The North Sydney Bears too many people remember are the loveable losers, and that was true for a long time until it wasn’t anymore.

The Bears weren’t supposed to win, but there was a time when they did, a lot, and more than once they nearly ended the longest premiership drought Australian rugby league knows.

It didn’t last, because nothing does for poor old Norths. Death isn’t supposed to sneak up on you. There’s not supposed to be an express line from the penthouse to the graveyard.

The Bears nearly had it all, then they had nothing, and they did a whole lot of living before they died. This is the story of how it all happened.

You heard the one about the new Bears coach?

He told all the players to get in their regular positions, so they lined up behind the goalposts.

Or how about the fella who left two tickets to the Bears game on his windshield yesterday?

When he came back there were five.

Want to hear a sad story in three words? Lifelong Bears fan.

That was North Sydney’s lot in life for a long time, and I do mean a long time.

Parramatta fans gripe about their premiership drought, Cronulla went 49 years without winning a title, but the Bears have them all beat.

You want a long time between drinks? Try seven decades and counting. Try making your last grand final during World War II. Other teams might adopt a lengthy absence from September, the Bears were moulded by it.

After the Bears won their two titles in 1921 and 1922, the latter being one of the great teams of all time, a red-and-black dynasty beckoned, but it never came to pass.

They built the Harbour Bridge in the 1930s and the district changed forever. There was one more grand final appearance, in 1943 against the Jets, but Norths lost. Then Manly came along in the 1940s and made a hobby of taking the Bears’ best and brightest.

Even Ken Irvine, North Sydney’s greatest ever player, running in an impossible 171 tries from 176 matches, left for the Sea Eagles in the end, winning the two premierships his Bears could never give him.

Nobody hated Norths. In fact, most people liked them. They were friendly, unthreatening, and North Sydney Oval was pretty as a picture.

That was the lot for the Bears. They never hit the soul-crushing lows that Newtown and Wests hit at times, but they never got the other side of it either.

Things just never happened the way they were supposed to – like when they signed Barry Glasgow from Wests. Glasgow kicked 29 field goals in 1969, a premiership record, so Norths made moves to land him for 1970. Field goals then got reduced from two points to one, and Glasgow kicked just one in four years for the Bears.

By the mid-1980s, the Bears’ greatest days were black-and-white photos on the wall and dusty pages in forgotten footy books. It was hard to remember what a successful Bears team even looked like. From 1955 to 1990 they made the finals three times. Not once did they win a finals match.

Norths were proud, but Norths lost. That’s just the way it went, but sometimes, eventually, it goes the other way too.

If North Sydney were to ever build on their two premierships, it’d have to come from within.

The Bears had tried to buy the stars they needed plenty of times, but it never worked out the way they wanted.

Plenty of clubs say they want to back their juniors and plenty of those same clubs prefer to flash some fat stacks of cash to give the juniors a few stars to look up to. That wasn’t really an option for North Sydney – big money had only brought them big trouble in the past.

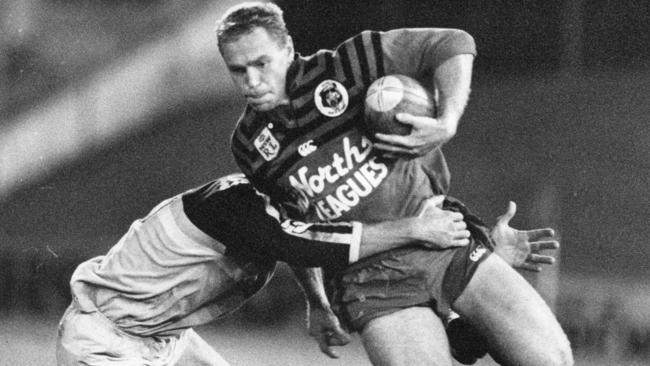

They came from all around. Greg Florimo was the first of them, a fair dinkum local product, just about straight off the hill and into the top grade. Florimo was inspired by the 1982 side, who finished the regular season in third spot before a straight sets exit from the finals.

“I thought they were destined for success and I wanted to be a part of it, and I wanted to help bring it to the club,” Florimo said.

“That was where the seed was planted.

