1989 Canberra v Balmain rugby league grand final: what happened as the game went into overtime

IN the final instalment of our countdown to the 25th anniversary of NRL’s greatest grand final, we reveal what really happened as the epic encounter went into overtime.

IN the final instalment of our countdown to commemorate the 25th anniversary of rugby league’s greatest grand final, we reveal what really happened on the field as the epic encounter charged into overtime.

With17 minutes to go, Balmain won the scrum and took the ball to the right side of the ground. Scheming halfback Gary Freeman was calling the plays and scanning the field _ he looked right, straight, left. Hang on. Left. What’s that? Bingo. He’d spotted it. All game he’d been waiting and finally there it was. Meninga was isolated.

“Take one in and then a ‘Crash’ on me,” he yelled. He got replies from a number of his team-mates which meant they had all claimed the necessary roles for the move to work.

Steve Edmed took “one in” and was tackled about 10 metres from the Canberra try line right in front of the goalposts. He played the ball and, like the wheels of a clock clicking over, five Balmain runners on different parts of the paddock set in motion. Elias speared the ball from dummy half to Roach who appeared to be making a solo run straight at the Raiders defence line.

“He had no intention of just running straight,” Garry Jack reveals. “He was just the first part of the play.”

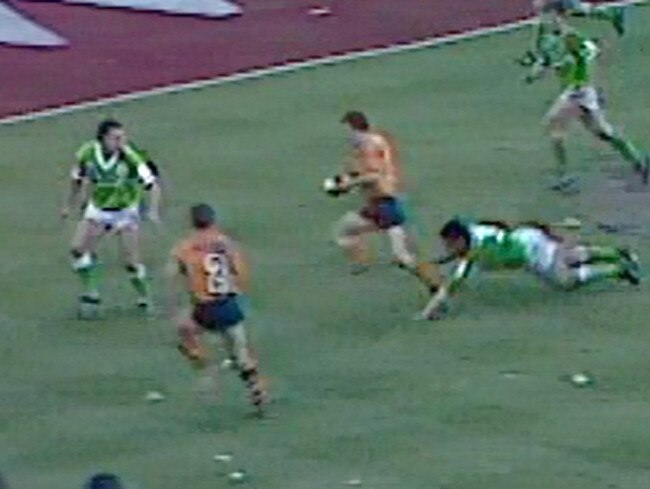

As Roach was about to be tackled he turned away from the Canberra defence and passed to Freeman who was sweeping across from the right hand side of the field. Roach had drawn two defenders who were now locked in to tackling him even though he didn’t have the ball. As Freeman ran parallel to the try line Bruce McGuire loomed on his left with Garry Jack in support. Wider out was livewire five-eighth Mick Neil who had been hovering around the middle of the field before sprinting out wide to be the extra man.

On the defensive line Meninga could see Freeman coming across and also McGuire on the charge. Instinct told him to creep in and help his team-mates contain the Balmain runners. But then something caught his eye that made his spine go cold.

Commentator Graeme Hughes saw it too. But it happened so quickly he could only scream out one word: “NEILLLLLL!”

By taking one step to his left Meninga had created a hole to his right. And at that moment the ever-reliable Mick Neil, a player with the physique of a coat-hanger, had got around the mighty Mal Meninga.

“I saw it and I felt it,” Meninga recalls. “And I had to react as quickly as I could because I was beaten cold.”

And he did react. He lunged backwards and to the right, flicking his hand towards the flying legs of Neil and, somehow, pulling off the most famous ankle tap of all time.

“I knew the ball went past me,” he says. “My reaction was ‘hang on, hang on they’ve got me, they’ve got me cold, but if I do something special here it just might stop them (from scoring a try)’. So I dove. If it were anybody bigger than Mick Neil then maybe they would have scored. But because I tapped him pretty solidly _ and I guess because of his size _ I imagine that’s the reason the try was stopped.

“It was a moment. A moment of utter relief because that was the game.”

