The last living man who won a premiership with the Bears was Herman Peters. He was a centre, and a damn fine one, playing for NSW and topping the try-scoring lists in 1923.

He was there in 1922 when the Bears stomped Glebe 35-3. They were the greatest side to ever pull on the red and black – Peters was one of five Bears who went on that year’s Kangaroo tour, alongside players like Harold Horder and Duncan Thompson, the types of players who are as much myth as they were men.

Peters was the grand old man of the Bears, one of those sorts who does whatever needs to be done. He died in September of 1989, at the age of 90, still waiting for that third premiership.

In the seven years since, Norths had transformed into one of the game’s powerhouse clubs but even then, the only time they were close to the teams of Herman Peters’ day was 1996.

It hadn’t been so long ago that Norths were begging for crusts, taking chances on fellas nobody else wanted or paying too much money for players who weren’t worth it.

That had all changed. Winning makes you handsome, and back-to-back finals campaigns in 1994 and 1995 made the Bears a pretty sight as far as free agent talent went.

Once again, Norths needed some spark, some flash to back up the bash of their forwards, and once again they got exactly what they needed. A fighter can’t stay on the ropes forever, he either gets knocked down or swings back, and the Bears swung back.

Brett Dallas fell into their laps, a benefit of their loyalty to the ARL. A refugee from Super League-bound Canterbury, Dallas was an incumbent State of Origin player for Queensland, one of the few players in the competition who could match Matt Seers for pace and an instant success – he scored three tries in his first game as a Bear, a 42-26 win over Gold Coast.

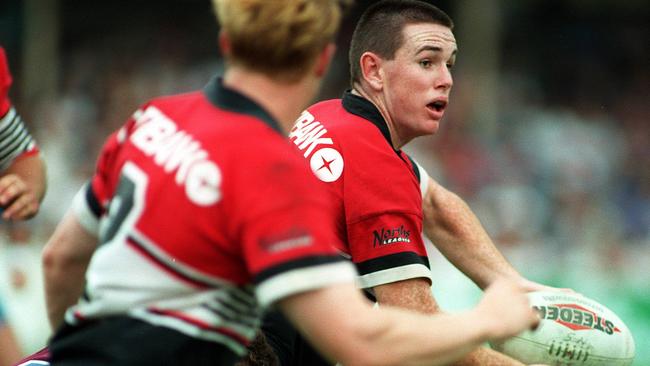

In the centres that day for the Bears was another new face, and a former Gold Coast man himself, Ben Ikin. The youngest player in State of Origin history, Ikin had become a star playing for Paul Vautin’s miracle Maroons in 1995.

He was only 18 and had just eight first grade games under his belt, but Ikin was one of the hottest properties in the league and it was the Bears who landed him. Not Manly or the Roosters, not Saints or Parramatta – Ben Ikin could have gone just about wherever he wanted, and he wanted to be a Bear.

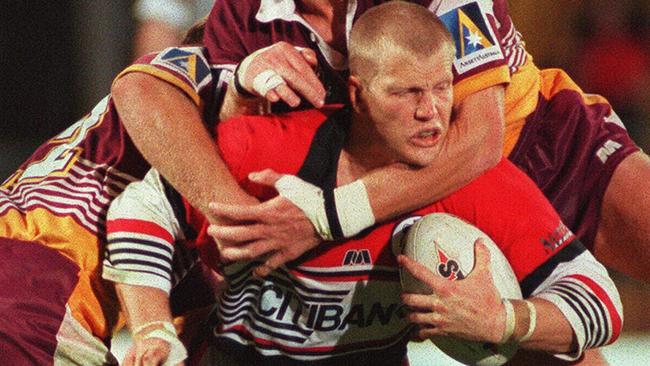

Being a North Sydney Bear meant something, and making it there meant you were somebody, which is part of the reason they captured their third and most important recruit, Michael Buettner.

“The irony is that he was a Parramatta kid, who wanted to play for Parramatta when they were flying,” Soden remembers.

“But Parra were getting beat up, and he had to come to us to play in a successful team. The tables had turned.”

A schoolboy star, Buettner had been good in some battling Parramatta sides since he’d debuted in 1992, but being good wasn’t enough.

“The calibre of player and the success they’d had there, that’s why I signed,” Buettner said.

“I’d played four years of first grade, from 1992 to 1995, and going to the Bears I didn’t think I was going as a first grader. I thought I’d have to earn that right.

“When you look at the likes of Jason Taylor, Billy Moore, David Fairleigh, Gary Larson, Greg Florimo, they’d all had a lot of success.

“So it was a challenge, and it was a way for me to improve my career at least.

“It was what I expected, in the sense that I knew the reputation of the players there. I had a lot of respect for those players, and I felt like I had to prove myself.

“Looking at the training, the way they went about their sessions, the extras they put in. I learned so much as a player from when I was there.

“I knew I had to elevate my levels of commitment, my effort, and my technique.

“I got in good nick, because I had to show these guys who I admired and respected that I was up to it.”

Dallas was raw, unadulterated speed, Ikin was the kind of willowy centre/five-eighth the club believed could one day replace Greg Florimo and Buettner was the total athletic package, quick and strong and willing to take on the line at every chance. Blink and you’d have missed them, and plenty of people were blinking.

They were three players who, as coach Peter Louis told Tim Prentice of The Daily Telegraph in the lead-up to their early season clash with Manly, were “born to run the football”.

The Sea Eagles had only lost three games the previous season, and smashed the Bears twice. They’d joined Canberra and Brisbane as the competition’s goliaths and after their humiliating defeat in the grand final the year before to the Messianic Bulldogs, they weren’t here for anything less than the best. Stomping the Bears was part of the deal.

