Greatest Ashes comebacks: Don Bradman’s captain’s call, Ian Botham’s Headingley heroics and the summer of Mitchell Johnson

IT’S never over until it’s over. Six jaw-dropping comebacks from Ashes history, featuring Sir Don Bradman, Ian Botham and Mitchell Johnson 2.0.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Ian Botham defies the odds (500-1 to be precise)

When England went through their long fallow period in the Ashes from the late 80s to 2005, it is no exaggeration to say that memories of the ‘Botham Ashes’ of 1981 went a long way to sustaining them, as humiliation upon humiliation was endured.

Not only was it one of the most incredible of series, but gave the battered Poms belief that even when all hope appears to be lost, there is always a chance.

ASHES COUNTDOWN : Days 50-41 from our daily nostalgia fix

ASHES COUNTDOWN: Days 40-31 from our daily nostalgia fix

ASHES COUNTDOWN: Days 30-21 from our daily nostalgia fix

ASHES COUNTDOWN: Days 20-11 from our daily nostalgia fix

In this instance a chance priced at 500-1 by local bookmakers, value too good to turn down for Dennis Lillee and Rod Marsh, who dispatched a staff member to the local Ladbrokes office to stick a tenner on the result.

There is no suggestion of any nefarious motives held by the pair, just, as sportsmen, knowing that offers like that don’t come round often, and are always worth a tickle.

Especially, as it turned out, with Ian Botham and Bob Willis on the field.

Botham had been relieved of the captaincy after the previous Test — a draw in which had left Australia 1-0 up in the series — replaced by Mike Brearley.

Perhaps freed from the burden, or with a point to prove, Botham took six wickets as Australia declared at 9-401, and then made 50 as the hosts were rolled for 174.

England fell to 5-105 in their second innings — the point at which those match odds flashed up on the big screen at the ground — requiring a herculean response from Botham and England.

Which duly arrived.

“I just thought if we go down, let’s go down burning,” he said.

A slightly fortuitous 56 from Graham Dilley allowed Botham the time to plunder 149, the century coming off 87 balls.

Australia needed 130 and were cruising at 1-56. Bob Willis, a lanky fast bowler with shot knees, changed ends and grabbed amazing figures of 8-43 as Australia collapsed 18 runs short.

England players the series 3-1 and went from perennial laughing stock to national heroes. For a short time at least.

Amazing Adelaide lives up to the billing

Ricky Ponting talks of it as one of his fondest memories from playing the game. England still carry the scars of it every time they visit South Australia.

Amazing Adelaide: where a meandering run-heavy draw can suddenly morph in to a sudo-Twenty20 slugfest in front of a baying full house on a Monday.

As bat dominated ball in to near submission in the opening four days of the 2006 Test, both teams piled on the first innings runs, England declaring at 6-551 (including a double ton from Paul Collingwood MBE) before Australia’s reply was just 38 runs short.

By close of play of day four, England had stretched their lead to 97 for the loss of a single wicket. You couldn’t find a bookie to take your money on a tie.

Step forward Shane Warne, who bamboozled Andrew Strauss and Kevin Pietersen on route to second dig figures of 4-49 from 32 overs. In all England’s last nine wickets fell for 60 runs.

At tea Australia’s batsmen contemplated the 36 overs in which they had to knock off the 168 to win. The discussion presumably a short one.

All out attack the order of the day — Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer hitting 13 off the first two overs to get things up and running.

As the first two men fell, Michael Hussey was shuffled up the order to maintain the momentum, he and Ponting creaming the terrified English attack to all areas, boundary after boundary.

By now the locals had got wind of what was happening at the ground and had poured in, building pressure on the bowlers and adding a delirious carnival feel to proceedings as the improbable shifted in to the possible and then all-but certain.

With Australia cruising, some jeopardy was reinjected as Ponting and Damien Martyn fell in quick succession. First innings centurion Michael Clarke (21 no) joining Hussey with the equation 47 needed off 58 balls. Too easy. Clarke was an able foil but Hussey (61 no) got the job done, heaving the winning runs with a scarcely credible three overs to spare.

