get her “proper swimming lessons” when she was eight. By 10 she was dominating local swimming competitions. At a meet in Bathurst Darian beat a field of boys in the 200m butterfly. All up she won 10 medals.

Her progression was fast. A couple of old state records were smashed. An academic/sports scholarship to a prestigious school was offered. For the kid from the Blue Mountains everything was dreamy.

In 2016, at the age of 15, at the NSW state titles at the Sydney Olympic Park Aquatic Centre she brought home a swag of medals and PBs for every medal-placing swim. Dominating the scene she won all individual medley events, took home silver in the 400m and 200m freestyle and 200m butterfly.

Darian would do anything to be a great swimmer, a self-confessed perfectionist, she would do anything her coach would tell her. Anything.

Darian was a hard trainer, but at her private school squad the natural distance swimmer was coached by a sprint specialist, that’s where some of the first problems arose. She had worked hard before, but this is where she was “flogged”, made to swim sometimes eight kilometres a morning.

“An old coach used to say ‘you’re a Ferrari, not a tractor’, he never flogged me in that way because we worked together perfecting the stroke and flaws,” Darian said. “I didn’t have the muscle or strength of my peers and I am hyper mobile as well.

“So pretty much I was swimming with poor form in the outside lane. You know, the shoulder started to go, every stroke was an 8 out of 10 pain.

“I felt like I was going insane because my coach always told me to ‘stop feeling sorry for myself and that it was all in my head’…”

The pain was “all in her head”; Darian was told this over and over, despite her shoulder being in agony.

Still, in August 2017, she was selected for Swimming Australia’s Australian Talent Identification squad at AIS. The week before she was also at the AIS competing for New South Wales at the State Teams Short Course championships.

But it is here, at the AIS, where her life started to really fall apart.

In the first week of the AIS camp she was recovering from the flu. She could hardly swim. She couldn’t breathe properly. But the NSW coaching officials said to her; “you are being a sook” and “you’ve got to step up”.

In that same week at the AIS she experienced symptoms of her rare illness for the first time. Not that she really understood what it was happening to her. She had been eating watermelon in the AIS dining hall, when all of the sudden, she regurgitated it.

The involuntary regurgitation started happening often at that camp, inexplicably she couldn’t keep down food or drink, and with that Darian’s energy was waning. Still she swam on but struggled. By the second week, the Swimming Australia supervised talent ID camp, she was constantly being lapped by her fellow elite swimmers.

When her coach arrived for the second week of the AIS camp, she saw her and said; “You look like death warmed up … now get back in the pool”. At that moment Darian felt “completely dispensable”.

At breakfast one morning another elite coach remarked; “when are you going to start swimming fast?”

After that her coach pulled her aside again.

“This is what all the other coaches think,” her coach said. “They all think it‘s your mental health. They all think you’re not trying. They all think you are throwing the towel in.”

Rather than refer Darian to a doctor. They said she should see the AIS wellbeing worker.

She remembers sitting poolside with the counsellor, tears streaming down her face. She told the counsellor she was trying her heart out but her body was not letting her swim fast.

“I just can‘t believe how I’m swimming, I’m not coping,” she said to the counsellor. “I want to be here because it’s my dream. I don’t know how to fix it. I don’t know what to do and no one is supporting me.”

And the AIS counsellor’s advice?

“She just took down notes and said; ‘ah, OK, that’s bad’,” Darian said.

The downward spiral

After the camp, Darian’s mum Carrol confronted her coach about their handling of her child’s health at the AIS. The coach was combative. Said all the elite coaches were “disgusted” with her child’s behaviour. “The coach said of Darian; ‘she needs to get her shit together’,” Carrol recalled.

Carrol said; “Well, I want you to let Swimming Australia know that they just needed to speak to the child.”

Carrol considered complaining to Swimming Australia but had been advised by other parents not to bother, because nothing would happen.