More than 21,000 people packed into North Sydney Oval on April 7, 1996 to watch the old rivals go at it again, in their 100th meeting no less. Afterwards, Peter Louis said the Bears had come of age, and how they’d dwelt on the two floggings Manly had handed them the year before.

The Sea Eagles led 6-0 early, but a man-of-the-match performance from Moore turned the tide, and in the words of Roy Masters in the Sydney Morning Herald the next day “redemption surged over the field like an unstoppable current.”

The final score was 20-10, and the Bears found the self-belief and absolution which can only come through making the impossible a reality.

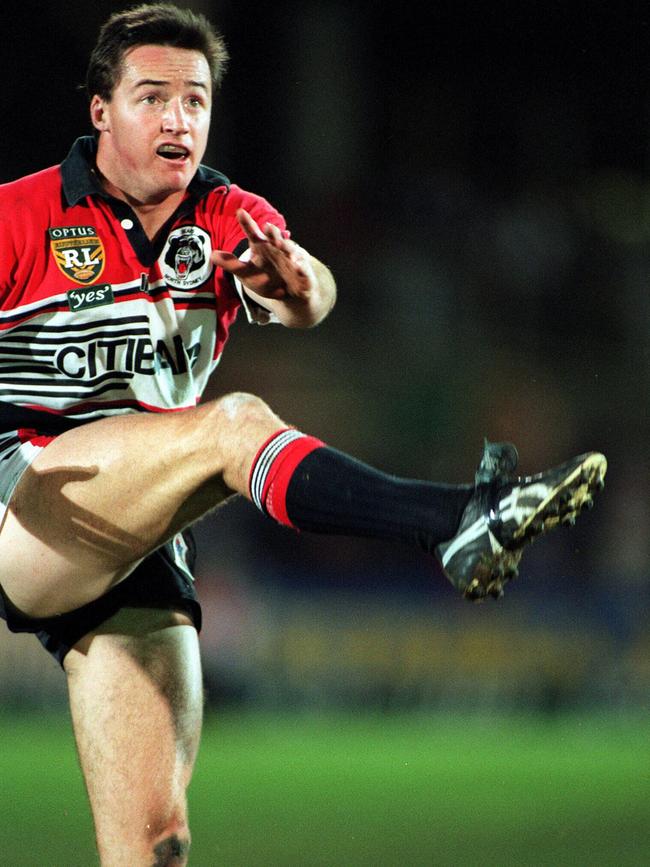

There was one more switch for Louis to make, and it was a big one, because it meant moving Greg Florimo. A veteran of 200-odd games at 28, Florimo was always the spiritual leader of North Sydney. Taylor led them on to the field, but Florimo was a combination of father figure and brother. Asking him to switch positions, from five-eighth to backrow, would involve moving one of the club’s greatest ever players from his preferred spot.

But Louis asked, and Florimo did it without question, because he knew it was best for the team and that’s what leaders do.

“I made sure I had respect from the players by rolling my sleeves up and doing my best, and I tried to always be positive and complimentary of anything anyone did on the field, I found that helped build a rapport,” Florimo said.

“And then I asked them to do a little bit more for us. It was all for the team.

“It was great, I had these runners and all they needed was early ball. I could do the same myself, start hitting holes and running lines off these guys.

“It was really refreshing for me and I could mix up my game. You could see the impact they had on the side straight away. It changed the way we played.

“I was a five-eighth for a long time, but I loved the freedom of picking your lines and waiting for the ball to come to you.”

Buettner moved to five-eighth, Florimo to second-row and Larson to prop, and the Bears became a super power. In having the freedom to move all around the field, Buettner blossomed into one of the most dangerous ball-runners in the competition, and Florimo could still have a serious attacking impact at second-row, while Larson was just as durable, hard-working and inspirational at prop.

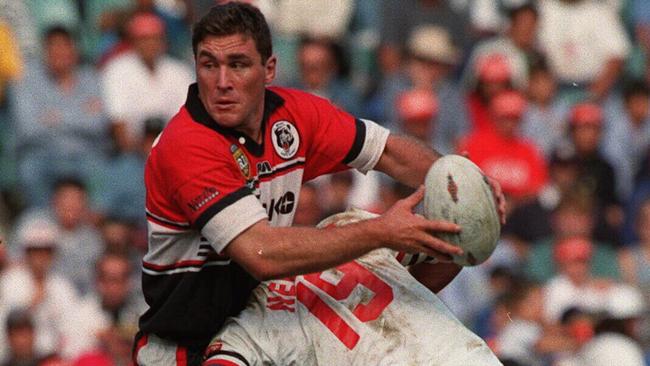

“I loved the opportunity to play next to JT and learn from him,” Buettner said.

“Flo had some success as a back-rower on the Kangaroo Tour a couple of years before, and for Peter Louis it meant he had a viable replacement to move Flo.

“Flo might have lost a bit of that impact as a ball-running five-eighth, but it gave me an opportunity, and it gave us plenty of flexibility in the squad – me, Flo and Ben Ikin could all rotate in those spots.

“It was a really good fit for all of us.

“I’m not one of those ball-playing five-eighths who was always putting people into gaps, my go was running.

“JT could go to the line, he’d have big backrowers hitting gaps and I’d be out the back, and that suited me well and truly – I’d get the ball in space and play off the back of that.

“JT controlled the side, he got us around the park, he did the majority of the kicking, but he helped me develop that part of my game as well.

“We spent a lot of time working on that, just in case I had to. He helped me develop my game further, JT made me look good … but I like to think I helped him look good as well.”

