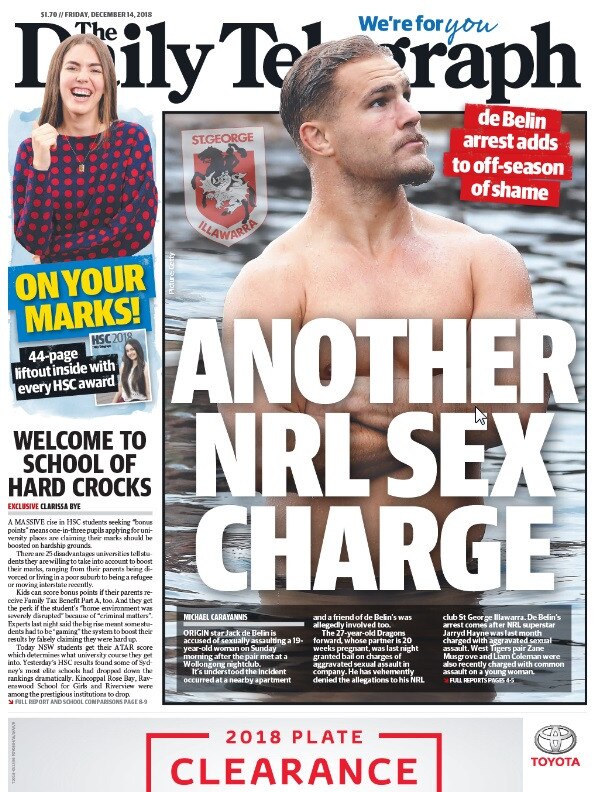

After yet another sexual assault allegation, it is clear the NRL’s processes around player behaviour are not working

Merry Christmas rugby league. How can you love a game which faces five sexual assault allegations over one summer? And while the NRL waits on the courts, the game suffers, writes PAUL KENT.

- Shame: All the NRL’s off-field incidents of 2018

- de Belin surrenders passport over sex assault allegations

- Fittler explains controversial Lodge decision

- Only punishment can fix this epidemic

Rugby league will have a miserable Christmas.

The misery is self-inflicted.

One sexual assault allegation over the summer is terrible. Two is dire.

But five?

There are many good people struggling to explain what appears to be a worsening problem in the NRL. How, they say, can you love a game, and why you should be able to love a game, where it appears the matter is not taken seriously enough by the governing body and where not enough is being done to discourage this apparent life of privilege-gone-wrong by some of its players.

The appearance is wrong but, such is the speed and turnover of the news cycle nowadays, gossip is rarely fact-checked and a whisper in a bar-room is soon Twittered into hard fact. It has travelled half a world before the speaker makes it home.

That it comes at a time when players have more education and more at stake than ever before makes it more confusing for those who do not closely follow the game.

The problem for rugby league is at least half of those people are women, the very people the game is spending millions on to attract.

Women’s rugby league, rejigged junior competitions to make the game mum-friendly, women in league round, players in pink jerseys …

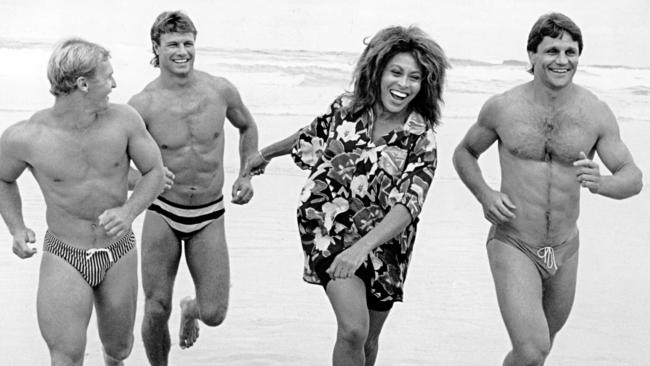

Years back, the NRL did it another way to attract females.

Tina Turner made the game sexy. She made it OK for women to follow the game.

Sex sold.

Not anymore.

The NRL, as a whole, has stuck to a well-worn and convenient template to deal with more recent allegations: acknowledge the complaint, confirm an investigation and state that since it is a police matter there will be no further comment.

It was convenient because it allowed the NRL to be passive and therefore to remain friends with all parties. Let the police do the dirty work of investigation and the NRL could come in later, with the heat out of it.

It gave no mind to the reputational damage to the game.