PART 1: Secrets of the greatest NRL grand final

PART 2: The hits that rocked the 1989 grand final

PART 3: How a penalty changed the game

Neil tumbled to the ground a metre out from the Canberra line. Before he could get up and reach over to score, Canberra hooker Steve Walters pounced on him like a tarantula.

On the very next play Meninga’s great rival Wayne Pearce also felt the cold rush of grief go through him. Neil played the ball and Balmain threw it right. The Tigers had an overlap. Freeman fired the ball to Roach, who swung it to Elias, who lobbed a high pass towards Pearce. The Balmain skipper snatched at what he thought was the ball, but it was really just a blur as it was coming towards him from his left _ the side of his detached retina. He knocked on and the opportunity was lost. The whole stadium appeared to deflate as more than 40,000 hysterical fans let out a breath. On Pearce’s right in support stood Tim Brasher and James Grant. The only Canberra defender in their way was Laurie Daley.

Pearce screamed to the sky in frustration. Two chances in 30 seconds gone forever.

“Yep, it was my left hand side,” Pearce laments. “My left eye was constantly blurred from the detached retina. I always struggled catching balls from that side, especially high balls. Just trying to focus on them. Look, I’m not sure if we would have scored but it was definitely an opportunity that slipped.”

Standing on the right hand wing, James Grant had been following the ball as it came towards his side of the field. He was also aware of the open space in front of him.

“I remember thinking to myself ‘I’m in for three here. This is the third try I’ll be involved in today’,” he says 25 years later. “I was that confident. But the ball Junior got was a floaty type ball. A real tough pass.

“Look, I want to be clear. There’s no way in the world I want to blame Junior in any way, he’s the world’s greatest player and won so many games for us. I’ve dropped plenty of balls and missed plenty of tackles. But I had no one outside me and had 20 metres to go (to the line). At the very, very worst I would have made the corner in a jog.”

As the mayhem continued on the field a major decision was being made in the stands. To win the game, Balmain coach Warren Ryan believed he had to save it. With 15 minutes to go and the Tigers leading 12-8 the two-time premiership mentor believed it was time to replace his enforcer, Steve Roach.

With a scrum about to pack down on the far side of the field, Kevin Hardwick, a tackling machine and trusted Balmain servant, jogged across the ground to swap places with big Blocker. Roach was stunned. Then he started seething.

Bill Harrigan, who was standing in the middle of the two packs, remembers the tension.

“He didn’t want to go,” Harrigan recalls. “He said ‘No, get f***ed, I’m not going’. And I think I said ‘mate, we’re not playing until you do. You’re being replaced’. I had to call time off. Blocker was absolutely filthy.”

As Hardwick confirmed to his furious team-mate that his time had come, Roach slapped his hand and started a long angry walk back to the bench. Twelve months beforehand Balmain had flown Roach around the world to try and qualify him for a grand final. A year later Ryan couldn’t get him off the field quick enough.

The debate about Ryan’s decision continues 25 years later with no one taking a backward step. In his book Doing My Block Roach says: “I was filthy on everyone when I was replaced. I just couldn’t believe it. I was too angry to think straight. The only thing going through my head was, ‘Why did he do it?’. I’m still asking myself the same question years later.”

He adds: “All I know is that if footballers have a heaven I’ll walk in with a clear conscience about the 1989 grand final. Other people might have a bit of explaining to do.”

After the match Ryan was quoted as saying: “We were leading … and the natural thing to do with about 15 minutes to go was to start taking off your big blokes who aren’t going to help you in defence. They are going to be your worst defenders because they are tiring and can’t get back into the line quickly enough.

“That’s why, when you are defending a lead in a grand final, you want the best and the busiest defenders you can find.”

And defend is what Kevin Hardwicke did. He just kept tackling. And so did his team-mates. All across the park. Whether it was Steve Edmed in the front row or Steve O’Brien on the left wing, the Tigers just kept turning up. Their sustained, suffocating defence looked like it had squeezed the last breath out of the brilliant Raiders’ backline.