“The lack of duty of care shown by Swimming Australia, the AIS and the school; it’s just disgusting,” Carrol said.

“There was no duty of care. This ‘win at all costs’ culture nearly cost my daughter her life. She was completely replaceable. These practices are unprofessional and outdated, something needs to change.”

In the months after that AIS camp Darian was vomiting up to 30 times a day. Darian initially put it all down to stress. She started to withdraw socially and became more depressed.

“She was not the same,” Carrol said.

By February 2018 they were finally able to see a gastroenterologist and she was diagnosed with rumination syndrome.

“The food never makes it to the stomach, and it would sometimes choke me,” Darian said. “I became afraid of eating, and of regurgitating. It is a very isolating illness.”

She trained on through all this but the shoulder injury hadn’t disappeared.

When it became unbearable to lift her arm, her coach relegated her to a lane insisting she swim five kilometres with a kickboard every session. When she could no longer extend her shoulder, she was instructed to wear a snorkel and swim with arms by her side. Darian felt “ditched”. She would cry into her goggles.

“For someone that loves the sport that much and that passion of mine was almost abused,” she said. “I was falling apart, quite obviously. I would walk in the building sometimes crying and the coach would just look at me and say; ‘get in’.”

“The thing that kept me going was probably the fact that I was so good and the fact that I was still, you know, I was so close to an Australian team.”

From the endless laps of kicking her hip became a problem. She “sacrificed” it to keep swimming and later had surgery for a torn labrum in her shoulder.

Physically and emotionally wasting away, the curtain on her swimming career came to a sudden halt after swimming through agony at the 2017 Short Course Open Nationals in Adelaide.

A physiotherapist told Darian to stop swimming because of her shoulder. She tried to pull out of a school swim meet training day.

“I don’t care,” said her coach. “You are going to get into this relay and you can swim with your bloody arm beside you.”

Darian did what the coach told her to do.

“Our team came last by a mile and everyone was just watching me … I felt like an absolute fool,” she said. “It was like, you know, the higher you climb, the harder you fall.”

Fighting back

In the next two years Darian would face the fight of life.

She was too ill to return to school. She completed her HSC in hospital. Her heart would almost stop beating. She considered suicide. “I had to learn how to eat again, walk again” she said. It was a huge burden on the family both financially and emotionally. It affected everything.

All the while she was dealing with PTSD from her time in swimming. She would get flashbacks of horror training sessions.

“I would start hyperventilating and screaming and mum would have to hold me because I‘d start scratching myself and trying to rip out my hair and hurt myself,” Darian said.

“If I just thought about swimming, I would go into that state. Even if I saw a pool, I would have nightmares every single night. They tried to put me on all kinds of medication to fix that because I would wake up in that kind of PTSD state because I‘d been dreaming about it all night and then it would ruin my whole day.”

While her peers from that AIS team camp qualified for the Olympics this week, Darian reflected on piecing her life together. She was proud of her resilience to fight back from the edge of death.

“I do think ‘what if’ … instead I have spent years trying to rebuild my life, learning to walk again, learning to eat again. But yeah, I’ve done it,” Darian said.

“I didn‘t think I’d be able to swim again or ever eat my favourite foods again or ever fall in love or ever, you know, have friends or go out, but I have now, and I am proud of my recovery.’

“By telling my story I want to protect others, there is no justice for me. I couldn’t wish worse on anyone, not even my coach. The amount of suffering I endured could have been prevented with some simple care and I know I’m not the only one to have been victim to this kind of abuse.”

Need help? Call Lifeline on 13 11 14

Olympian to revive national career after Paris drug bust

Banned Kookaburra Tom Craig is set for a return to the national team and has spoken out for the first time since his Paris Olympics drug bust, revealing that he feared his career was over.

‘Not a bikini?’: Anger over runner’s briefs

A 31-year-old who recently competed her first marathon has responded to critics of her outfit, asking: “Should I have worn a tracksuit?”