“Watching from the crowds and seeing these big men, like Don McKinnon and Bill Hamilton, and the awe in which they were held by the crowd, that was what I wanted to be, and that was what I wanted to do.”

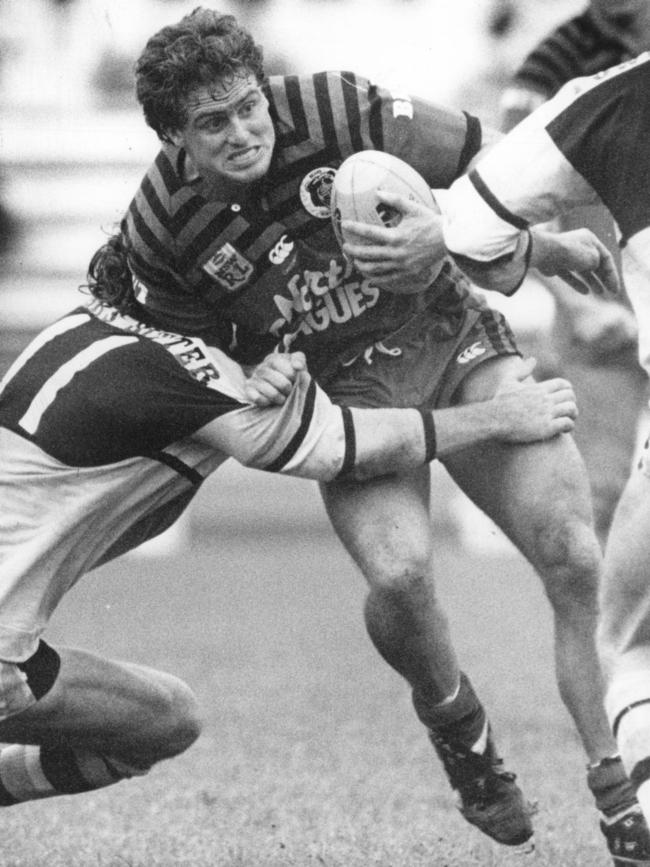

A few years later the others came along. Mark Soden was a junior star, captain of the Australian Schoolboys, the pride of Dubbo, and not the sort of player Norths usually landed.

“Dubbo is a big St George town, so everyone thought I was going to sign there. Roy Masters flew up to see me, which was unbelievable for a kid, to have him sitting in your lounge room,” Soden said.

“I was set to sign, but we had talked to Norths and being nice country people we rang Norths to say I was going to sign with Saints. They said ‘don’t sign anything today’. Next day, they doubled everything.”

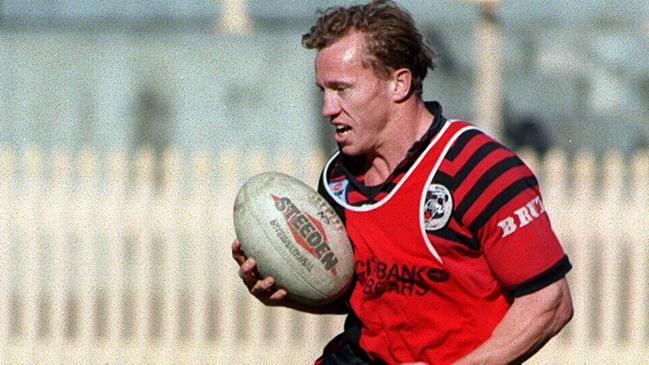

Billy Moore was a skinny backrower who never made a junior rep side growing up. Nobody ever really did in Wallangarra, but Moore was a late bloomer, and earned some interest after starring in an under-17s interstate clash.

“I had four offers – Brisbane, Penrith, Parramatta and the Bears. My mother said ‘you’re going to Norths’, which was strange given we came from Queensland,” Moore said.

“I asked her a few years later why she sent me to Norths and she said she was being pragmatic – she wasn’t sure how good I was. I didn’t play any rep football until I was 17.

“Brisbane had 20 Billy Moores, Penrith had 15 Billy Moores, Parramatta had 10 Billy Moores, Norths had one.

“I didn’t think much of them. I’m from Wallangarra, it was a backwater, and I had no comprehension.

“I was a Parramatta fan, but I knocked that back. You never argued with your mother. Nobody in my area had even been given a contract, ever.