And then the men in black and gold found some luck. Canberra were pinged for being offside and a Currier penalty goal put Balmain in the box seat. They snuck out to a 14-8 lead meaning the Raiders would need a converted try just to catch them. With less than 10 minutes to go the Tigers appeared safe.

They were also playing panic-free football. As the clock ticked over to signal six minutes and 45 seconds until fulltime Balmain were back near the Canberra goal posts. Benny Elias fired off a field goal attempt but Meninga came charging at him and blocked the ball as it came off Benny’s boot.

Despite the Canberra captain’s effort, possession went back to the Tigers and Elias prepared himself for another shot at glory. One point would put Balmain out of reach. All he needed to do was fire that football over the posts and the Tigers would triumph for the first time since 1969. History was a heartbeat away.

Bruce McGuire took a hit up and was tackled in the middle of the field, less than 10 metres from Canberra’s try line. Gary Freeman raced to dummy half and speared the ball back to Elias who was 15 metres out and directly in front of the goal posts. He couldn’t have been in a better spot. The plucky hooker set himself, aimed and drop-kicked the ball. He’d struck it as sweetly as a golfer hits a perfect five iron _ straight and hard. He watched it head towards the black mark painted in the middle of the cross bar. His team-mates looked on in hope. The Canberra players followed the ball with dread. Millions of supporters held their breath. Then they all heard a sound.

“THWACK!”

The ball hit the crossbar! A slither of wood 20 centimetres high. The difference between glory and gloom.

Commentator Graeme Hughes screamed out what everyone else was thinking: “WHAT ELSE CAN HAPPEN!?”

Elias still shakes his head 25 years later.

“What can you say,” he says. “If I’d been an inch taller or connected with it half a second earlier it floats over. It just wasn’t meant to be.”

With less than five minutes until fulltime Canberra worked the ball forward until they ran out of tackles and a scrum was put down near the halfway line.

Trotting back to his position on the left wing, Steve O’Brien caught sight of some commotion near the entrance to the tunnel at halfway. NSWRL boss John Quayle and other officials were assembling with the Winfield Cup trophy, obviously preparing for the presentation after the match.

O’Brien couldn’t help himself.

“Hey Brash,” he yelled out to Tim Brasher, his teenage team-mate. “Have a look at this. We’re about to become premiers.”

But, as both sides had learnt that day, there are two things you can’t trust on a football field - the bounce of a ball and the referee.

From the scrum Bill Harrigan blew his whistle to penalise the Balmain backs for being offside. It was an infringement he, nor any other referee, had found fault with during the final series. And it meant the match was far from over.

Canberra started their attacking raids going to the right side of the field. Then they swung the ball back to the left. On the fourth tackle a Ricky Stuart chip kick was touched by Balmain giving the Raiders six more tackles. Once again they flung the ball from sideline to sideline with Clyde, Meninga and Daley all unsuccessfully trying to break through the Balmain defence.

Finally it was their last tackle just 10 metres out from the Tigers’ try line. With 90 seconds left on the clock, five-eighth Chris O’Sullivan jumped into dummy half and punted a towering kick into the air. As it came down near the goal posts Garry Jack, Andy Currier and Canberra’s “super sub” Steve Jackson jostled for the ball. It bounced clear into the arms of Laurie Daley who hoicked it over his head to John Ferguson.

On Ferguson’s left was the far corner post, but he could see the Balmain cover defence sprinting across to catch him. So the 35-year-old livewire winger decided to head back in-field and rely on a jinking step that had sliced through opposing teams for 10 years. Four times he pushed off his left foot leaving a quartet of Tiger tacklers in his wake. Then, with Steve Jackson pushing him from behind, he ducked under the giant frame of Paul Sironen and planted the ball over the try line. He had done it. Canberra were back in the game. It was 14-12 with a conversion to come.

