Coddled NRL players unable to cope with pressure outside footy bubble

Instead of being protected from adversity and ill-prepared to handle setbacks, modern NRL players need education and exposure to the realities of life and accountability, writes PAUL KENT.

Brad Arthur spoke to a generation of PlayStation footballers last weekend.

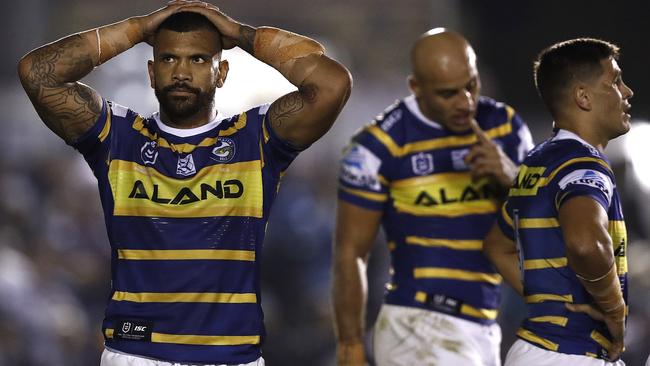

“We’ve got to be full-time footballers every week, not part-time,” Arthur said of his Parramatta Eels.

He was talking about a team of hardened professionals who, already trailing 14-6, clocked off and let in 24 points over 22 minutes to murder any chance they had to win.

Arthur was having none of the excuse offered afterwards, that the loss of captain Clint Gutherson knocked the Eels from their game plan.

Gutherson was gone half an hour earlier.

What was missing was effort. The kind of effort professionals are employed to do.

Professional footballer is a misunderstood term in the modern game.

Nowadays, it seems to mean a week at home kicking back on Fortnite and planning Saturday night with the boys because it’s an away game, with a little footy thrown in to pay the bills.

And if things don’t go right in the only way that matters for the fans, that they actually lose the game, well, you just don’t understand the pressure of being an NRL player.

In the same week that Parramatta texted through their effort against Cronulla Ash Taylor walked into Gold Coast headquarters and asked for extended leave.

Taylor is 24 and earning $1 million a season to play for the Gold Coast. He made no offer to his employer to deduct his pay for work not done, which is common in the real world when an employee asks for indefinite leave.

Taylor’s bad habits have been part of the NRL dialogue since certainly the off-season.

Most are self-inflicted while others are the kinds of problems we all encounter in life and yet still have to get out of bed each day and get on with an honest day’s work. We might not be at our best but we give our best.

In the same week Taylor sought leave Titans head of performance and culture Mal Meninga also revealed that Tyrone Peachey is suffering home sickness and they have had a conversation about him returning to Penrith, just half a season into his three-year contract.

“Family comes first,” Meninga said, leaving it open for a deal.

Men will move across the country to take a job in the mines for a pay rise. There were times when family would sacrifice, together, for a better future.

Nowadays, everybody wants comfortable suffering. Adversity must be acceptable.

Many of Taylor’s problems could have been headed off if someone was willing to have the tough conversation with him earlier.

Instead, a culture of apology drives the NRL.

When Taylor waddled through last season overweight and out of form many rightfully questioned the weight he was carrying and its effect on his form.

His club was quick to defend him, claiming weight was not a problem.

Only when Taylor began this season having finally lost the weight was it finally OK to address the elephant at the buffet.

“The biggest thing is to make sure I am fit and healthy enough to ensure I am playing for that full 80 minutes and not fading out of games,” Taylor told NRL.com before the season, revealing he had stripped six kilograms over the summer.

Apparently it was acceptable to speak of his weight only once it was on favourable terms.

Buoyed by the praise, Taylor spoke of his new-found application at the Titans.

“You get injuries and you think ‘it will be all right’ but this year I am looking after all my bumps and bruises and preparing like I am getting ready for a game each time I go to training,” he said.

Would we be so forgiving if someone else in a high pressure job, a surgeon about to operate on your heart, had such a laid-back approach to their job?

This, from a young man being paid $1 million a year.

There is not a job in the country where somebody is paid $1 million a year and it does not involve pressure.

Yet in the NRL every indulgence is made to remove the impediments to performance, without the realisation it softens the underbelly.

Instead of being protected from adversity and ill-prepared to handle setbacks when they arrive the young men in the NRL should be educated, exposed to the broader realities of life and accountability, like athletes around the world.

Professionalism is not a sometime thing.

Heart surgeons don’t get to say they “just didn’t turn up”.