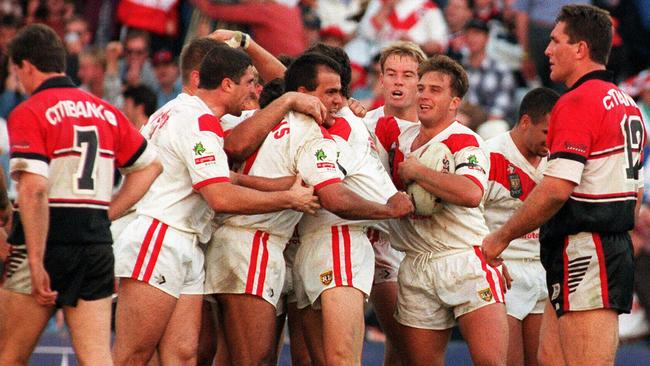

The new-look Bears beat North Queensland 50-6, then destroyed the Dragons 42-0 back at home. It bucketed down, but that didn’t matter. Norths didn’t drop a ball in the first half in a performance Peter Louis called perfect and Ray Chesterton called “joyful turbulence” in The Daily Telegraph.

“If they remake Singing in the Rain, all the Norths players will get leading roles,” Chesterton wrote.

“They were compact, precise, fought for field position on the strength of Taylor’s kicking game in general play.

“St George looked like a team born and raised in the Gobi desert.”

Buettner scored three tries, Taylor kicked nine goals, and the Bears didn’t look like premiership contenders, they looked like premiership winners. Premierships are won in September but are built far earlier, and this looked like a building block, like the point where the players would turn back one day and say that’s where the winning began.

“It was one of those days where if you were a golfer on a par three you’d hit the green every time,” Soden remembers.

“It was indicative of what that side was capable of.”

These Bears still had their tough edge to fall back on, but were just as comfortable running and gunning.

Seers was superb after taking a few steps back in 1995, and Taylor enjoyed his finest year as a Bear, claiming the final Rothmans Medal and producing his best season with the boot, banging over 108 goals from 129 attempts for a strike rate of 83.72 per cent.

Taylor broke his own club record for most points in a season and equalled Harold Horder’s record for most points in a match when he crossed for three tries and kicked seven goals for 26 points against Souths in the final round of the regular season.

Horder set that record in 1922 – the magic year, the year when Norths bowed to nobody – and these Bears gave every indication they were made of the same stuff. Most pundits gave them an edge in tight matches due to Taylor’s kicking, which was something Taylor took very seriously. He tried to find the perfection in the practice, rather than the other way round.

“Practice is important, but the technique of the practice is more important than the practice itself,” Taylor said.

“You can put hours into practice and not be practising in the right fashion. It has to be a technique you’re able to repeat.

“You’ll get better if you just kick ball after ball after ball, and I did a lot of that, but the majority of it was honing a technique you know can stand up under pressure.”

The losses in 1991 and 1994 had taken just enough shine off the Bears for them to ever consider looking too far ahead. That was further reinforced by a change in the club’s victory song. Gone was the rollicking tune of days gone by, replaced by U2’s I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For.

“It’s hard to believe it was 20 years ago, cause it feels like it was 20 minutes ago we were out there training,” Buettner said.

“It was a really good group of guys, and sometimes you get that in your career, when you have that special bond.

“Our manager, he had an army background, and he thought it was something that would inspire us. When I hear it on the radio it takes me back to the Bears.

“It was no choir, I can assure you of that.

“The beauty of playing sport is the impact a win can have, and how good it is to celebrate. Those things stay with you forever and a day.”

To a man, the Bears players remember how close the team was on and off the field, and how hungry they were for success. They craved a premiership like only a starving club can.

“We had a saying – don’t dare put your semi-final coats on, because we’re still digging these trenches,” Soden said.

“We were aware we couldn’t think that far ahead, but we respected what we did have. Let’s love and enjoy what we’ve got. It sounds corny, but that’s just how it was.

“If you were injured you’d still show up to training, just to keep up with everything.”

The Bears only lost one of their last seven games and finished the season third on the ladder, two wins behind Brisbane and Manly.

The Broncos and Sea Eagles were considered destined to meet in the grand final – each had only lost four regular season matches – while the Bears didn’t have the same juice despite their improvement.

They travelled across the border to Lang Park to match it with Brisbane, in what was the final game played at the Cauldron before it was rebirthed as Suncorp Stadium.

Like 1994, the Bears were supposed to lay down and get crushed, but like 1994 they defied the odds and upset the Queenslanders, this time escaping with a 21-16 victory after a magnificent performance from Florimo, who scored one try, set up another and looked like he’d been a backrower all his born days.

It was as fine a win as North Sydney ever had, and dead even with their 1991 finals win over Manly as their best of the decade.

“That was grand final-esque,” Soden said.

“We pulled their pants down in front of their home crowd, and they walk pretty tall up there. They have high expectations of themselves. That was a great win.”

Any match against the Broncos, still the league’s glamour club and now the universal villains following their role in Super League, seemed to have a little extra heat, let alone a finals match.

“There were a couple of clubs you always loved playing against, and the Broncos were one of them, because whenever you played against them you knew you were playing against the best,” Moore said.

“Throughout the 90s they were phenomenal. I was never daunted by playing them, because I loved the challenge.”

It was three tries all, but Taylor’s boot provided the difference. He banged over four goals from four attempts and a field goal. Buettner grabbed a double, putting on a star turn in his first finals match. The Bears were one win away from the grand final, again, with a week off to get ready before a match at a Sydney Football Stadium that would be a red-and-black madhouse. After 53 years in the wilderness it was close enough to touch and impossible to avoid.