Garry Jack still wonders what might have been.

“Maybe I should have called for the ball a bit louder,” he says. “I went up for the ball like I always did, with my right knee forward and my hands on my chest. I was watching the ball as it came into my chest but then Andy (Currier) came in a bit too close and the Canberra guy (Jackson) was there too …

“I’ve also wondered since if I should have tried to take it with my hands in the air like an AFL mark instead of on my chest. But that’s all in hindsight.”

As the Canberra players celebrated, Wayne Pearce and his men stood behind their try line in shock. Hunched over and hollow-eyed they looked as if any signs of life had been drained out of them. Meanwhile, Mal Meninga raced to get the ball. He knew he had to kick this goal to equal the scores and didn’t want anything distracting him.

“There was no excitement from me to be honest,” he says. “I just wanted to get the ball as quickly as possible and kick that goal. I didn’t want to mull over it. A quality kicker should kick that goal. That was my role and that’s what I should do.

“They’re the moments you live for. It’s not as if you turn up on the day and kick a goal to draw the grand final, you live for those moments and you’ve been doing it for 10 odd years so I knew how to handle that situation.”

And handle it he did. The ball sailed straight between the posts. The scores were now locked at 14-all and Canberra had the momentum of a tidal wave. What’s more, Balmain strike forward Paul Sironen was walking off the field after been replaced by tackling specialist Michael Pobjie. The Tigers now had their two power forwards watching from the sideline.

Within seconds the fulltime siren screamed out across the stadium. But, what was supposed to be the end was now the start. For the first time since 1978 a grand final would be going into extra time. As Tigers winger Steve O’Brien said so poetically in the dressing room afterwards: “For 78–and-a-half minutes the man upstairs wore black and gold. Then he swapped sides.”

For the following few seconds it seemed as if no one knew exactly what to do. It was like a photo finish in the Melbourne Cup. The race had been a thriller but there was still no winner. The players wandered around the field in a bit of a daze; the crowd buzzed and chattered with excitement; referee Bill Harrigan looked towards the tunnel for direction.

But one man with a plan was Canberra coach Tim Sheens. He’d made his way down from the Members Stand to the sideline to speak to his halfback general Ricky Stuart.

“You’ve got to kick early and kick deep,” he said. “They’re exhausted. Play it down their end of the ground and the mistakes will come.”

Out on the field the two teams had changed ends. Wayne Pearce, who knew the tackling his team had done had taken its toll, told his troops they just had to keep fighting. “This is life or death stuff guys,” he urged. “We’ve all just got to dig in.”

In the other huddle Stuart let Meninga know of Sheens’ instructions. Then, from out of nowhere, replacement prop Steve Jackson spoke up.

“We were all tight, all in there together and I remember pulling my head out and having a look at Balmain and they were like Brown’s cows,” Jackson recalls. “They were scattered all over the place. I said “have a look at them, they’re all over the joint! They’ve lost it!”

“I remember it. I get a bit loud sometimes and, you know, in that kind of situation you try not to say too much but I remember saying “have a look at them. We’ve got this boys, we’ve got this!”

Mal Meninga kicked off the first 10-minute half of extra time and, once again, Garry Jack caught the ball. For the 28th time that afternoon the snowy-haired fullback sped towards the oncoming defence. This time Canberra centre Laurie Daley was able to wrap him up but, as he did, Jack felt an electric current of pain jolt through his right hand. ‘Arrgghhhh,” he winced to himself. He looked down to see his middle finger bent back towards his wrist. It was dislocated.

He played the ball quickly and called out to the trainer for help. The pair stood behind the action pulling and jerking at his painful digit doing whatever they could to slip it into its socket. But, no matter what they tried, they couldn’t snap it back into place. Having broken his right arm earlier that year Jack, like Meninga, played with a heavy guard protecting his limb. Now a finger on the same arm was as crooked as a grape vine. He would have to battle on.