The euphoria of winning an unwinnable Test carried Australia on to an emphatic whitewash and swift payback for 2005 and all that.

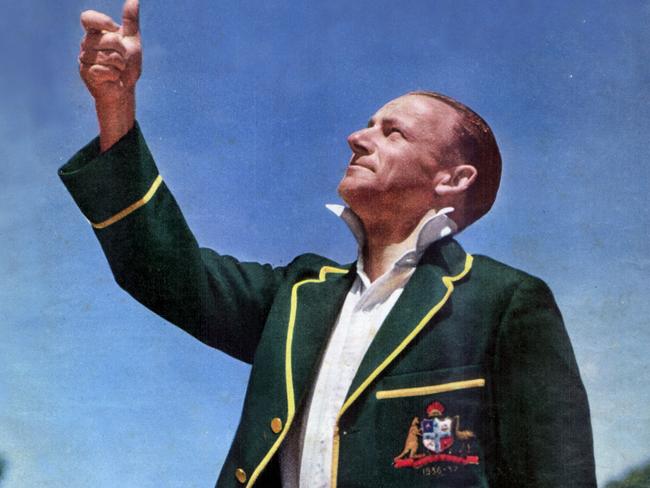

Bradman becomes captain creative

Though Sir Don Bradman now inhabits a place within cricket folklore in an elevation all of his own, there was a time when even he was under pressure, when things were on the verge of unravelling.

The response was to make a bold and inspired series of calls to turn the fortunes of his side around, while, naturally, playing a personal innings of substance to do much of the heavy lifting off his own bat.

Two matches in to the 1936-37 series and Australia were on the ropes. A 332-run victory in Brisbane and an even more emphatic win by an innings and 22 runs in Sydney had the tourists 2-0 up heading in to the Melbourne Test.

Bradman won the toss but, after electing to bat he fell for just 13 on a first day in which Australia’s pain was only ended early by rain, with the score 6-181 on a batter friendly track.

When play eventually started late the next day, the pitch was a swamp, Australia slogging their way to 9-200 before Bradman declared.

On the same minefield, England tumbled to 7-76. But Bradman was not entirely pleased, it was all happening too fast, he did not want to be batting again on such a surface so soon.

In the end England ended their own innings early, at 9-76, with 45 minutes to play and a chance to get at Australia.

Bradman responded with another masterstroke, inverting the batting order, tail-enders now openers, to protect the true batsmen — himself included — from the worst of it. As the light drew in under stormy clouds, England got through just three overs before the game was paused for 36 hours, the Sunday a rest day.

On Monday morning the sun was out but the pitch still damp. Bradman continued to serve up the less able to play for time as the pitch dried.

Midway through the afternoon Bradman strode out at an uncustomary no. 7, with Australia 221 in front and half their second innings wickets down.

Between the showers Bradman made 56 that day. In better conditions the next he kicked on imperiously to 248 at the close, 270 as he fell the following morning, exhausted: at seven and a half hours his longest knock, and still a record score for a No. 7, even if he was that only for one innings.

England fought hard to respond but a score of 323 left them still 365 in arrears when the match concluded.

“Some were unkind enough to suggest that my purpose was to avoid batting on a wet wicket,” Bradman wrote later of his self demotion down the order.

“Of course it was; but only because such avoidance was necessary in the interests of the team.”

Bradman himself rated others more highly but Wisden has since, by means of a complicated set of parameters, defined it as the greatest innings ever played by anyone.

Regardless of its historical worth, it was enough to turn the tide of both the match and the series.

Australia dominated the next two Tests, winning by 148 runs and an innings and 200 runs to win the contest 3-2 from 2-0 down, Bradman himself contributing another double ton in the fourth Test and a mere 169 in the decider.

Geoffrey Boycott ends his self-imposed exile

The name Boycott is virtually a synonym for bloody-mindedness. A student of the art of pragmatism, whole summers felt like they passed between his boundary shots.

And yet few batsmen knew how to occupy the crease, and time, like he did, and though they mostly came in ones and twos, over 100 first-class centuries tell a story of someone which any side would be grateful to see at the top of their order.

It was his obduracy that saw him miss 30 odd Tests in his prime, when he went on a self-imposed exile from the England team in 1974 due to his unhappiness with Mike Denness’ captaincy.

His comeback came at the ground where he had made his international debut, Trent Bridge, and the mood was less than receptive, many in the home stands almost willing him to fail.

That ill-feeling towards him only grew after he committed the sin of running out popular Nottinghamshire player Derek Randall. Though Boycott insists “Randall didn’t run quick enough,” the 37-year-old returnee was most to blame with the call.

With the Australian bowlers working him over, and his own home ‘fans’ now resolutely against him, Boycott did what he did best: dug in and ground his way to three figures, his 98th ton.

By close of play all was forgiven. In the second knock England needed 189 to win the match and go 2-0 upon the series. Boycott claimed 80 of them without giving up his wicket, and was at the crease when, appropriately, Randall hit the winning run.

The pair walked off victorious, arm in arm, Boycott’s rehabilitation in the eyes of the supporters complete.

Boycott, who had batted on each of the five days of the Test over 12 hours, then went on to claim his 100th first-class century in the fourth Test, 191 at his home ground of Headingley, as England won the five match series 3-0.

Mitchell Johnson silences his most vocal critics

On Australia’s tour of England in 2009 Mitchell Johnson looked a broken figure. Asked to provide leadership for what was a poor Australian attack, the weight on his shoulders was too much to bear.

The merciless English fans smelt blood. Johnson became a lightening rod for their taunts, the infamous song about his errant radar only increasing in volume as its inelegant chorus proved more and more apposite.

A sensitive man away from the pitch, at odds with the role asked on him in the middle, his talent was never in question but consistency was an issue. As was self confidence, a reason the sledging was so effective against him.

The home loss in 2010-11 offered no respite before he was dropped from the side entirely for the 2013 series in the UK. A toe injury put him out of action for seven months. A further blow? No, “the best thing that ever happened to him,” according to Johnson’s father.

A period of time out of the cricket bubble; an opportunity to work on fitness and a remodelled, extended run in; the pressure removed when England came back to Australia in the summer of 2013-14.

What happened next could not have been any more perfect a response to the Barmy Army had that trumpet been shoved somewhere very uncomfortable for its owner by Johnson’s own hand.

Three man of the match performances, 37 wickets at under 12, a whitewash in which he almost single-handedly ended the careers of Graham Swann and Kevin Pietersen.

But more than that was the glorious sight of a broad grin beneath that fulsome moustache as he charged in at Brisbane and didn’t let up until close of play in Sydney.

A one man wrecking ball of angry energy, slaying almost as many demons as he did Poms.

An ageing Bradman proves fit for purpose after all

After he uncharacteristically scratched around to a score of 28, England thought they had snagged the prized wicket they wanted most, Bradman apparently feathering a delivery and caught at slip.

But as the visiting side celebrated, Bradman was unmoved. The umpire found in his favour, declining to raise a finger. It was to prove a decisive moment in an unlikely personal comeback, even for the peerless Don.

The match at the Gabba, the first Test of the 1946-47 series, marked Bradman’s return to the Test arena after the interruption to sport of global conflict, aged 38 and, by all accounts at the time, looking physically diminished from his last appearance, some eight years prior.

Invalided out of the army in 1941 with fibrositis, he had been deemed too unwell to tour New Zealand earlier in the year. And yet he declared himself fit for the Ashes and was handed the captaincy as post-war cricket resumed in earnest.

Despite his less than peak condition — and even wearing a borrowed Baggy Green for the match — after being given a life of sorts he cashed in, going on to score 187.

Australia duly won the match, and the series 3-0, before two years later Bradman led his legendary Invincibles on the tour of England in which the side went unbeaten and he recorded his infamous final innings duck.