Shortly after Jarryd Hayne was charged with sexual assault last month, figures emerged showing 58 sexual assault allegations have been made against 28 NRL and AFL players in recent years.

Disturbing numbers, yes. But it is important to note that among them, once the evidence was tested in court, not one player was convicted.

So calls for blanket suspensions once an allegation is made fail to hit the mark, too.

It puts the NRL in a difficult spot.

It is one thing to accuse clubs of skewing evidence to get a required outcome — basically, to clear their player to allow him to continue playing — but to suggest it happens in the courtrooms is a tough sell.

Still, this should not be the standard for sporting codes.

A criminal courtroom which requires a beyond reasonable doubt verdict, and the court of public opinion, which does not, are two different things.

A sporting code, one that attracts tens of millions of dollars in sponsorship money, which relies on public reputation, has to account for that.

The NRL’s current stance fails to acknowledge this point. Civil court, for instance, needs only the probability that something happened.

The NRL must adjust its template to protect the game’s reputation against a growing sentiment — from the very people it is trying to attract — that the game is played by thugs with no respect for women.

After news broke of all five police investigations, a statement shortly followed saying that given they were now a police matter, no further comment would be made.

It is often the final sentence in a press statement, a sidestep from a club exploiting sub judice laws. It has become far too convenient, at the same time giving a widespread impression the game is dismissing the seriousness of the allegation.

That the player then often continues playing or, in this off-season, training with his club adds to that perception.

Nothing stops the game from acting on a matter “under police investigation”. It gets difficult only once charges are laid but, again, within that the NRL can act in its own interest.

A beyond reasonable doubt verdict is not necessary.

Sexual assault cases are notoriously hard to convict.

But while the NRL hides behind a convenient excuse, the game suffers, women in league round is revealed as nothing but tokenism, mums point their kids towards other sports.

The game is not doing enough at the moment. The allegations are becoming more frequent, not less.

Some will argue players need more education.

It seems astounding that young men need to be educated not to engage in behaviour which could result in an allegation they have assaulted a woman.

But the devil is the detail. What constitutes sexual assault? At what point is the line being crossed?

Players get so much education and welfare, they could write the pamphlets themselves. They are educated far more than other young men their age.

What they possess that other young men their age don’t, though, is privilege and often wealth. Mix it with alcohol and opportunity, and that is why coaches and chief executives cannot sleep at night.

Hours before news broke that Jack de Belin, a NSW State of Origin star, was being charged with aggravated sexual assault on Thursday, NRL boss Todd Greenberg told the clubs to get their players in order.

If that is where it remains, the club’s job, rugby league is doomed to repeat its mistake.

Each club’s interest, rightly or wrongly, is not just player welfare but keeping the player happy and in a frame of mind to help win premierships. That is not a politically correct statement, but a fact.

It is the NRL’s job to protect the game’s reputation.

This has to be fixed from the top down. Greenberg has to take charge as the game’s boss, overruling the clubs to make decisions based on available evidence.

Simple rules, stern punishment.

The current strategy does not work.

Every previous NRL chief executive right through to David Gallop, a lawyer, used his discretion to determine the weight of early evidence, against the reputational damage, to determine suitable punishment.

It worked until Brett Stewart got dumped as the face of the game but later cleared of sexual misconduct in court. His shunning by the NRL rose as a great miscarriage of justice.

It made the game cower.

Soon, every case was left to be exhausted in court before the NRL acted.

Reputational damage grew. The NRL argued for its position based on the legal presumption of innocence and the proceedings taking place, somehow overlooking that two entirely different matters were at stake because two different standards were being applied.

Of course, the player is entitled to his day in court, a presumption of innocence and a finding made beyond all reasonable doubt.

For the NRL, that is too late.

Often, by the time a decision is found in court, the reputational damage is done.

Last year the players fought hard during Collective Bargaining Agreement negotiations to be partners in the game. They said they wanted a partnership to help grow the game and share in its profit.

It is time to make the players ante up. If they are genuine, they should understand the NRL’s need to get involved earlier.

Millions of dollars left the game this year — millions that could have been shared with the players — because of poor player behaviour, in part because the game stood mute while player behaviour appeared to go unpunished.

Reputations are earned and, in some cases, they are also simply accepted.

It is time for the NRL to fight for its reputation.

Every Test, ODI & T20I live, ad-break free during play and in 4K. Only on Foxtel. SIGN UP TODAY!