Canberra soon had possession and, on the fourth tackle, Ricky Stuart launched a towering torpedo kick towards the clouds. The crowd watched in awe as the ball spiralled skywards, spinning through the air, whistling in the wind until it peaked. Then, it dropped, plummeting like a piano falling out of a building in a cartoon. Its shadow loomed larger and larger over the lonely figure of Garry Jack who was guarding his goalposts and hoping to guide the ball into his one good arm. He caught it. Then, unbelievably, it trickled out and rolled onto the ground in front of him. A knock on. His shoulders slumped and he looked as if he would break into a thousand tiny pieces. Canberra would now have a scrum feed 15 metres out from Balmain’s try line.

“I’ve never really told anyone about the finger, you don’t want to make excuses, but with my finger sticking out and the arm guard on … yeah, it didn’t help,” Jack laments 25 years later.

Running downfield Raiders five-eight Chris O’Sullivan yelled out to Stuart to give him the ball when they won the scrum. He was going to go for a field goal.

Stuart couldn’t believe it. Neither could Meninga.

“That field goal wasn’t under my direction,” Meninga says. “We were running to the scrum and he said ‘I’m going to kick a field goal’ and I said ‘no, we’re going to control it’ and he fired back ‘nup, I’m kicking a field goal’. By that stage I just said ‘well, do what you f***ing want then’.

“Chris was a strong-headed and strong-willed person and if he was determined to do something, then I let him do it.”

The Raiders won the scrum and Stuart rocketed the ball to O’Sullivan who slotted a field goal over the black dot. He hit it so hard it went hurtling into the crowd. Finally, after more than 80 minutes, Canberra were in front. And that edge actually made a difference.

“Chris kicked it, but there was still a long time to go,” Meninga says. “That’s why I was against it. I wanted to get field position. But in reality and in hindsight it deflated the Tigers because we hit the front for the first time.”

Belcher was also against the move.

“To be honest I thought it was a really selfish play,” Belcher says. “It wasn’t the right play. Not at 14-14 when you’re going to go 10 minutes each way. It wasn’t golden point back then. We were going 10 minutes each way and we were only two or three minutes into extra time. We should have played six tackles at Balmain and scored.”

But, being behind by a point after leading all game had psychologically broken the Tigers.

Looking on from the sideline Paul Sironen thought he was “watching a car accident in slow motion. I was just thinking ‘how can it be turning out like this? This isn’t supposed to happen’.”

James Grant remembers feeling “dead on my feet” after the field goal. “We kept at it but the game was gone by then.”

The Tigers did keep at it. Five minutes into the second half of extra time Pearce made a break down the centre of the field before passing to Tim Brasher who galloped clear. But, as the crowd rose from their seats in hope, the Canberra cover defence cut him down.

With three minutes to go Balmain’s enigmatic English centre Andy Currier decided to gamble for glory, attempting a grubber kick on his own quarter line. The ball dribbled off his boot and into the arms of Meninga, who looked up to see the Tiger try line just 25 metres away. He began his charge but had teenage centre Tim Brasher hanging off his sleeve so he slipped the ball to a team-mate on his left. That man was Steve Jackson. And the burly, 23-year-old Queenslander, who was the last man picked for Canberra, remembers every moment of what happened next.

“Mal gave me the ball,” he says 25 years later. “There was less than three minutes to go and I knew it was out first tackle. I knew we were one point in front and as soon as I caught the ball I automatically thought ‘don’t pass it, don’t make a mistake, just run’.”

And run he did. First he went to the left where he stepped around replacement pivot Shaun Edwards. Then, when he saw Garry Jack coming over in cover defence, he went back to the right forcing Jack to stop and dive at his legs, but he slipped off _ “yep, I went too low on him,” Jack admits.