“Norths simply played the better finals football than the Broncos,” Paul Kent wrote in The Sun Herald.

“They have to concentrate on their next game (whoever that may be against) when history demands they must be reminded of it incessantly.

“Then they must escape the 8000 wellwishers Jason Taylor sees under the fig tree each week who gave up long ago on a Bears premiership victory, and yet will die hopeful.

“They must do all this, see, because after beating Brisbane 21-16 at Suncorp Stadium they have sounded a warning this competition is no longer about the Broncos and Manly and bugger the rest.”

Sydney City were supposed to be the opponents on the day, but it ended up being St George, who’d scraped into the finals in seventh spot and seemed to have run out fire, before back to back wins over the Raiders and Roosters propelled them into the prelim. That red-and-black madhouse didn’t eventuate, because the red-and-white army swept in and took most of the seats.

The Bears were 6.5 point favourites and everyone’s pick. Five of The Daily Telegraph’s six experts backed them to get home. All the signs seemed to be coming together, it felt like it was meant to happen.

It was just little things – Michael Buettner banged a hole in one at Moore Park golf course during the week, for example. Craig Wilson, nicknamed Prophet of Doom for his gloomy outlook, had his workmates at North Sydney leagues club paste his horoscope for the week all around the place because under the subsection “health” it read “fit enough to slay a dragon”.

Moore, who’d torn his hamstring off the bone against Brisbane, was going to be fit to play after two weeks of intense rehab, which involved three and a half hours a day with the physio and two hours in a hyperbaric chamber.

North Sydney couldn’t escape their history. Their fans and the media brought it up before every big game they played. The Steve Martin days had put paid to the Bears carrying those losses with them, but it was still impossible to avoid.

“There are some traits so deeply ingrained in a club they are almost impossible to eradicate,” Roy Masters wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald that week.

“Like an oily stain or a pervasive smell, it lives within the furniture. Almost as if it’s in the timber grain itself, no amount of polishing, veneering or lacquering will change it.

“The Bears’ problem is they wear red and black and are called North Sydney. They are not taken seriously because they haven’t won a premiership since 1922, or made a grand final since 1943.

“If the woodwork theory holds true, Norths are forever destined to runner-up status.

“Today’s young players are not as tradition-conscious.

“But, like strong undercurrents, the decades of deja vu are still powerful forces.”

But the Bears weren’t looking back, only forward. The dream of a grand final was there to be made, their dreams were in front of them to be taken, and better yet it could be against Manly. Not that they’d ever look past the prelim, no way, not ever, but how couldn’t you dream about it?

Returning to the grand final at last, with not just every Bear that ever drew breath on their side but the entire city, the entire sport, the entire world, cause nobody would get behind the Silvertails. The whole game would turn red and black, and be given a reminder of the value of tradition and tribalism at a time when it needed it so badly.

If there ever was a time in Bears history when something was meant to happen, it was this. The path was all laid out. If North Sydney were ever going to win that third premiership it would be here, now, this way.

It had to happen, and it had to happen like this, with Manly waiting for them at the end, and the Bears could finally give their upstart younger brother a beating like they’d copped themselves so many times. This was the time, this was the place, and these were the men.

It has to happen somewhere.

It has to happen sometime.

What better place than here?

What better time than now?

It felt like destiny, but destiny doesn’t decide these things – the backs of men and the bounces of the ball are the masters of the rugby league universe.

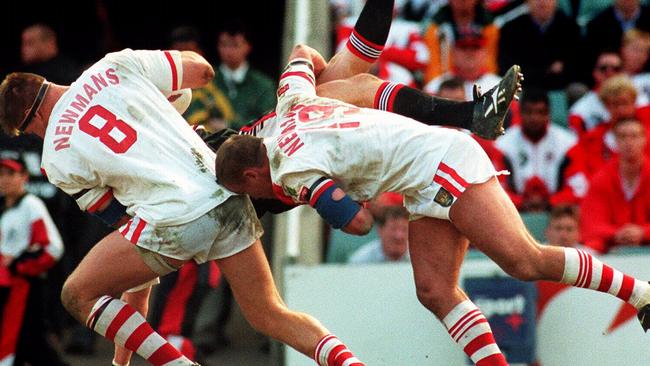

Norths were all over the Dragons early. Fair dinkum killing them without actually, y’know, doing the killing. The Bears made a series of clean breaks early in the match, only for the last pass to fall down at the worst possible time.

“It was the classic thing – in the first few minutes we tore them to pieces, there were holes everywhere, but we didn’t score,” Moore said.

“Then JT, on the left hand side of the field, does a double cut out pass – I was just about to grab it, I was thinking ‘I’ll grab this, and I’ll score’ – but the winger, Mark Bell, he’s blindsided me, grabbed it mid-air and nearly went the length.

“Two minutes later they score.

“I remember behind the try line, I looked at us, the senior players, and I realised we didn’t have a Plan B.”

It was here that the glittering win from earlier in the season came back to bite the Bears – or at least, that’s Taylor’s view on it.

“I don’t have great memories of that result, cause it drove the Dragons to a point where they were so on edge when we played them in the semi-final, and they had vivid memories of what we’d done to them the time before,” Taylor said.

“You see it so many times – a team bounces back from a loss like that because of the pain that they feel, and the team that dished it out, there’s maybe a one per cent thought in the back of their mind that ‘we’re too good for these guys’ and that can be all it takes.

“You see it week after week, year after year. For me, that big win was probably the worst thing we could have done.

“I’d have been happy to lose that game and go into the finals with the desperation the Dragons had, because they had desperation from the very first minute.”