“I’d been to Sydney once before, so I had no idea what North Sydney was like compared to Parramatta and Penrith.

“I rang my parents after I got there, they asked me what North Sydney was like and I said ‘mum I can’t believe it, everyone’s rich’.”

Gary Larson was a wiry centre from Gladstone who became a rugged back-rower after a knee injury robbed him of some pace. David Fairleigh came down from Ourimbah on the Central Coast. David Hall was a shifty winger from Baulkham Hills. Tony Rea blew in from Queensland and Jason Martin from Newcastle.

There was a transformation happening at the Bears, the new generation were filtering in and forming the foundations for a belated era of prosperity.

It’s not like they all stormed in at once, and it didn’t happen overnight.

“It took a while, and it didn’t happen quickly, but you could sense the change was happening,” Soden remembers.

“Not a clean-out, more of a changing of the guard. Guys like Clayton Friend, Mark Graham, Olsen Filipaina, they were all at the end, and Norths were attracting lots of schoolboys players.”

Florimo was a consistent first grader almost from the day he debuted in 1986 – he was one of those guys who starts so early and has such presence that they’re a veteran by the time they hit their mid-20s.

Moore was an early starter as well – he was still 17 when he ran on for the first time in 1989.

“I played first grade in Round 2 of 1989, I was 17 years and 10 months, and I weighed 80 kilos,” Moore remembers.

“With about five minutes to go, we were down by 30, and I didn’t think I’d get on. But the message came down, and they sent me out.

“I ran past the hooker and captain, Tony Rea, and I said ‘Tony, I’ll take it up off the tap’ and he said ‘really? Are you sure?’ I said ‘give me the ball’ so he did, and I ran straight at Mark Geyer and Peter Kelly and I got knocked out cold.

“I was the 10th youngest first grader ever at the time. That record has changed since then, but what has never changed is I hold the record for the shortest ever debut. I woke up in the change rooms.”

The final days of the 80s gave no clue of what was to come. Under former Manly premiership winner and one-time Australian Test coach Frank Stanton the Bears had finished ninth in 1988 and 1989, pretty standard fare in North Sydney.

But what made the new breed different was a freedom from that past, a rejection of the box the rest of rugby league put the Bears in.

“We expected success, we’d all won in the juniors and reserve grade. What do you mean the Bears had this monkey on their back? What do you mean the Bears are this bunch of losers?” Moore said.

“We didn’t believe in it, we didn’t know it, so it didn’t reverberate.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Soden.

“You can get used to losing. And I don’t want to put a blight on anyone who came before us, but Norths weren’t really expected to win, and I’ve never not expected to win,” he said.

“And if I don’t, I take it personally. What did I do wrong? How can I get better? How can I be a better captain? How can I motivate someone else around me?

“Winning was the end goal, not Mark Soden’s ego, cause I loved winning.”

A host of those young Bears, including Soden, Fairleigh and Moore, played in the club’s 1989 reserve grade premiership victory, under the coaching of Steve Martin. When Stanton moved on, Martin was the clear choice to replace him.

Martin was a bolt of lightning for the Bears – at 33 he was one of the youngest coaches in the NSWRL, younger than some of the players he’d coach against, but he was used to winning, having captured a premiership as a player with Manly in his first season in Sydney back in 1978, and when it came to footy know-how he bowed to no man.

That was an important ethos for the Bears, who were so often trampled, bullied and outmuscled by their richer, more successful rivals.

“All this talk about the Bears being losers, I didn’t give a shit about it,” Moore said.

“I hated it, I despised the fact that we even mentioned it, because that was the legacy of the past, that wasn’t something we’d carry into the future. That’s what Steve Martin told us.

“Really thorough, very driven, he knew exactly what he wanted. You were a square peg in a round hole if you had to be, because you were going to fit into his system.

“You had to conform or there was going to be an issue, but he took Norths from also rans to the next level.”

Jack Gibson had pioneered pillaging American football for coaching techniques – a common practice in the modern day, but back then it still had the essence of the mystical about it.

Martin was well-versed in the methods of Vince Lombardi, a Green Bay Packers legend and coaching demigod. Lombardi prized discipline, punctuality and endless competition through perfection at practice.