But Jack’s attempted tackle spun the big prop around which meant Mick Neil struggled to grip Jackson’s jumper so the red-haired five-eighth fell off just as Jackson trampled over Shaun Edwards, who had come back for another go at the rampaging Raider. Jackson had now taken 20 steps, the same number he wore on his back. Stumbling forward he lurched for the line but clashed heads with Kevin Hardwick. He brushed that aside to reach his left arm over the try line just as Balmain halfback Gary Freeman tried to punch the ball clear.

Phew! He had made it. With the job done he dropped his head onto the grass, overwhelmed and exhausted. Behind him lay a trail of destruction as bodies and broken Balmain dreams were left scattered in his wake.

“The last thing I was thinking of was scoring a try,” Jackson says. “All I was focussed on was ‘don’t make a mistake’.

“I remember hitting, doing a spin and hitting heads with Hardwick.

“It happened so slowly. You watch it and it seems so quick but it happened so slowly and I remember thinking ‘f***, there’s the try line, if you can put this ball down you’ve scored a try in the grand final’.

“When I looked up, Bill Harrigan was standing there with his arm pointing straight at me and I remember putting my head down and thinking ‘I made it, I made it, I made it’ and I was stuffed!”

The Raiders now led 19-14 and 90 seconds later the final siren signalled a new chapter in the rugby league history books. Not only was it acknowledged as the greatest grand final ever played, it was also the first time a side had won a premiership from fourth place. Canberra also became the first team to win from outside of Sydney. And their come-from-behind victory meant they’d clawed back the biggest half-time deficit in a grand final.

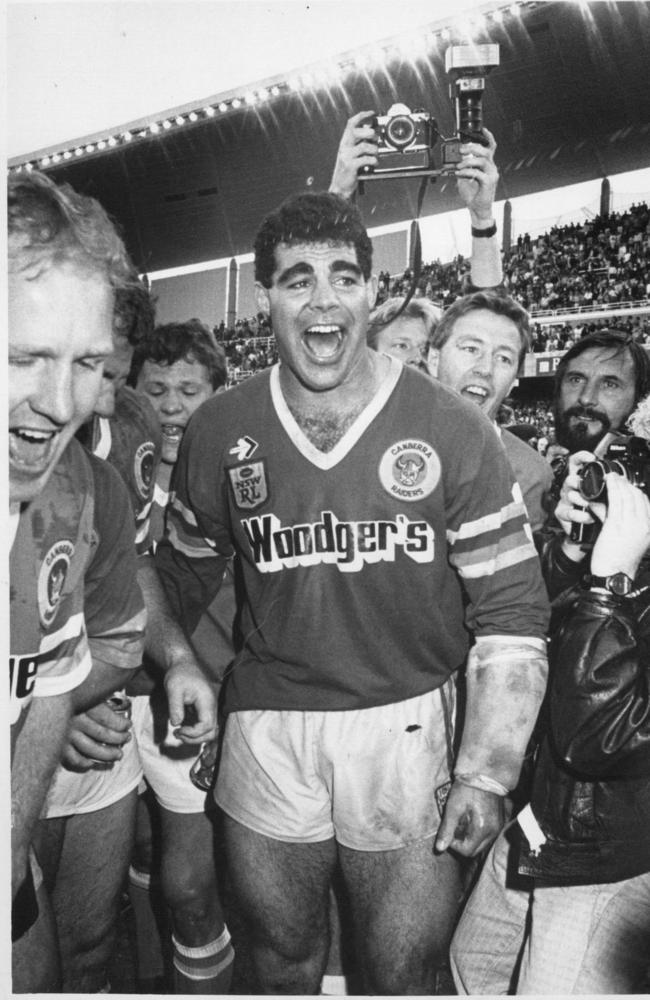

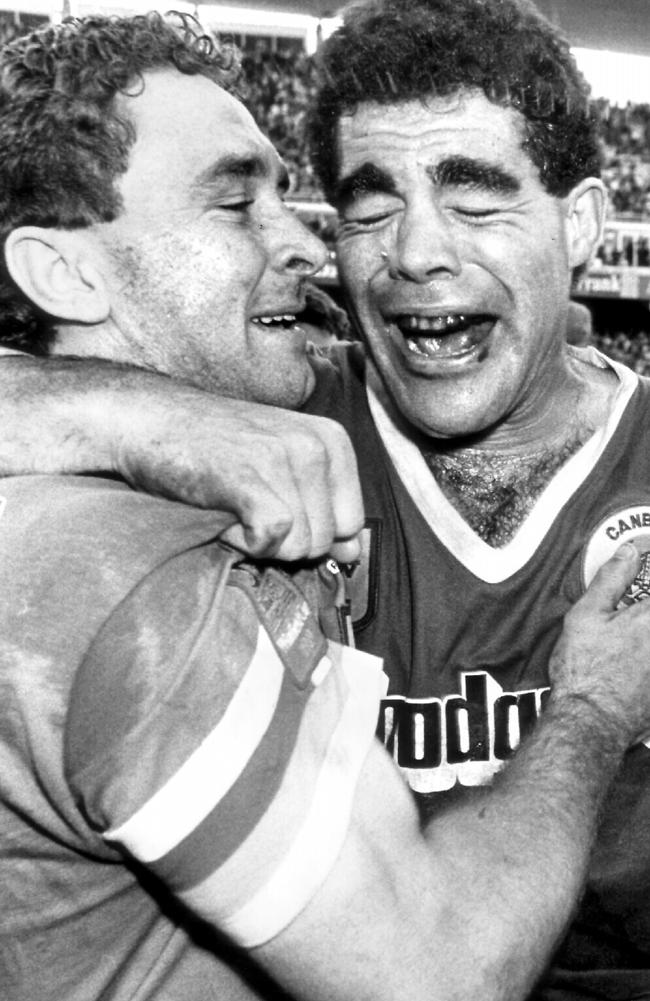

The enormity of the achievement was best captured in Meninga’s reaction at fulltime. From the start of the day the only expression that cracked his face had been a growl or a glare. Now he was overcome with emotion, crying openly, shoulders shaking as he sobbed into the arms of his team-mates.

“It was the most emotional I’d ever been and I broke down and cried and I’m not ashamed of that,” Meninga admits. “It all poured out. It was the highlight of my football life.

“For me it was also liberating. From a selfish point of view it was a moment in my footy career that enabled me to stand on a pedestal and say ‘well, I’ve done it’. It was on the back end of four broken arms and, as a Queenslander, you never really get that recognition in the toughest competition in the world until you actually achieve something in Sydney.

“For the team, the win was a reward for all the hard work you go through together with your mates. There is no better feeling. That game still bonds us today. We will never lose that bond.”

Scattered across the oval, as if they’d been tossed from a truck, were the Balmain players. Many were unable to move. Some were sitting with their heads in their hands, other lay face down in the dirt. Pearce, Sironen, Roach, Jack and Elias all admitted crying tears of despair.

Pearce was emotionally and physically broken.

“To be honest, at the end of that game I was the most fatigued and tired I’d ever felt,” he says. “And that includes State of Origin and Test matches. I was really struggled to lift my legs off the ground to walk. That’s how tired I was.

“I cried after that match, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. It just all became too much.”

The Raiders’ 1989 success was the start of a golden era for the ‘Green Machine’. They won the premiership again in 1990, finished second in 1991 and won another title in 1994. The 1994 grand final was Meninga’s farewell match meaning he retired on an ultimate high as a premiership-winning captain.

Wayne Pearce’s career came to an earlier close. After battling through 10 games in 1990 he was forced to retire after his knees could no longer cope.

History would be cruel to the Tigers. Of the 13 players to start the match, only Steve O’Brien knew what it like to win a grand final having been on the wing for Canterbury in the 1984 premiership team. None of the other Balmain players who took part in the 1989 decider - the greatest grand final in rugby league history - would ever win a premiership.