The most bizarre World Cup innings ever: Sunil Gavaskar carries his bat … for 36no

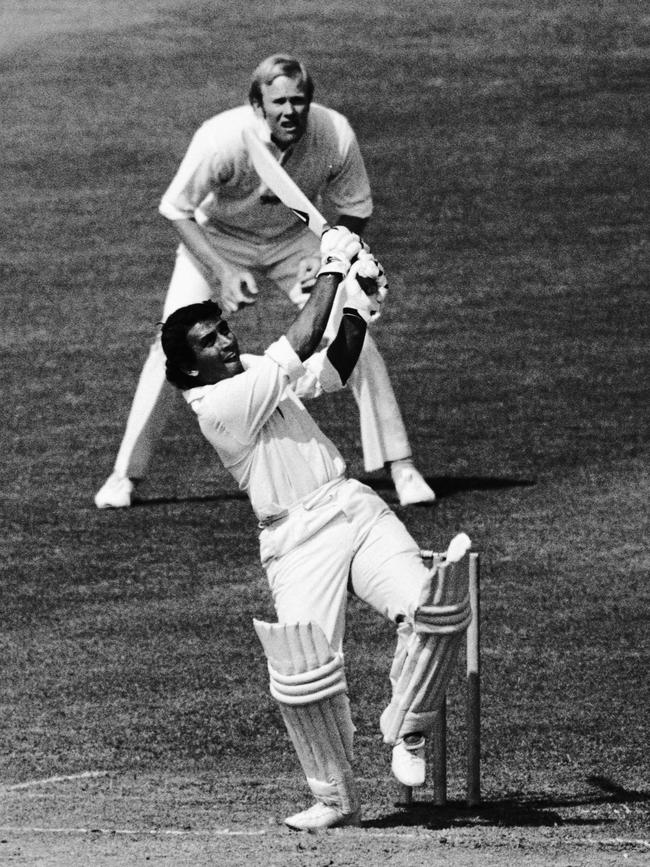

In the first ever Cricket World Cup match, between England and India, Sunil Gavaskar carried his bat. It was not, however, in a winning cause. Not even close. Was he playing for a draw?

- Jonty Rhodes on the photo that changed his life

- World Cup team guide: In Kohli India trust

- World Cup team guide England expects

When India and England meet at Edgbaston at the end of June this year, should Rohit Sharma or Jonny Bairstow carry their bat, the record books will almost certainly need a rewrite.

With England regularly breaching the 400 barrier of late and India boasting a formidably productive top order, one of their big hitters being at the crease for the full innings would mean runs, runs and more runs.

It hasn’t always been thus. Certainly not in the first ever World Cup match played.

When India lined up against the host nation at Lord’s in 1975 it was only the visitor’s third taste of the new format, which had seen its international debut just four years prior.

That and their billing as rank underdog may have clouded Indian thinking. None was more hazy and unclear than Indian opener Sunil Gavaskar.

DEFENCE THE WORST SORT OF ATTACK

England batted first. And posted a then record score — from an admittedly small sample — of 4-334 off their 60 overs.

The bulk of the damage had been done by Dennis Amis (137) and Keith Fletcher (68), closed out by a spectacular, by modern or contemporary standards, 51 off 30 balls from Chris Old.

It was a match winning total. One that India was never likely to chase down.

Still, in a four team group run rate might come in to play and so there was merit in India having a dig, both tactically and for the sake of the thousands of fans they had in the stadium.

A simple, obvious thought. But one that did not enter the mind of Gavaskar, who went on to play one of the most bemusing and curious innings played at that or any World Cup since.

The Indian opener batted, quite simply, as if playing for a draw. Eating up the overs and showing no sign of risking anything for a shot at an improbable chase. He finished 36 not out from 174 balls faced, including a single boundary.

India finished their innings 3-132. A losing margin of 202 runs.

Indian team manager GS Ramchad had initially said Gavaskar would avoid any censure for his ‘efforts’, but came out stronger a few days later after a poisonous public inquest.

“It was the most disgraceful and selfish performance I have ever seen,” he said. “His excuse was, the wicket was too slow to play shots but that was a stupid thing to say after England had scored 334. The entire party is upset about it. Our national pride is too important to be thrown away like this.”

THE SEARCH FOR MEANING

The search for understanding saw numerous explanations weighed in the court of public opinion.

Was Gavaskar in a funk after being overlooked for the captaincy in favour of Srinivas Venkataraghavan? Or showing his displeasure over a team selection that had gone against his wishes with the drafting in of pace bowlers to replace his preferred reliance on spin?

Did he simply and improbably just not understand the rules of the still new format of the game?

On India’s previous visit to the home of cricket, for a Test match, the tourists had been routed. With victory out of reach again, the suggestion was made that Gavaskar simply played conservatively to avoid another outright humiliation. A curious assertion when, during his infamous innings fans were repeatedly seen trying to storm the pitch to remonstrate with him and the team on the balcony visibly unhappy.

Only one man, of course, could settle the debate.

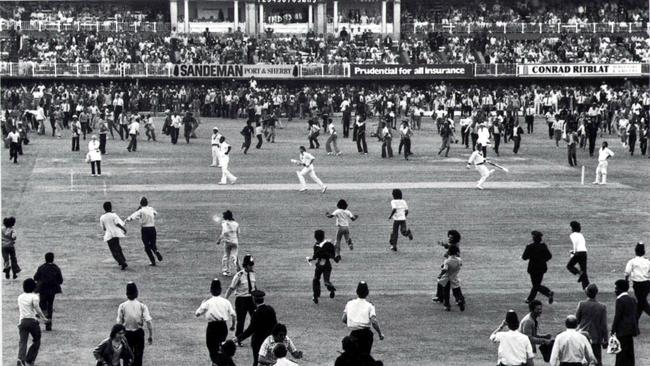

And he refrained from doing so, at least in the immediate aftermath of the contest, keeping his counsel for the remainder of the tournament (which recovered from its opening night misstep to produce a thrilling final in which the glorious West Indies side of the time proved too strong for an equally impressive Australia).

NO WAY OUT

Looking back years later Gavaskar offered some sort of light on his muddled state of mind. Though admitted even he was at a loss to understand, much less justify what had happened.

“It is something that even now I really can’t explain,” he said.

“If you looked back at it, you’d actually see in the first few overs some shots which I’d never want to see again — cross-batted slogs. I wasn’t overjoyed at the prospect of playing non-cricketing shots and I just got into a mental rut after that.

“There were occasions I felt like moving away from the stumps so I would be bowled,” he confessed. “This was the only way to get away from the mental agony from which I was suffering. I couldn’t force the pace and I couldn’t get out.”

He has also since expressed regret at not exiting the scene at one opportunity presented to him. A nick off an early delivery that carried to the keeper but was so faint as to avoid eliciting an appeal. He considered walking, but was not offered enough encouragement and the escape route was closed before he could act.

“That little moment of hesitation,” he said, with a heavy dose of understatement, “got me so much flak all these years.”