“A couple of Vince Lombardi’s things were about punctuality, respect for where you were and things like that, but also depth through every position,” Soden said.

“If you have a quarterback, you need two good quarterbacks behind him, pushing him. That’s what he was doing at North Sydney.

“He wasn’t just building first grade, he was building depth in each position. It’s a bit of a double-edged sword, because guys would play injured because they were scared of losing their spot.

“The first thing he said was ‘I don’t expect you to win the comp, but everyone’s going to know they played us, and they’ve really got to play us to beat us’.

“He didn’t put expectations on us to win, he said ‘just go out and do your best’ and that was really good for us, it took a lot of pressure off but it also helped build us up.

“Psychologically, he was brilliant, and that was the beginning of that cultural change.

“Come 91, we were playing every game with that attitude, but we had Pat Jarvis and Peter Jackson and Mario Fenech come along. We went to another level, then we started expecting to win.

“They’d have to bust their arse to beat us, with Mario and Pat’s toughness and a little bit of Jacko’s magic.

“Pat Jarvis was a bit of an unsung hero for Norths – he was at the back end of his career but he was so tough, so dedicated. The guys they got for us were perfect, round pegs for the round hole.”

Jarvis had come along in 1990, while Fenech lined up with the Bears the following year. They were two of the toughest players around, hard men for hard times, who never came across a rugby league problem that focused aggression and sheer desire couldn’t solve.

For Moore, Fairleigh and Larson, it was perfect. The Bears had the makings of one of the best forward packs in the competition already, now they had the right teachers.

“When we had those three new guys, they showed us through this murky maze, this myth of the Bears being losers,” Moore said.

“We wanted to punch our way through it, and those three were the light that showed us the way.

“I broke my jaw at the beginning of the 1991 campaign and I was wired shut for 14 weeks. While I was out the Bears won 12 of the 14 games they played, and I thought, at 19, that my career was over.

“Jarvis knew that, and when I do motivational speaking now I always pass on what the great Pat Jarvis told me.

“I was just about to get the wires out and come back, but I was still down in the dumps and he asked me what was wrong. This team was winning without me, and I said I deserved the jersey that a reasonable footballer called Gary Larson was wearing.

“He said ‘why do you think you deserve it’ and I said ‘I train hard’ and he said ‘mate, Gary’s trained harder than you’. He said ‘what you’ve got to remember is this – in life, you deserve nothing, it’s what you make and what you take. As soon as you think you deserve something in life you become weak’.

“So I went and trained with Johnny Lewis, became fitter, faster and stronger, and breaking my jaw and having Pat Jarvis say that was the greatest thing that ever happened to me.

“That’s the sort of bloke he was. He’d take a situation, sum it up, and he’d find something deep inside you that made you a better person.

“It was my reckoning, the key moment in my life, when I realised that when you go from average to good you realise it’s cause you don’t deserve anything.

“You have to make it and take it every day.”

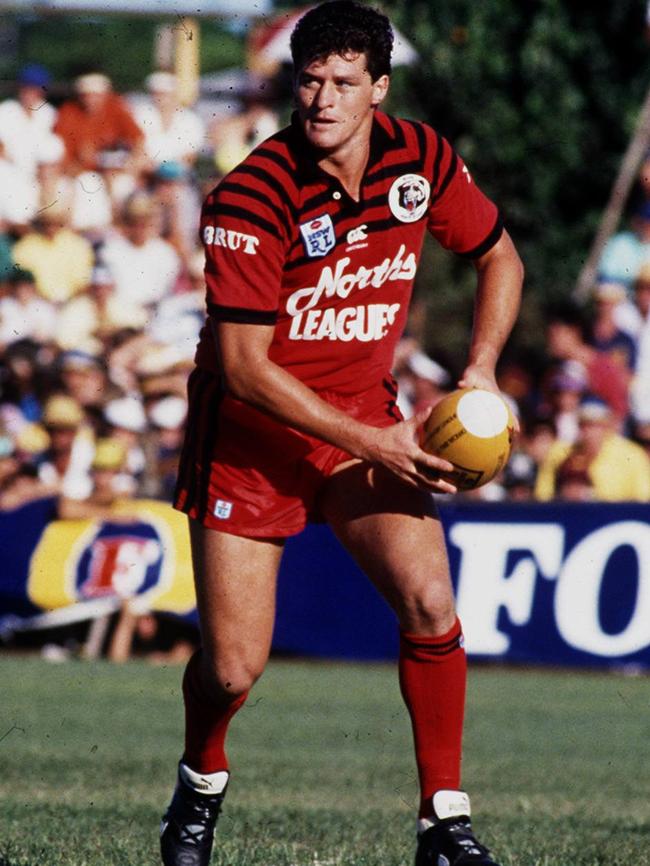

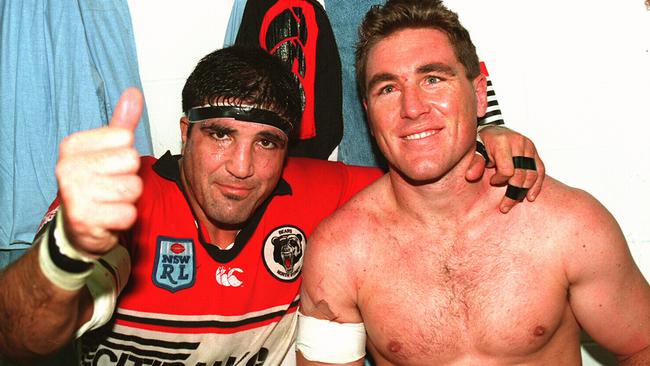

For Soden and Florimo, Jackson had just as big an impact. One of the game’s great characters, Jackson had no fear on a football field, and he gave the brutal Bears that little bit of swagger and class to match it with the top teams.

“Not just a brilliant player, he was a brilliant character, and he brought the club to life,” Soden said.

“Off the field it was suddenly a great place to be. Jacko was wild and crazy, but he’d still go out and play so hard.

“A million blokes could tell you a million stories about Jacko.

“That was the start of it. We were such a tight group of guys.

“The theory I’ve always had is it’s always better to learn than be taught and we were all growing and learning together, even the old blokes like Flo and Jacko. I love Flo, but he was learning to win again as well.

“He was our rock of Gibraltar forever, he was older than us but he was still one of us.

“We had a lot of fun off the field. We became such a close bunch of mates, and Jacko was a big part of that.”

Florimo and Jackson were best mates, and the Queensland Origin staple helped Florimo take his own game to the next level.

“Jacko brought some swagger, creativity, and the confidence to back yourself,” Florimo said.

“All three of them (Jackson, Jarvis and Fenech) had experience in big matches, it gave the people around a reason to listen to their message and get behind them.

“He was my best mate, we did a lot together. Our firstborns were born on the same day, so our families were close.

“I really learned from him on the field, and off it, on how to play the game, how to take charge and take a team around the paddock.”

There were other success stories for Norths in the Steve Martin days, diamonds in the rough where the Bears found some of the luck they’d gotten the rough end of so many times before.

For example, the Bears signed two fellas from New Zealand. One of them was Paul Simonsson, a former All Blacks squad member, a winger with speed and grace who was supposed to take league by storm. But injuries struck Simonsson down, so they threw in the other guy, a skinny fella from Waikato named Daryl Halligan, who went on to become one of the greatest point-scorers the sport has ever seen. In his first season with the Bears he was the league’s highest point-scorer with 196, breaking Fred Griffiths’ club record that had stood since 1965.

And so, with the toughness of their forwards, Jackson’s magic and Halligan kicking goals from all over the place, the Bears started winning. A lot.

By the halfway point of 1991 they were first on the ladder, looking down at the lot of them, and they’d cleaned up the two-time defending champion Raiders, and the new money blue bloods from Brisbane along the way.

The second half of the season kicked off with a showdown against the Panthers, second on the ladder and beaten grand finalists the year before. The Panthers got up, 8-0, but it was a seminal moment for the red-and-blacks.

“Mario Fenech and Adrian Toole’s heads smashed together and they both went off,” Moore remembers.

“Penrith won the comp that year, and we nearly beat them, we should have beat them, and we just didn’t quite get there.

“Steve Martin told us after the game – we wouldn’t go on any field wearing North Sydney jerseys, playing against anyone, anywhere, where we didn’t expect to win.

“There was none of this making up the numbers, none of this thinking that we’re not worthy and it’d be good if we got close.

