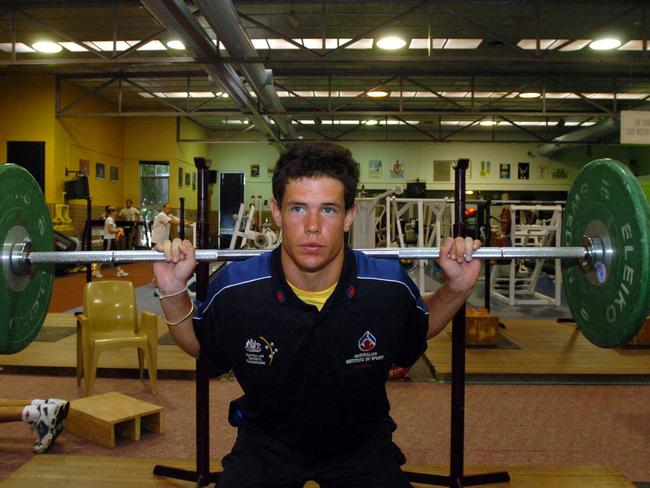

Former Mariners and Jets star Troy Hearfield opens up on what might have been

One drink was all it took. One Jack Daniels and Coke, downed in one. One Jack Daniels with a tab of methamphetamine in it, and in a moment an Olympic career was snuffed out.

- Part One: Dylan Tombides’ legacy will live on

- Part Two: How the system chewed up the ‘next Harry Kewell’

- Part Three: From Liverpool and Man U to tech career

- Part Four: How Stuart Musialik emerged from a dark place

The world was at their feet — young Australian footballers blessed with talent before life took a twist. TOM SMITHIES continues our series looking at players whose careers ended too soon

ONE drink was all it took.

One Jack Daniels and Coke, downed in one.

One Jack Daniels with a tab of methamphetamine in it, and in a moment an Olympic career was snuffed out.

After more than 100 appearances in the A-League and five for the Olyroos, it still haunts Troy Hearfield that his footnote in history will be as just the second player in the competition to fail a drugs test and the first to show the presence of what the drug authorities deem performance-enhancing drugs.

Six years have passed since Hearfield was banned for 15 months for taking methamphetamine. He never played again.

Until now he has never spoken about his fall from grace, not least because for a period he was “in a very dark place”.

But remarried and approaching the end of a three-year carpentry apprenticeship, Hearfield wants to raise difficult questions around whether football owes a duty of care towards young men who make mistakes, even major ones.

WHEN his name was suddenly called out, Hearfield says he “didn’t have a care in the world”. He was 25, playing for the Mariners and having represented his country in Olympic qualifiers, when he was one of two players called for a random drugs test after Central Coast played at Melbourne Heart on October 28, 2012.

A phone call from the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Agency days later changed everything, inviting him to attend the opening of his second sample and provisionally suspending him after the first had detected traces of amphetamines.

When the second test confirmed that, Hearfield realised how much trouble he was in.

“It was devastation,” he said. “It was everything I knew, a young aspiring footballer. That was my life, my income, my family.

“I’m not going to sit here and say that I didn’t do the wrong thing. I shouldn’t have been drinking that night, I shouldn’t have drunk from someone else’s glass.

“I’m a professional athlete and I own that decision. It’s taken me a while to get over that but here I am six years later.”

HOW he came to test positive is laid out in devastating detail in the tribunal judgment that in May 2013 banned him for 15 months, backdated to November 2012.

Hearfield’s sister had arrived at his house unexpectedly from interstate on October 26 to celebrate his birthday, and between them they drank a bottle of bourbon.

In their evidence, both brother and sister said that she put the drugs in her glass secretly but then went to the toilet, at which point he picked up the glass and downed it.

Two of the tribunal’s three members concluded he had “made a foolish decision to accept illicit drugs from his sister after he had a considerable amount to drink in circumstances where his better judgement did not prevail”.

The penalty handed down could have been considerably higher, but the tribunal accepted the drugs were not meant to be in any way performance enhancing and reduced it to the statutory 12-month minimum plus another three months.

But Hearfield’s career was over. His agent, Tony Rallis, says he contacted a variety of clubs once his ban was over and none felt able to give him a trial, let alone a contract.

“My ban was up and I was training hard for when that day come,” Hearfield said. “For the next year Tony tried to get me a gig or even a training gig. Just eight weeks to prove myself. All of a sudden no one wanted to know who I was, for one mistake.”

THIS is the part of the story that raises those difficult ethical questions for the game. Hearfield had a reputation as a party boy, but he had also been worthy of playing more than 100 games by the age of 25.

In the A-League, the drug testing is carried out by ASADA under the global anti-doping laws and a failed test means a lengthy ban.

In the NRL and the AFL, the governing bodies run their own testing regimes in addition to ASADA’s mandatory checks. Players who fall foul of the in-house testing initially receive warnings and counselling, with the aim to catch drug issues earlier and allow players to receive help.

At the time of Hearfield’s offence there was little in the way of player-welfare infrastructure beyond the FFA’s MyFootball program, which was essentially to help players find jobs after football.

These days the welfare function has been passed on to the players’ union (PFA) with significant resources to help players with emotional, financial or any personal problems.

Hearfield says at the time there was no attempt from FFA to check on his welfare, and he believes he did not get enough support from within the game.

“I did the wrong thing, but the punishment I got was extreme,” he said. “I really worry about young players now. Imagine if this happened to another young fella, the welfare’s not there.

“Look at AFL and NRL, they get one, two or three chances. In football, if you stuff up, you’re gone. I was down for a very long time.

“It’s taken me six years but I put my family through hell. I’m happy now where I am and I’m grateful, but I really don’t want this to happen to any other young footballer.”

HEARFIELD isn’t comfortable about discussing how dark things got for him, though he says he “could never repay” his parents for their help in him coming out the other side.

“To this day Troy’s case gives me sleepless nights over how a young man’s career can be destroyed over one night on the drink,” Rallis said. “Ultimately, it cost him his marriage and several years of his life.

“He’d been tested eight times before and not been positive.”

Back in Tamworth, where he grew up, Hearfield is playing for the local club and enjoys the building work that has helped him get back to a normal life.

“But I sit and watch the A-League now and it feels like I should be still playing,” he said. ‘I made a mistake, but did I deserve to lose my career?

“The hardest part is coming to terms with what I could have achieved. I’d won two premierships within the game, with the Jets and the Mariners. But I lost all direction.

“Football was my first love. That’s what’s hard. I let a lot of people down around me.

“My sister still means the world to me.”