Diego Maradona had the most colossal strength yet some of the worst of human frailties

It was a life of genius, havoc and excess. Matt Dickinson - who spent more than two years researching Diego Maradona’s life for a book - pays tribute to one of the greats.

Football

Don't miss out on the headlines from Football. Followed categories will be added to My News.

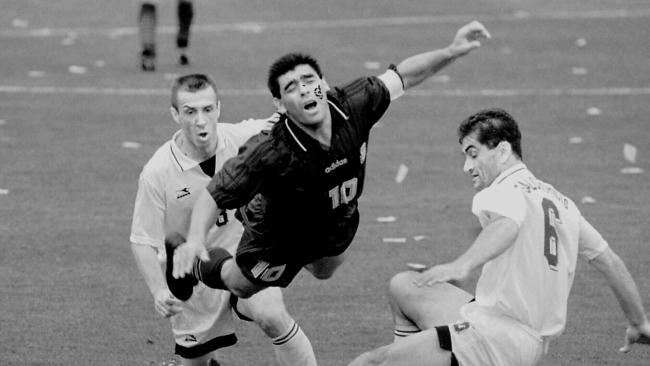

That he had such peerless control of a ball, and so little restraint over much of the rest of his existence, made Diego Armando Maradona arguably the greatest and definitely the most compelling footballer that ever lived.

In Maradona we found colossal strength yet some of the worst of human frailties; beautiful miracles and self-destructive wreckage; a strikingly handsome man who could swell grotesquely; who could bring delight to millions across the planet yet cruelty to those closest to him.

On Thursday the world mourned the death of the player, the icon, at 60 - but it could also celebrate that he packed 10 lives into that time.

Kayo is your ticket to the best sport streaming Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Get your 14-day free trial & start streaming instantly >

MARADONA DEATH NEWS

‘An eternal genius, a void that will never be filled’

Of course, Englishmen are not meant to be captivated by Maradona. We are meant to be repelled and some, even now, are still holding a petty grudge. Pathetically.

I spent more than two years researching Maradona’s life for a book, Maradona Opus, due to be published in March - he was meant to come over to help launch it - and the closer I got to him the more I was transfixed.

He did not always make it easy to admire him. All was arranged to interview Maradona at his home in Buenos Aires, to reflect on his life’s glory and chaos (no shortage of either). But Diego is Diego. Greatness, like royalty, gives you certain privileges, including the ability to keep people waiting indefinitely - as we did for an entire day only to find out that he had vanished into the night.

We flew back another time, all the way to the Argentine capital, to meet him. Again, he had a better offer.

To finally catch up with him was worth those air miles and cancellations. Most of us spend our lives compromising, conforming, fitting in. Maradona oozed outrageousness, rebellion, fearlessness. He was 5ft 5in but with a towering personality.

To meet him - to talk about goals and drugs, grasping the World Cup and how the love of his daughters dragged him back several times from the brink of addiction and death - was to be captivated not only by his achievements but by an extremely rare life force.

My favourite photograph of Maradona shows him gazing murderously along the line of players before Argentina’s classic confrontation with England in 1986. It is the face of a leader - not only of a team but of a nation of more than 30 million people - who was going to shape history that afternoon, whatever it took.

Genius? Cheat? Think what you like of Maradona, but to have visited Villa Fiorito is not the only reason - though it remains a very good one - why I have always found myself celebrating the man and his life.

MORE NEWS

‘Greatest of all time’: Maradona dead

Maradona’s fall: Mafia, sex workers, drugs

I wrote about that trip recently, as Maradona battled a bleed on the brain that we thought he had overcome: about the shanty town outside Buenos Aires where he was born and raised, the best place to start understanding the phenomenon.

I stood in the dilapidated single-storey shack at 523 Azamor. This was where, legend has it, Maradona was hauled out of an open sewer by an uncle, stinking of crap. To stand in that lowliest of settings and imagine that a kid could climb from here to reach the top of the world, whose death could spark such a global outpouring of grief and reverence, was mind-boggling.

What talent, what drive, what spirit to elevate yourself from this barrio to a sporting deity, to champion of the world.

It was a journey that took Maradona to places he could never imagine - or prepare for - which is why I left Villa Fiorito with a new sense of understanding and, yes, sympathy, for some of the mayhem and madness that was to come.

As a biographer, tracing his journey is like coming across the aftermath of a series of wild parties. A huge amount of fun has been had but there are piles of wreckage left to sift through.

Genius, havoc, excess. That is the Maradona effect, always leaving some sort of unforgettable memory and, yes, sometimes an ineradicable stain.

For a man of extremes, Naples always was going to be the best and worst place for Maradona to move to; an area of volcanoes, eruptions and earthquakes; a city with a dangerous edge; a downtrodden region in need of an iconoclastic hero. Maradona fitted right in.

I visited the city on the bay several times to gain a sense of the impact Maradona had there between 1984 and 1991, including the shrine for him on one street which supposedly contains a strand of his hair.

This was the city where, as he led the club to two Serie A titles against the might of AC Milan, they put a sign up on a cemetery wall saying, “You don’t know what you’ve missed”. Someone scrawled a response: “How do you know we missed it?”

If he could not raise the dead, he could make you believe in miracles.

Arrigo Sacchi, the revered coach of Milan, explained to me how Maradona claimed to have struck a free kick with such accuracy that he deliberately flicked Ruud Gullit’s dreadlocks on the way into the top corner. A boast too far? Sacchi said that he would not have believed it from anyone but Maradona.

Rivals did not have a bad word to say about him, even knowing that Naples was where his cocaine addiction began to take its pernicious hold.

Like me, they were rather ambivalent about that vice, understanding that Maradona was not taking the white powder to boost his extraordinary skills. Quite the opposite. “Drugs made me a worse player, not a better one,” as Maradona had always argued. “Do you have any idea the player I would have been if it weren’t for the drugs?”

His club willingly protected him, even helping to cover up his dope tests, but eventually Maradona would be cut adrift by Napoli, and his Mafia friends, as captured in Asif Kapadia’s excellent documentary. A positive drug test and a 15-month ban was the beginning of a precipitous descent which would eventually bring him close to death in 2004 for the first of many round-the-clock vigils.

To understand the scale of devotion in Argentina, I went to a gathering of members of Iglesia Maradoniana - the Church of Maradona - formed by his most fanatical fans. The occasion was Maradona’s birthday, October 30, which is Christmas Day for this particular religion. There was a crib, and you can guess who was Jesus, clad in a No 10 shirt, with Johan Cruyff, Pele and Alfredo Di Stefano as the wise men paying homage.

Dalma, Maradona’s eldest daughter, once agreed to attend a meeting of the Iglesia Maradoniana in a restaurant. Half a dozen devotees suddenly appeared in white tunics, holding a rosary like they were in church. They chanted that Maradona was a saint.

“Then two people got married using El Diego, my dad’s autobiography, like it was a Bible, placing their hands on it,” Dalma explained.

“It started to get embarrassing when they began to worship me. They are really nice, good people but I told them they are crazy.”

Such craziness was the norm in Maradona’s life. To watch him being mobbed any time he left his house is to think of today’s superstars: one-man corporations with their battalions of lawyers, PRs, agents and security guards.

Maradona was in the jungle, fending for himself.

Fame corrupts and, of course, it led to some appalling behaviour. In his private life there was the son born to Maradona in Naples, whom he denied for years. In his professional life, there would be the disgrace of the positive test for ephedrine at the 1994 World Cup, which he still insists was a conspiracy cooked up by enemies at Fifa.

But to talk to his teammates was to hear how they would follow him to the ends of the earth. Sergio Batista, a teammate at Argentinos Juniors then with the national team in 1986 and 1990, explained how Maradona had helped him through his own bouts of addiction. He talked about Maradona’s impact as a friend as well as a leader. “I can tell you that he gave me much more than he took back,” he said.

And it is not as though Maradona ever claimed to be a saint. In our interview, which eventually took place at a hotel in Madrid, he was at pains to dismiss the idea that celebrities should have to carry that burden.

Parents, he said, are role models, not footballers or pop stars. He may apologise to his daughters, Dalma and Giannina, for the errors and regrets of his life but the rest of the world could forget it. “I made mistakes, and I paid for them,” he said.

His last miracle was to survive until he was 60. That felt typical of the defiance, the life force, the spirit that was as essential to the success of Argentina and Napoli as his talent.

And what a talent. Billions kick a football but Maradona could do it perhaps better than anyone who ever tried. That, surely, is how we remember him.

On his television show, La noche del Diez - “The Night of the Ten” - in 2005, Maradona mused about his epitaph. He talked about his gratitude for being able to play the game, the sport that “gave me the most joy, the most freedom, like touching the sky with my hands”.

In conclusion, he said, he would want his gravestone to include the inscription: “Thanks to the ball”.

We should give thanks to Diego Maradona, and football’s most epic life.

Originally published as Diego Maradona had the most colossal strength yet some of the worst of human frailties