“Steve Martin told us that day, from now on we expect to win every game.”

All of a sudden, after years of being on the other side, Norths were in the spotlight. They mattered again. There was no winning the premiership without going through them, no way to talk about the business end of the season that didn’t involve the Bears. That success flowed off the field as well.

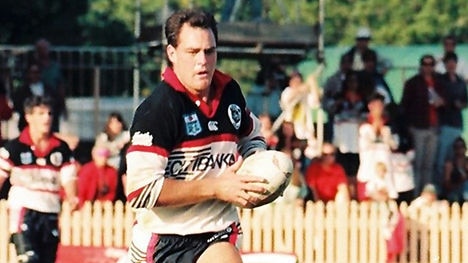

The Bears landed Citibank as a major sponsor, a massive get for any rugby league club, and were always in the news because David Hill, the charismatic president of the football club, was forever fighting the league’s partnership with cigarette companies. The punters flooded into North Sydney Oval, with average crowds at the grand old ground topping 15,000.

“David Hill, a very good operator, like him or not. As chairman of the ABC, having someone that powerful running our show (was a boost),” Soden said.

“He was pushing to stop the cigarette advertising, and what he was essentially doing was building a profile for North Sydney so players would want to come over, rather than Norths being the team nobody hears about.

“Then you start getting sponsors like Citibank, which was a huge coup. We were like the Citibank Bears.

“Then it snowballs, success breeds attention. We were a bunch of fresh kids who were really hungry and we didn’t have losing habits.

“We were all just going for it.”

Norths finished the 1991 regular season in third position with 14 wins. It set up a promoter’s dream, a clash with second-placed Manly at the Sydney Football Stadium on a glorious Sunday afternoon. The Bears had never played a finals match at league’s new home and Manly had all the confidence that comes from being to the manor born.

The last time the Bears had won a finals game in 1952, man hadn’t been into space, colour television didn’t exist and Dally Messenger was still alive. But Norths didn’t care.

Those were the old Bears that lost those games, and those losses left scars the new Bears didn’t carry. The future was theirs, and whatever happened back in the old days didn’t matter as much as was what was happening here and now, in the six inches in front of their faces.

“When we took the field against Manly, I know the fans hadn’t experienced success for years, but we just demanded it,” Moore said.

“We expected it. I knew we didn’t deserve to win, we were going to make it, and take it.”

Take it they did. Jackson played a blinder, scoring a try and throwing the final pass for Moore to get over twice. Manly fought hard, and Cliff Lyons starred, but a late try to David Hall put paid to any thoughts of a comeback and when the dust settled the Bears had won 28-16.

“I thought it was all coming together,” Florimo said.

“This was the right mix of players, and this is the formula of success. It didn’t feel unnatural, it felt comfortable cause of all the hard work we’d put in.”

It meant the following week they’d take on Penrith again in the preliminary final, with a grand final berth on the line. The ascendant Panthers were in the midst of their own fairytale, but the match wasn’t like anything from a story book.

Norths were tough and battle-hardened, as were the Panthers, but Penrith — led by Greg Alexander — had the Bears covered for individual brilliance. The Panthers shot out to a 12-0 half-time lead on the back of just that – Norths had the better of the first half, but couldn’t quite finish the job, while Penrith scored twice in the final five minutes before the break.

But come back they did. Panthers fullback Anthony Xeureb threw a suicidal pass in the shadows of his own line and Halligan snapped up the intercept to score and get them on the board. Penrith added a penalty goal, but Norths levelled up with two tries to David Hall, both set up by Peter Jackson’s brilliance, one from a kick and one from the Queenslander bursting into the clear from deep inside his own half, which levelled the scores with 15 to go.

“The opportunity was there. We had the confidence on the back of beating Manly. We were close, and in the end it was a penalty, a pathetic flop penalty, and that did us,” Moore said.

“It seemed pretty innocuous, but life goes on.”

Interchange forward Peter McPhail was the unlucky man who gave it away, Greg Alexander made no mistake from just off centre and the Panthers led 14-12.

Despite scoring three tries to Penrith’s two, Norths couldn’t kick clear and the problem was Halligan, who endured the worst kicking day of his career.