After Aaron Raper opened the scoring, Noel Goldthorpe put the Dragons up 7-0 with a field goal. It was a move straight out of Taylor’s playbook, and Goldthorpe was well-versed in Taylor’s abilities given he was once his understudy at Wests.

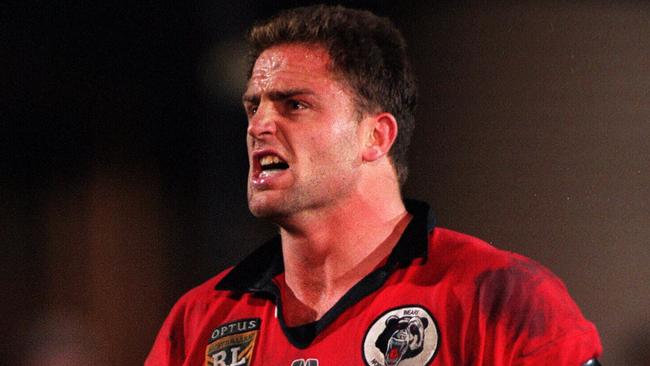

Seers got the Bears back in it when he crossed just before half-time, but in the second half the Dragons continued their hustling, bustling ways. Saints gave Taylor no room to breathe with their intense line speed, and Norths couldn’t get anything else going.

Ten minutes after the break, Dragons five-eighth Anthony Mundine took an offload from Wayne Bartrim and flew up the centre of the field, throwing his head back like Reg Gasnier and scoring next to the posts and driving a dagger through North Sydney’s heart.

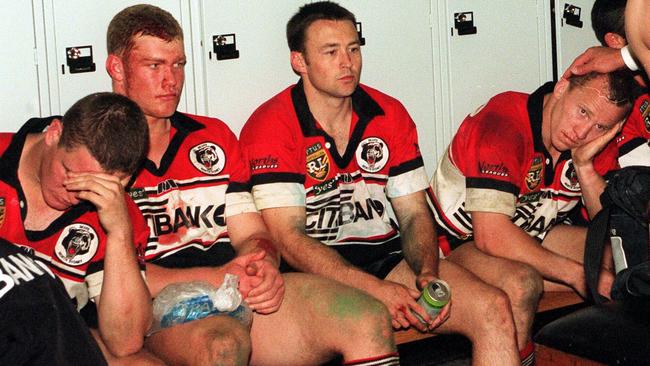

Soden grabbed one back to give the Bears some false hope but two late tries blew the score out to 29-12 and the Bears’ grand final dreams were dead and gone, again. It had been a wonderful season, a brilliant rise, but when it was all over they were in the same place as the 74 years prior.

“You don’t win premierships in the middle of the year, and if you look at the footage of the two games we didn’t improve,” Moore said.

“The 96 Saints side wasn’t up there with the 92-93 Saints side – it’s one of the biggest regrets of my playing career, I know I let myself, the fans and the team down.

“I look back and I think maybe I was so focused on getting back on the field I didn’t get to have enough time to be around the boys, maybe think up that Plan B.

“We didn’t follow the Pat Jarvis mantra, we thought we deserved to win and we didn’t go out there and take it.”

It was one of the great finals upsets, as Saints made the grand final from seventh. It came out the night before the match, as the Bears grappled with the weight of expectation, history and destiny, and the hopes of a lifetime that rested on their shoulders, the Dragons had met at a club official’s house and shot some hoops.

Their secret was their lack of expectation, which meant a lack of pressure. They didn’t have a 70-year premiership drought hanging over their heads. Even if Saints lost they still had 11 in a row and all the rest. The Bears had tried so hard to leave their past behind them and forge some new hope, but as they say it’s the hope that kills you.

“It’s hard to pinpoint why a team exactly wins or loses, but we certainly didn’t go into the game underprepared physically,” Buettner said.

“I’m not here to make excuses, the Dragons were better on the day and they were too good for us.”

The next day Manly duly booked their place in the final game of the season with an easy victory over Cronulla. The Sea Eagles won the grand final 20-8 and didn’t look troubled for a second.

The 1996 preliminary final isn’t something that’s easy to get over – Billy Moore still describes it as the greatest regret of his professional life – but a record trouncing of Manly always helps.

Super League coming to fruition meant 1997 was a strange time for everybody in rugby league given there was two competitions, but old-fashioned local derbies still meant something, as the crowd who charged on to North Sydney Oval following the Bears’ 41-8 victory midway through 1997 can attest.

Florimo earned a rare perfect 10 in Rugby League Week’s player ratings, producing one of the best games of his long career in North Sydney’s biggest ever win over the Sea Eagles.

“I dropped a ball that day, so I don’t know how I got a 10,” Florimo laughs.

“One person ran on, so they all did it. They hadn’t done it for a long time so it was good to feel the back slaps and the yeehas, it was great.”

Buettner was injured and didn’t play, but he vividly recalls Florimo’s day out.

“I remember watching from the sidelines and seeing the great one tearing Manly apart, there’s very few times when you get the chance to sit back and see magic happen on a footy field,” Buettner said.

“Everything went right for him that day.”

At one point, Florimo, facing his own goal line, 10 metres inside his own half, got thrown the ball in broken play and bombed it back over his head. Craig Hancock dropped it, and David Fairleigh was on the spot to score. It was that kind of match.

“The Bears not only had a picnic, after they finished they smeared the Sea Eagles with honey and left them for the ants to devour,” Greg Prichard wrote in The Australian.

For most of the 90s, the match doubled as a top of the table clash, but it didn’t matter where the two teams were on the ladder, there was always plenty of heat.

“With Manly, it didn’t matter if it was last versus second last. The game would always be significant, and we’d always bash each other. It was always a big game,” Moore said.

“I made my run on debut against Manly, at North Sydney Oval, and I look back at it as one of the great experiences of my life.

“We were coming last, they weren’t going so well either, but it felt like a full house and we won, and that’s when I realised it didn’t matter where Norths and Manly were on the table, when they play each other it matters.”

Sometimes the Bears fans didn’t have the fire of their rivals – more than once they were dubbed “the champagne and pate” crowd – but taking on Manly always brought out the best in the supporters, as it did the players.

“The fans they just loved that game, and they loved to win it like nothing else,” Taylor said.

“It made their lives, for 12 months anyway. You say Manly and I think Cliff Lyons, he’d been around for 20 years but he was still doing it.

“One of my favourite memories of Cliff Lyons is when we were out at Brookvale one day, and he was sitting on the bench. Flo and I were watching reserve grade, and Flo pointed to Cliffy, who was having a cigarette.

“They came out and beat us by 30, he set up every try, and he was smoking before the game.

“You knew every one of our players was fitter than him, to a man, but he could do some magic stuff on the field, it was a pleasure to play against him.”

Rugby league clubs are built on tribalism, part of being in a tribe is taking on the others and there’s nothing like sticking it to the neighbours.

Norths found identity in their clashes with Manly. They wore red and black, they were called the Bears, and they hated the Sea Eagles, and everything else was everything else.

“It was great how the fans got behind it,” Florimo said.

“There was so much passion in the lead up, and there was always respect. It’s part of what the club is built on, is that rivalry with your neighbour, and using that to try and find an edge.

“We still do that with our juniors, we talk about the history of the club and what it’s like to play Manly, and the other clubs.

“A big part of the Bears season is the couple of games against Manly, and we always tried to live up to the hype.”

Those 500 fans ran on to the sacred pitch at Bear Park following the record win in 1997, and it was as much in defiance as celebration.

The Super League war was still raging, but as eyes turned to the future, the long-term prospects of the Bears came under the spotlight. The war wouldn’t go on forever, and across the two competitions there were 22 teams – way too many in anyone’s language, and the crowded Sydney market was in the firing line.

Norths had their diehards, and they had roots that went deep down in their traditional home, but the ground wasn’t as fertile as it once was.

A merger with Manly, the doomsday scenario, had been mooted, and some of the supporters who ran on the field carried anti-merger banners. The more attractive option was a move to the Central Coast – a traditional rugby league hotbed with a scope for growth North Sydney just couldn’t match.

By July, it was all but assured, and the football club members voted for the move in December, only a few days after the ARL and Super League called their truce. Leaving North Sydney would be heartbreaking, but vital.

The other foundation clubs on the brink of disaster would hold on to their old places forever, even under pain of death. Norths made the tough choice, the right choice, and they made it early. Everything was supposed to work out OK.

Before all that though, there was still a season to be played. The 1997 Bears might not have had the ceiling of the 1996 version, but they were still experienced, tough and dangerous, and among the premiership contenders all season.

Apart from their record win over Manly, they downed the Roosters by a point in a classic encounter in May, and beat the ascending Knights twice, including a 26-6 brutalising at Marathon Stadium in arctic conditions which resulted in more than one player being treated for frostbite.

The Bears finished with another top four berth, and the ARL’s bizarre seven-team finals series forced them into a pointless minor qualifying final against the Roosters. The winners would not receive a week off and the losers wouldn’t be eliminated – Sydney City won 33-21 in extra-time following a match that was objectively entertaining but lacked the high stakes drama of a true knockout clash.

From there, the Bears did the job on Parramatta 24-14 to set up another prelim, this time against Newcastle. With three preliminary final defeats under their belt, the Bears had already built an unfortunate reputation – they might not have carried the scars of the battling Norths sides of the past, but they’d created their own.

“Imagine the torment of not being able to talk about, or even think about, something that has been a lifelong obsession when the goal is so close,” Jeff Dunne wrote in The Australian the week of the prelim.

“It would come as no surprise then, especially to the tormented souls known as North Sydney fans, that the words ‘grand final’ are strictly taboo in Bears camp despite being just one game away from it.”

Florimo believed that 1997 side was just as capable of winning a premiership as the year before. Their experience from 1996, as heartbreaking as it was, only made them stronger.

“My game was a lot more calm and measured. We had the team that missed out the year before, so we’d learned a few lessons,” Florimo said.

“We had the right preparation, we were ready for it, and God willing we’d get there.

“That was the one we should have had, that was when I really felt a little handle on the grand final that day.”

This time, the Knights were the inexperienced little rabbits and the Bears were the seasoned veterans who’d seen it all. Manly were in the other prelim, against the Roosters, and the dream of the Northside derby playing out on grand final day was alive again.

This was far from the golden, sun-drenched days of earlier in the decade. Even with Newcastle’s famed travelling contingent, the ravages of the war kept the crowd to 22,000 as the Novocastrians and the Bears slugged it out on an SFS mud heap.

It seemed to play to North Sydney’s strengths, but Seers was trapped in a funk and struggled to clean up the kicking game of the Johns brothers. The Knights scored twice off fumbled kicks in the in-goal, and the Bears couldn’t get their attack together for much of the match.

Case in point was Seers nearly getting over in the 60th minute. From their own quarter line, Buettner surged forward and had Seers in support off his hip.

“Mickey Buettner passed me the ball and Robbie O came over, he knocked me down, but it was so wet I slid along, got back up and went again,” Seers remembers.

“Albie was coming across, I probably should have stopped because he was coming across that fast, or slid because it was so wet.

“If I dived from five metres out I probably would have scored. But that’s the way it goes. He was a quick player, Darren Albert, a great player, and he got me with a good one.”

Albert dragged Seers down as the Bears fullback reached the corner post in a classic cover tackle. If Seers had run another metre, he would have made it, but he didn’t. Seers was the second-fastest man in the sport, and in a typical twist of Bears luck, Newcastle had the fastest.

An inspirational display from Fairleigh, who battled through an ankle injury, helped keep them afloat. With 15 minutes remaining, they finally broke the Knights open – Nigel Roy went in off a questionable Buettner pass, and nine minutes later Buettner did it himself, combining with Florimo to score and level things up with five to go.

It was a superb display from Buettner, who looked North Sydney’s most likely all day. After learning the finals ropes the year before, he was desperate to prove himself on the biggest stage, against the best players. That, after all, was why he came to Norths in the first place.

“I always loved taking on the better players, guys like Brad Fittler and Laurie Daley. You had to test yourself, and there was plenty of times I was embarrassed and they got the better of me,” Buettner said.

“But I like to think there were times when I held my own, maybe even got the better of them a bit. I was fortunate to play in that great era when there were so many legendary players and names.

“There’s some games that are still clear in my mind and the Newcastle game is one of them.”

The Knights had been on top all day, but the Bears had hung on and hung on and hung on some more. The roles had been reversed, now they could snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Taylor was the best goal kicker in the game, no question about it, and he’d kicked them to victory a thousand times before. Taylor’s entire game was consistency, doing the same thing again and again and again, until it was automatic.

It was a tough kick – maybe 15 metres in from the sideline, on the bad side for a right-footed kicker, but he’d knocked them over from there plenty of times. That season Taylor was at his apex as a point-scorer, breaking his own club record for points in a year yet again, putting up 242, which would remain the second best total of his career.

Everyone thought he’d kick it. The commentators, to a man, backed him in. How could they not? He was Jason Taylor, kicker of goals, scorer of points, lord of conversions. There’s a reason players lifted all those weights, and there’s a reason Taylor practised these sort of kicks.

Taylor hung it out to the right and the ball refused to hook back. No goal.

Matthew Johns put the Knights in front with two minutes left via a field goal from 30m out that rose from the muck. Brother Andrew was usually the field goal man – Matty had torn his thigh taking a shot the year before and wasn’t even supposed to be kicking them, let alone sending the Knights to a grand final with one. But he did, because these are the kinds of things that happen in fairytales, and those tales need someone to be vanquished.

The desperate Bears threw the ball around in the final seconds and put in a last-gasp kick which was snatched up by Paul Harragon, who found Leo Dynover in support before Owen Craigie backed up. The young centre pranced 20 metres to score, dancing on North Sydney’s grave and handing the Knights a 17-12 win and a grand final berth.

“This just seems to happen to us all the time,” Louis said after the match.

“It’s demoralising to get so close and miss out, but I guess it’s just a thing the Bears have to live with.

“I’m proud of the players; they did everything they could, but luck was against us.

“I’ve got no problem with Newcastle, we can beat Newcastle any day of the week, it’s the Johns boys I’ve got a problem with.”

Veteran winger David Hall wept openly in the sheds, his future uncertain after seven years in the red and black. Les Kiss, who was there back in 1991 when Hall was bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, consoled him.

“So what beat North Sydney this time?” Paul Kent asked in The Daily Telegraph.

“They should bring in NASA scientists to work out exactly what goes wrong. If it is a curse, they should bring in an Aboriginal elder to lift it.

“It is no longer a job for a coach, it’s too much for one man.

“A lesser man than Peter Louis would have hung himself from the Moreton Bay fig by now.

“It is not that the Bears lose, they see the problem and fix it. It is they lose and find a different way to do it each time.”

As with Halligan six years before, no Bears man blames Taylor for missing the kick – they closed ranks around him immediately, with Louis making a point of noting the unfair criticism Taylor copped already.

“I’m glad they were taking the kicks and not me, and I wish they made it but they didn’t,” Moore said.

“It would have been so tough on them. It was hard for us and the fans, but it would have been even tougher on them.”

Buettner points out the Albert tackle was almost as big a play as his grand final-winning try against Manly the week after.

“Scoring that try, there was only five to go, we’d worked really hard to get back into it, and we had this momentum in the last 25 minutes. It felt like they were on the brink,” Buettner said.

“JT’s record is almost second to none when it comes to kicking, you’d expect him to kick anything 99 times out of 100, but unfortunately he missed one.

“But there was still time, and it was the Matty Johns field goal that got us, it wasn’t a case of us giving up. We felt like we’d never beat that bloody curse.

“”A lot of people forget Darren Albert’s tackle – I know he scored that try in the grand final, but he didn’t just win them the grand final, he got them there.

“It does take luck, and Newcastle had the luck on that day and that’s fine, and they rode it all the way through. Their story is a fantastic one, it really put Newcastle on the map.

“I remember watching the grand final the next week, watching Newcastle score that try and thinking it could have been us.

“The Bears didn’t get their fairytale, and the Knights did, that’s why a premiership is so special.

“I doubt there’d be one player who wouldn’t say luck matters, be it injuries or whatever comes along during the year.”

Seers had now been through three prelim losses in his four years in first grade, and had a hard-earned lesson about what it took to go all the way.

“You realise how hard it is to win a comp, you need so many things to align at just the right time,” Seers said.

“It just didn’t happen for us. Sometimes things just don’t work out the way you want.”

Florimo, who had heard the clock ticking on his career at the time, can still find meaning in the suffering.

“It’s a shit world sometimes, but the footy gods either smile or frown.

“Who wants to be a goal kicker? Not me.

“But if that’s the way it is, that’s the way it is, and we might have other little victories in life, but we didn’t have them on that day.”

Footy players don’t like believing in curses, much less talking about them. The idea of a curse implies a result is beyond their control, that the outcome of a match was predetermined before they ever set foot on the field.

We all like to believe we are the masters of our own fate – curses, hexes, hoodoos and the like place us on a straight path with no deviation or choice as to which direction we head. It’s the difference between an assembly line and choosing your own adventure.

Despite the misfortunes that befell the Bears, Moore is clear-eyed in his view on all four prelim defeats. He, Larson, Fairleigh, Florimo and David Hall are the only players who appeared in each match.

“The question I ask myself is why we were good but not great, and you can say how close we came but you can’t argue with the fact that we never went to a grand final,” Moore said.

“I always said if we went to a grand final we would have won it, but why didn’t we make it? The reason is this – we stopped improving. If they gave out trophies in July or August, we were the best team in the comp.

“But when we got into September, we stopped improving as a group. The hardest thing to defend against is something you’ve never seen. We did the same plays the same way, and we were good at it, but that was our problem.

“We never, ever thought of a Plan B. That, in the end, was the difference between Norths being one of the teams of the decades, and that’s what shits me, being known as the “almost”, the unlucky ones.

“I expected to win. I wish it didn’t have to be that way, but because we never made the GF there’s not much ammo to fire back.”

That 1997 prelim was the last one the Bears ever made. They had plenty of the same personnel around in 1998, and were still a dangerous side, but for the first time in a long time the ravages of age were starting to show.

With Adam Muir and Glenn Morrison arriving, the vaunted forward pack was in transition. They could still hold their own of course, but they were no longer the towering physical force of earlier years.

Norths finished fifth, and ended the season with six straight wins, but they only beat one top four side all year. There was a horror show against Brisbane early in the year when the vengeful Broncos won 60-6, handing the Bears the greatest defeat in their history.

The Bears met Parra in the first week of the finals and, to put it delicately, had the shit kicked out of them. They were already reeling, as Fairleigh battled a badly broken nose, Muir had a crook knee, Ben Ikin had the flu, Seers had a bad hip, Brett Dallas had a dodgy foot and Soden battled knee and shoulder problems.

It was a wild, violent match. Taylor had his nose broken via a high shot from Dennis Moran and the Bears tried to seek vengeance for their injured captain.

“I wanted to bash him (Moran), and that game turned feral after that. I said to the boys there were no more rules,” Moore said.

“JT was gone and we didn’t even get a penalty, and he was the captain so I tried to say a few things. The referee had the shits with us because we tried to make the game lawless.

“They were too far in front, we’d lost our playmaker, so we had to go feral.

“(When that happens) it feels lawless, and the strongest survive from there. It’s not a pretty thing, and it doesn’t happen often, but sometimes it takes hold, and then it’s anything goes.

“We had some blokes in the team who were pretty keen on that, Danny Williams, Josh Stuart, Brenton Pomery.”

As it turned out, the Eels won the battle and the war. Their 25-12 victory put Norths into a sudden-death clash with Canterbury, who were going on their own run through the finals from ninth spot.

The Bulldogs’ two extra-time victories from those finals live large in the memory but their 23-2 belting of Norths does not. Norths were off the boil all night, unable to recover from the Parramatta mugging, and even the magic of Bear Park couldn’t get them home.

It was a drab and forgettable end to Greg Florimo’s playing career with the club. It was shocking at the time and even stranger now, but Florimo left the club at the end of that season for England. The only comparison to Florimo leaving the Bears would be the Pope leaving Catholicism.

“It was a matter of looking around me and seeing the plethora of back-rowers we had, including new kids like Adam Muir and Glenn Morrison,” Florimo said.

“I thought I might have to look around, and there was an offer on the table, which wasn’t what I thought it should be.

“I couldn’t play for another club in Sydney, it wouldn’t have felt right to play against the Bears.”

So Florimo was bound for Wigan, and he departed as the most capped Bear in the club’s history, a red and black legend, always.

“I can’t believe that happened,” Soden said.

“I love Flo, he was a hero to me. I was watching a game from 99 the other day and I’d forgotten he wasn’t there. It felt empty.

“The side wasn’t right without Flo. He is North Sydney. He’s it, and it was hollow to not have him there.”

Ben Ikin tried to follow Florimo out the door and head to Brisbane and was locked in a bitter contract dispute with the club for much of the summer. There were serious doubts over Seers’ future after he went to rehab for substance abuse. Moore’s rep career ended, as did Fairleigh’s. The stars were getting older, the cycle of rugby league was beginning again, and new stars would have to be found for the new millennium.

The Bears would be a part of that millennium, no doubt about it. There’d been rumours of a merger with Gold Coast, but they quickly fizzled out.

The Central Coast Bears, that’s what they’d be, wearing the red and black proudly, keeping the tradition alive, maybe getting back to North Sydney Oval once a year or so. That final against Canterbury was supposed to be the last game played at the old girl, before they moved north, to their new home, the land of milk and honey and juniors and money that would keep them alive forever.

By moving out of Sydney, the Bears would be classified as a regional club, and thus were sure to survive, that’s how it was supposed to be.

There was genuine optimism at the end of 1998 for the Bears. They had a future mapped out, a glorious new home under construction just up the coast.

But the glittering palace on the horizon was a mirage. The Bears never made it to Gosford. Extinction was staring them in the face, they just didn’t know it.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout