‘A raffle’: Why experts say gender testing at the Olympics is a dangerous route

It’s the topic which has been the most talked about of this year’s games – and it all started with one Australian city.

Olympics

Don't miss out on the headlines from Olympics. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ANALYSIS

The gender debate surrounding the Olympics has spiralled so far out of control it’s easy to forget that there are two athletes, on the biggest stage of their careers, at the centre of it all.

It’s also hard to get the facts, and for that, you can thank the International Boxing Association (IBA).

To get those, we need to go back into the history books a little.

Both Algeria’s Imane Khelif and Taiwan’s Lin Yu-ting, who have been at the centre of this controversy for weeks now, have made it to the finals.

Khelif took the gold on Saturday morning AEST.

So what better time than now to turn the pages?

Eligibility testing across the Olympics

Gender testing in the Olympics is nothing new. Each sport’s governing body is responsible for drafting its own eligibility rules, and gender and the IOC accepts the age and gender of athletes on their passports.

Testing has only come back into the discussion due to the IBA’s decision to test athletes before the sport’s 2023 World Championships.

Both Yu-ting and Khelif – who identify as females, were assigned females at birth, lived as females their entire lives and have always competed as females – failed the testing despite having boxed for years.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) called the decision to test the athletes before the championship “sudden and arbitrary”.

IBA chief executive Chris Roberts said XY chromosomes were found in “both cases”. In most cases, the female is XX, and the male is XY.

However, the IBA has refused to go into further deal about how it reached that conclusion, citing privacy reasons.

The IOC, however, doesn’t gender test anymore. So that’s what has landed us into the entire circus.

Should those with XY chromosomes be able to fight in the women’s category?

These tests result show that Yu-ting and Khelif are both people with innate variations of sex characteristics.

The IOC says it is fine for the athletes to compete in female category given that – once again - they identify as females, were assigned female at birth, lived as females their entire lives and have always competed as females.

Both competed in Tokyo. They didn’t win a medal.

So that should be the end of it right?

Sadly, no.

The IOC mandated gender verification for female athletes in 1968 until 1998.

In fact, our very own 2000 Sydney Games decided to abandon it.

And why?

Well first – the testing was expensive.

It costs around $150,000 to conduct the testing – and this didn’t include volunteers’ time which was given by around 60 professionals over up to 90 days.

Secondly, it also put the athletes under more stress at a time when there was already so much pressure.

And thirdly, given the absence of males trying to “masquerade” as females to compete, the IOC decided to do away with it moving forward.

But as pressure continues to mount for the IOC to bring the testing back, experts have warned there is a very important fourth reason why the testing should be abandoned.

“It could be a bit of a raffle,” Sydney Health Ethics Associate Professor Morgan Carpenter says.

“There are people that don’t know, there are people that are not told [they have any variations of sex].”

On top of this, Prof Carpenter, who runs a project on models of care for people with innate variations of sex characteristics, says that people who have any ambiguity to their sex can express it prenatally, in puberty, while trying to conceive a child or during menstruation.

But for most elite athletes, menstruation and puberty look quite different to the average person – adding another layer of complexity.

Crunching the numbers

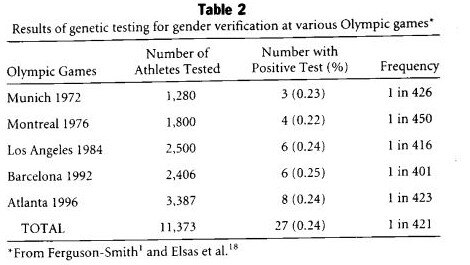

At the 1996 Atlanta Olympics – the Games before the testing was abandoned – 3387 female athletes were tested. Eight of them returned a positive result for the SRY gene which is found on the Y chromosome - or one in 423.

In Barcelona 1992, 2406 were tested, and six returned positive. In Los Angeles 1984, 2500, six were positive.

Across five games, 11373 female athletes were tested with 27 returning positive results.

That works out to about one in 421.

Given there were 5503 female athletes at the Paris Olympics – statistically, that would mean roughly 13 women would have innate variations of sex characteristics.

Statistically, Prof Carpenter says, it could be any of the Olympian champions from any nation.

What if all of sudden – one of the Olympic stars of the last few Games suddenly found out that they too had innate variations of sex characteristics?

Prof Carpenter says it is more than possible.

“Disclosure is still a problem, including in high-income countries, including in countries like Australia and New Zealand,” he said.

“Historically, and the evidence suggests that this is still sometimes the case, individuals with innate variations of sex characteristics are not informed that they have a variation.

“Some doctors still believe it’s too stigmatising to know. And seeing how demonised people are in the public space … it lends a bit of weight to that hey?”

Respect above all

Prof Carpenter said he hopes for a more respectful future for Olympians with innate variations of sex characteristics.

The conversation around Khelif and Yu-ting – especially online – has been nothing short of abhorrent.

“There is a percentage of people, a very small percentage of people, whose bodies are a bit different, but who still have the same rights to compete and have the right to compete in their birth, assigned birth, observed sex,” he said.

“If somebody has been observed assigned female at birth, has lived their life as a woman, understands themselves as a woman, then who has the right to take that away?”

Yu-ting’s gold-medal bout in the women’s featherweight division starts on Sunday August 11 at 5.30am.

Originally published as ‘A raffle’: Why experts say gender testing at the Olympics is a dangerous route