These days Halligan is a byword for clutch kicking. You’d trust prime Halligan to kick for your life without question. But back in 1991 he wasn’t that, not yet. He was a prodigious point-scorer to be sure, but his 63.72 per cent success rate for the year was the worst of his career by far – it was one of only four seasons in his decade in the top grade that he kicked below 80 per cent.

The Kiwi managed just one successful goal, missing conversions and penalties all day, including one from 40 metres out, close to in front, with two minutes left that would have levelled the scores. He finished the day with one goal from five attempts.

Three times in that first year did Halligan miss at least four goals in a match – over the next nine years, it only happened three more times in total. It was a rough day, but this was not the Halligan we would come to know.

None of the old Bears blame Halligan. They never would have made it there without him in the first place. But it still felt like a chance lost.

“As you go up the ladder, one thing you realise is what life gives you at the highest level is very few opportunities, and you have to take them,” Moore said.

“I’ve thought long and hard over the subsequent decades about why we were good and not great, and one of the things is because you’ve got to take your opportunities when they come.”

The consensus was that whichever team won from Norths and Penrith would win the grand final and the other would lose to Canberra, such was the physicality and the drama of the major semi, and that’s exactly how it went down. The Bears had nothing left for the Raiders the following week and fell 30-14.

The following year things just couldn’t click in the same way. The 1992 Bears still had the hunger and the expectations of success, but some years it’s not enough to be hungry.

Jackson, their attacking focal point, only managed 10 first grade matches and without him the Bears were still rough and ready, but easy to work out. Jarvis retired, and they missed him badly. Injuries meant they used 34 players, and a 52-20 belting from Souths in Round 17 ended their playoffs hopes five weeks out from the finals.

There were internal problems as well. Martin had done so much for the club, but cracks were starting to appear.

“With Steve Martin, the square peg-round hole theory fell out with a few people. It created a bit of a revolution, but not an evolution,” Moore said.

“It was disappointing that we didn’t go back to the finals, because we were such a good side. Jacko had a few injuries and he kind of dropped out of the team, and he was such an important player.

“But I climbed one of my Everests in playing Origin, and that helped me be a better player for the Bears, but for Billy Moore the Bears player it was a disappointing couple of years.

“What exposed us to that was going to State of Origin, once we got there it was a whole new pond of fish. Everyone was good. You watch Allan Langer, Kevin Walters and Steve Walters at training, you watch what they do and extrapolate off of that to what Brisbane are doing, what Canberra are doing.

“We realised we’d gone as far as we could on the journey with Steve. We had a no-pass policy in our own half – which is ridiculous, because what happens is other teams worked that out, and they aimed up on us and we were lambs to the slaughter.

“After a year we’d grown so much, as a group and as individuals, and we needed to keep that growth going. That wasn’t going to happen under Steve.”

The friction nearly tipped Moore out of the club – he signed a deal with Manly and only got out of it through the good grace of Sea Eagles coach Graham Lowe.

“It was a very quiet, hush hush deal. I played Origin and I couldn’t believe how good it was, I couldn’t believe the freedom of movement. I was playing with some great, great players, Jacko and I were rooming together. Steve Walters, Gary Belcher, Mal Meninga, the names, my God.

“Graham Lowe said to me ‘Billy, you’re fit enough and smart enough that you can play wherever you want. Just run around, you pick your spots’ and I scored a try, on debut, after 10 minutes.

“That came from the freedom he gave me. Graham knew things weren’t great at Norths so he asked if I’d be interested in playing that way all the time with Manly. I said I would, the offer came in, I signed, and then I realised Norths was where I wanted to be, and Norths were going to make some changes at the coaching level.

“I went to Graham and said if they wanted me to honour the contract I would, because I’m a man of my word, but Norths were making some changes and I’d much prefer to stay.

“He said there’s no way they’d keep me if I didn’t want to come – basically, he and I wrote the contract, then he and I tore it up.”

Martin announced his resignation two days after that loss to South Sydney with reserve grade coach Peter Louis to take the reins.

Louis’ reserve grade side, spearheaded by Craig Makepeace, Noel Soloman and clever ball-playing forward Craig Wilson, were a crackerjack bunch who lost just two matches all year, and downed Balmain in the grand final for the club’s third reggies title in four years.

Martin had completed the framework he’d worked so hard to build. There was strong competition for spots all over the club, but reports from the time hint Martin was reluctant to use Louis’ stars.

Soden speaks especially highly of Martin, as a footballing mind and as a man, but agrees a change had to be made.

“He had a rating system, as soon as you’d get to training on Tuesday you’d run up to see what your mark was.

“You had your game rating and your competitive rating, so even if you hadn’t played great he’d know you competed well. He picked on those ratings, but as we were evolving the ratings weren’t.

“He shot himself in the foot a little, because he didn’t evolve when we did. I love the bloke, he changed my life in a lot of different ways – but his ego got a bit too big. He thought he had it all sorted. He was a great coach, and we just wanted him to pull back a little bit.

“Years later I had a crack at him, I hadn’t spoken to him for 20 years. I went round to his place for a coffee and said ‘I’ve got big issues with you’ and he said ‘what?’

“I said ‘if you sorted it out we’d have won a grand final, we’d have gone to Super League and we’d still be around’ and he said ‘yup, you’re right on both’.”

The Bears took to Louis immediately. In 1993 they won eight, drew one and lost one of their first 10 matches to once again sit top of the ladder at the halfway point of the season.

They retained their hard edge, but had a new flair and freedom of expression. Louis was a different beast to Martin – more relaxed, and comfortable enough to take on a player’s suggestions or ideas.

Case in point came when Brisbane visited North Sydney Oval in Round 9 of that year. It was a top-four battle, and the Broncos had all the prestige and star power that comes from being the defending premiers. Playing against the Broncos wasn’t like playing against other teams, and a bumper crowd packed into the ground to see if their Bears were even better than the real thing.

During the week, Moore and Fairleigh approached Louis with an idea of focusing all their attack on the fringes of the ruck, where they believed Brisbane were vulnerable. Go for it, said Louis, and the result was a 40-20 smashing, the biggest defeat the Broncos had copped in their short history, with Fairleigh earning man of the match honours.

“We haven’t had that sort of freedom at Norths in the past, and it was great to be given that vote of confidence by the coach,” Fairleigh told Steve Ricketts in The Courier-Mail at the time.

It was just what they needed, and the unheralded Louis, who’d never coached a first grade side before, proved to be the perfect man for the job.

“He allowed us to control our destiny, cause he didn’t see player input as a threat, but as an asset,” Moore said.

“We moved from the square peg-round hole theory, to not needing to conform. He’d say these are the skills you have, this is where we want to be, let’s find a way to get there together.

“There were still consequences if you didn’t deliver, but it was another growth phase. In 24 months we’d gone from not being finals contenders to being in the top echelon.”

Despite the strides they made under Louis, the 1993 Bears didn’t make a return to the finals through a bizarre set of misfortune. They won 14 games (as many as they did in 1991), only lost by more than 12 points twice and over the course of the season they beat every team that made the top five.

It had been five years since a team missed out on the finals with at least 14 wins, but miss out they did – watching those same Broncos they’d belted earlier in the year go on to win the premiership from fifth.

There was the consolation of another reserve grade title – with Soden at halfback after he struggled to crack first grade, and Jackson at five-eighth after he managed just three matches in the firsts all season.

Jackson kicked the winning field goal in the 5-4 grand final win over Newcastle and retired, but his impact on the club in just three seasons was profound and lasting.

“That’s when I learned that things happen for a reason, and I always thought if I put on a jumper for North Sydney I had to play as hard as I can for them because Jacko was doing the same,” Soden said.

“I was talking to Jacko in the stands after the game. It was Matty Johns’ breakout year in first grade and I said ‘I gotta tell ya Jacko, that Matty Johns’s brother – Andrew I think it is? – he’s going to be a great player’.

“I went over to the other change rooms to congratulate him, because you could just tell how great he’d be.”

The Johns brothers would soon propel Newcastle into premiership contention, and the superpowers of the age – Brisbane, Canberra, Manly, Canterbury – were all still flexing their muscles.

The Bears weren’t the laughing stock anymore, but they were a club at a crossroads. The pieces were all there, they just needed someone to bring them together. They expected success, but 1991 was getting further away all the time. There were some final steps that had to be taken.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout