Paul Kent: Why salary cap mismanagement is the reason for NRL blowout scores

Until clubs figure out why players switch clubs, they will continue to overpay for talent and salary caps and scorelines will continue to be blown out, PAUL KENT writes.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

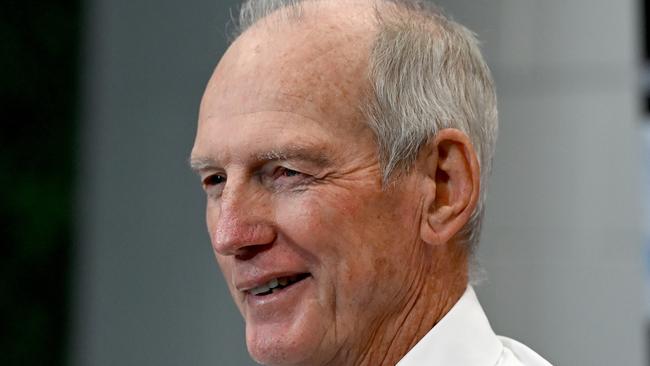

Call it old habits, but I often find myself agreeing with Wayne Bennett even though I no longer talk to him, which balances nicely with Buzz because I talk to him regularly but don’t often agree with him.

Yet as of today, a Tuesday in 2021, we all find ourselves in agreement. The Three Amigos.

It might be time for a Covid check.

Bennett was not buying the line on Sunday afternoon that the rule changes are responsible for the score blowouts that have so many people moaning in the game at the moment.

Watch The 2021 NRL Telstra Premiership Live & On-Demand on Kayo. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >

Three Saturday floggings, with a combined points differential of 146, seemed to wipe from memory the two one-point deciders played Friday night and suddenly the sky was falling in.

Then along came Bennett, who is still good for the odd quote and an old-timer’s sense of perspective.

Bennett looked at the cause, not the symptom.

“Management of clubs has a huge result on performances at the moment,” he said after his Rabbitohs gave it to the Tigers, 38-22.

“Clubs have got to take a hell of a lot more responsibility than they are taking for the way the game is being played.

“It’s as simple as that.”

Some years back, when the Commission-era was born, the game went through what some believed was its Intellectual Revolution. That was the first sign people should have been nervous.

In one of his first meetings incoming chairman John Grant, a dot.com millionaire, gathered the clubs and told them all, clearly a bunch of knuckleheads, that the Commission was going to show them how to make money.

The club bosses nodded meekly, beaten into submission that the game needed more business people involved to break from the doldrums of clubs continually battling to break even.

Not all, though.

“This’ll be good,” said Roosters boss Nick Politis, who built a car yard in the eastern suburbs into a $1.3 billion empire that spreads across the world but for 40 years has also overseen the game’s struggles to make clubs’ profitable.

Suddenly, with this new narrative from head office, the new standard was to invite successful business people, and some not so successful, to the board of a football club even though they had no industry expertise and could not tell the difference between a football and a pineapple without considerable guidance.

It was a disaster, and the game feebly allowed it to happen because this is what they had been taught to believe.

These people were swallowed up by their naivety.

Of course it finally collapsed and Grant was one of the casualties, ousted from the Commission, as the smart clubs realised they don’t need people who know football on their board, as they once had, or people who know business, as they were being told, but people who know the business of football.

Running football clubs requires industry expertise.

But to Bennett’s point, too many clubs still don’t know what they are doing, and still bluff that they do.

They fumble from one disaster to the next, trying to copy what Melbourne do, and more lately the Roosters, hoping they will fluke upon success.

Any individuality has disappeared.

Mistakes in recruitment are replaced with mistakes in recruitment.

The latest necessary weapon has been the need to build high performance centres, the greatest waste of government money since they decided to put Bradford Batts in everybody’s roof.

At the football level these clubs convince each other they are doing best practice even though they have no idea what it looks like, but they get away with it because those overseeing them also don’t know what it looks like so they can’t call them on it.

All they can do is rotate through the player market hoping they might fluke it.

Spending the salary cap because they have to spend it, without ever realising what value for money looks like.

There is also a false salary cap that operates in the game but too few clubs realise it.

How can Canterbury spend $9.02 million on players, the same as Melbourne?

The clear example of the bias in the cap is the Bulldogs do not have one player on minimum wage.

Nick Meaney is on good money at the Bulldogs but was offered close to minimum wage to remain, where the Dogs believe he represented fair value.

Melbourne also thought he offered fair value at near enough to minimum wage. So Meaney has signed with the Storm.

The bias in the cap means the Bulldogs have to pay more to sign a player to their club than successful clubs like Melbourne, who can afford to offer less than market value because the club has so many other attractions.

Recently the RLPA surveyed 480 players on the reasons why they switched clubs.

About 70 per cent, 380 of them, said money was not the chief reason.

Their reasons ranged from family, to seeking a better high performance environment, to a coaching relationship, to giving themselves a better chance to win a premiership, to their development as a player.

That would support Bennett’s statement.

And until clubs figure it out, it will always remain.