NRL turns to NFL for advice on player welfare in and out of the game

NFL and NRL players are under huge pressure. Now the two football codes are working together to give the young men on the field the skills to cope with life off it, discovers NICK WALSHAW.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Crawley Files: How do Parramatta keep screwing it up?

- Inglis deserves support of the rugby league community

If Everson Griffen wants out of an ambulance, nobody is stopping him.

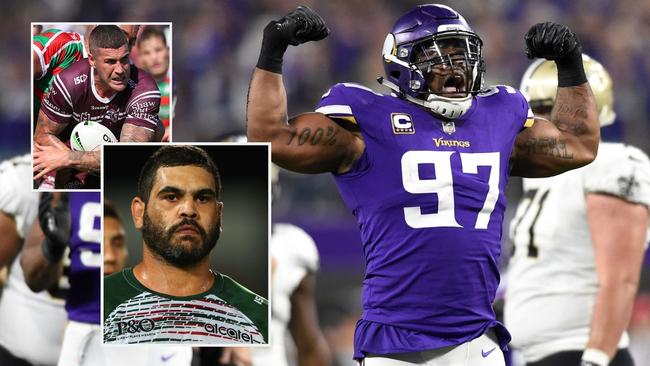

Understanding that as a Minnesota Vikings defensive end, Griffen gets paid $20 million a year to bust through some of the biggest, toughest hombres anywhere on the planet … and then sack their quarterback.

Dubbed “The Freak”, this NFL enforcer weighs 124kg.

And can bench roughly the same, only in repetitions of 30.

While as for covering that famed 40-yard dash … well, this tattooed Adonis gets home in 4.46 seconds.

Or the same time as New York Jets recruit Valentine Holmes.

So you can imagine the chaos last September when, from inside an ambulance which had stopped on some Minnesota back road — for of all things, a crossing deer — Griffen suddenly exploded out through the back doors.

Then, gone. Not only off down the road, he would later tell police, but convinced someone was trying to shoot him.

All up, the episode resulted in this struggling footballer, a fella for whom the ambulance had been called to his home, eventually being coaxed back onto a stretcher, spending time in hospital, being stood down for a month, returning, and across three days on the Gold Coast this week, invoking discussion around revolutionary changes to the NRL landscape.

“Because if we’re making comparisons between sports,” says Dr Nyaka NiiLampti, the head of NFL Wellness, “I’d say rugby league players are closest to the population I work with.”

A leading US sports psychologist with more than 15 years experience, NiiLampti is in Queensland this week to not only head the annual NRL Wellbeing Conference but bring change to a code that is already working hard, and spending big, on mental health.

Apart from having some of the game’s biggest names speak out about depression and suicide in recent years — think Andrew Johns, Greg Inglis, Kieran Foran and Andrew Fifita — the code is also midway through a three-year study into rugby league and youth suicide after 14 players took their own lives within 12 months.

And certainly, league isn’t alone in this battle. A truth proved the moment Griffen rushed those ambulance doors.

Yet speaking exclusively with League Central, NiiLampti suggested that, given the similarities between the two “hyper masculine” sports — and the warriors who play them — there were several NFL innovations which could be introduced to the Australian game.

And top of that list, she says, is every NFL club hiring a full-time psychologist to become director of player wellness.

In recent months Stateside, both the Carolina Panthers and Kansas City Chiefs have employed a psychological clinician to the role NiiLampti calls a “game changer”.

Apart from ensuring mental health is treated like any other injury, the new director of player wellness demystifies the topic, enables easier identification of warning signs, while also allowing athletes who “underestimate the stresses” of football to be helped before an episode — or worse.

Elsewhere, NiiLampti opted out of the concussion debate — “it isn’t my space, that’s Health & Safety” — but spoke at length about the issues facing retired players and the opportunity for rugby league to employ “transition coaches”.

FOCUS ON WELLNESS

In September, Carolina became the first NFL team to adopt a full-time director of wellness, hiring psychological clinician Tish Guerin.

Apart from aiding players struggling with depression, anxiety or loss, Guerin is also charged with creating an environment where regular mental health check-ins are treated no differently to the stretching routine.

NiiLampti says: “It’s unique because Carolina are saying ‘we’re not only putting someone on, we’re bringing them in-house, employing them full-time and really integrating them into every single thing we do as an organisation.

“They’re not only understanding the value of that particular skill set, they’re giving them a seat at the table. And there’s tremendous value in that; in having someone who isn’t only fully integrated, but has complete access to the players. And over time I think we’ll see a greater integration of that role at other organisations.

“Not only because of the support for players, but also it’s also the coaching staff, the front-office staff, everyone. And the healthier those folks are, the healthier your players will be.”

TRANSITION COACHES

Warren Sapp made $82 million in his Hall of Fame career with the Oakland Raiders and Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Yet within five years of retiring, the defensive tackle was bankrupt.

Indeed, just as Sports Illustrated once revealed 78 per cent of NFL players were either bankrupt or under financial stress within two years of retiring, more recent analysis reveals plenty are also struggling with marriage failures, mental health, addiction and more.

In response, the NFL has hired and trained a group of retired players to act as “transition coaches”.

“When a player is transitioning out of the game, when he’s struggling and feeling isolated from everyone, it’s not uncommon that he starts refusing calls from almost everyone,” NiiLampti says.

“But the one call he’ll take, it’s from another former player.

“There’s a real level of trust there, which is why we’ve employed former players as transition coaches, training them in suicide prevention, identifying mental illness signs and so on.”

UNDER PRESSURE

Before the 2017 season, every NFL player was given a bracelet which read The World Needs You Here.

NiiLampti says: “Footballers are extremely visible, but they can also feel isolated.

“By the time they get into the league, they don’t necessarily know who to connect to or why people are connected to them. There’s a scepticism there … do you think I’m making millions? Do you see me as a way onto a VIP list? And that’s before all the other pressures of changing clubs, competing for spots, of coming in every day and fighting for your job.

“Some of the challenges these guys face, they’re things males in their 40s and 50s wouldn’t necessarily know how to navigate.

“Yet we’re expecting young athletes to not only do it, but do it without making a mistake.

“I think there’s an underestimation of the stresses they face. Just as many players underestimate the stress they’re under.

“So these are the discussions we need to be having now. And our focus, it needs to be on building whole athletes, because while they’re all footballers, they’re also all human.”

PSYCHOLOGIST A MUST FOR CLUBS

Every NRL club employs a strength coach. A nutritionist. Even that shadowy black belt who teaches the dark art of wrasslin’. So why not a psychologist?

This is the biggest message from Dr Nyaka NiiLampti, the head of NFL Wellness, who has this week shared ideas with more than 80 members of the rugby league community at the annual Wellbeing Conference on the Gold Coast.

Undoubtedly, the NRL is already working overtime in the space of mental health.

Players like Manly backrower Joel Thompson are outstanding contributors to the State of Mind program.

However, NiiLampti said the next step for rugby league was having all 16 clubs employ a director of player wellness.

Reigning premiers the Roosters are the only NRL franchise with a clinical psychologist on staff.

According to club officials, Insight Elite Performance Psychology has been with the Tricolours since late 2012. A staffer is at Roosters HQ up to three times a week.

However, under the model proposed by NiiLampti, and already used at both the Carolina Panthers and Kansas City Chiefs, each club would not only employ a psychologist full-time but have them based in an office on site and in daily contact with the players.

A host of the NCAA Division 1 colleges have already added a full-time clinician to their athletic department.

Apart from encouraging early intervention, and therefore prevention of issues surrounding mental health, NiiLampti insisted a director of wellness would also improve NRL players “both off field and on it”.