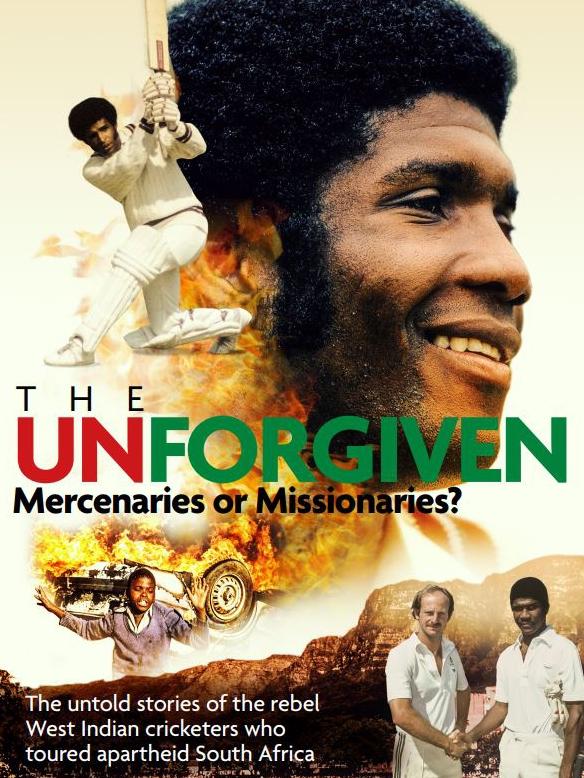

How the West Indies’ rebel tours to South Africa left the lives of some cricketers in absolute ruin

He had the silkiest hands in cricket. But David Murray’s life fell apart after he made a $100,000 call to turn his back on the West Indies and tour apartheid South Africa in 1983.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Wicketkeeper David Murray was a member of the 20-man West Indian rebel cricket team to visit South Africa in the early 1980s, but like several men on those tours, his life fell apart.

In The Unforgiven, Ashley Gray reveals the untold story of Murray and his rebel teammates.

*********

At the Stadium Road Bar & Restaurant, a rum shack opposite the crumbling National Stadium on the outskirts of Bridgetown, Barbados, Collis King is living up to his reputation as the great entertainer of West Indian cricket, reeling off rum-soaked anecdotes in the same cavalier fashion he dominated bowlers.

David Murray sits beside him at the outdoor table, his anxiety dimmed by several glasses of Mount Gay dark rum and tonic.

He is clearly enjoying being close to a man who has shared much of his cricket journey, but little of the hardship.

Stream over 50 sports on-demand with KAYO SPORTS on your TV, computer, mobile or tablet. Just $25/month, no lock-in contract. Get your 14-day free trial and start streaming instantly >

King is a big guy. He can handle his alcohol. Murray cannot. He is soon clutching his old teammate’s hand, gibbering “I love you, man”.

It’s obviously a heartfelt sentiment but after a dozen admissions, King gently takes Murray’s hand and repositions it on the bench.

An incomprehensible low-level burble is all Murray can manage for the rest of the night.

*********

Malcolm Marshall described David Murray as the best, most agile wicketkeeper he played with, the only one he could rely on to snaffle every half-chance off his bowling.

Joel Garner said he would trust Murray to keep for his life.

Even Jeffrey Dujon, who succeeded him as West Indies custodian, says Murray was a class above him behind the stumps — that he made him look like “Dolly Parton standing up to spin”.

But he only played 19 Tests over three years, sandwiched between the venerable Deryck Murray (no relation) and the flamboyant Dujon.

A lot of the rest of his life has been devoted to marijuana. Even on the cricket pitch and in a maroon cap.

“It was good meditation,” he laughs. “You could concentrate for real. First ball you say: ‘Good luck to everybody’, and then I’m on my own. The stronger it was, the more I would concentrate.”

But it was also, in part, his downfall.

MORE CRICKET

GAME CHANGER: INDIA OPEN TO ADELAIDE HOSTING TEST SERIES

CRASH: HOW A CRICKET TEAM BECAME THE MOST HATED OF ALL TIME

On the West Indies tour of Australia in 1981-82, just two Tests after bagging a West Indies record nine dismissals at Melbourne, he was ousted by Dujon for, among many things, failing to attend team meetings and turning up to the Adelaide Test without his gear.

Dujon recalls seeing Murray stoned at the old Camperdown Travelodge: “I said to him, ‘’D, we had a team meeting’, and he kept looking at the cars go by and said, ‘Yeahhh, you know’, He was as high as a kite.”

Distraught at being dropped, and with a young family and burgeoning drug habit to feed, Murray was the kind of easy target South African Cricket Union board member Ali Bacher knew to throw pots of krugerrand at.

But when Murray, son of West Indian great Everton Weekes, gloved up for the first time in the republic in 1983, the enormity of what he’d done — the life ban, the uncertain future — sunk in.

“(Captain) Lawrence Rowe at first slip said to me as a joke: ‘You can’t play for the West Indies anymore.’ It felt bad.” A tear rolled down his cheek.

“It was f…ed up,” he says. “They say things like ‘he sold his birthright’. You can’t play on certain pastures. They still do.”

He had money to burn — $US100,000 of it — and burn it he did, on women, fast cars and cocaine.

“I f...ked up,” he says. “I still smoke, but not like before. I just need a little smoke and I’m high. You just got to smell it now. I’m cool, my brother.”

He also mingles among what he calls the “chosen few”, wandering the tourist beaches near Bridgetown before returning to a family home in Station Hill, four doors down from an old prison, where he lives with two aunties.

*********

The following afternoon I call Murray to see how he is. We hatch a plan to meet at Pirate’s Cove beachside bar in central Bridgetown, then drive to see fellow rebel Alvin Greenidge (no relation to Gordon) at the Barbados Defence Force training ground.

Pirate’s Cove is a thatched palm leaf and cane affair gazing across the Caribbean Sea — a textbook tourist setup with hammocks and cheap Carib beer: the perfect spot for Murray to deal to his “chosen few”.

Watching Murray discreetly work the small crowd of European and local buyers, it’s clear he is on familiar sands. It is also clear he is not clean.

He shoots glances at imagined enemies and when he spots me, blurts out a desire to meet former Australian Test captain Mark Taylor because he is a “beautiful person who stopped his score on 334 out of respect for Don Bradman”.

It is the last coherent sentence he will make all night.

I’d planned to ask him about comments he reportedly made in South Africa claiming apartheid was not so bad, comments Aboriginal activist Charlie Perkins said should have precluded him from being allowed back into Australia.

But after drinking half a glass of red wine, he is too wasted to respond to anyone. We will not be seeing Alvin Greenidge this evening.

Chefette is Barbados’ homegrown “broasted” chicken chain. Locals consider it superior to KFC, which has failed to penetrate the island.

It is dinner time and it seems a reasonable bet that Murray will be happy to eat at one of their purple and gold-liveried restaurants throughout the capital. I can’t leave him at the bar in his current condition.

“What would you like, Dave?”

He looks at me like I’ve flushed his stash down the toilet.

“David!” he grunts, suddenly hostile to the abridged version of his name.

In the hire car, I suggest driving him back to Station Hill but he doesn’t want to go home. There’s fellow rebel Emmerson Trotman’s bar in St Lawrence Gap, but that holds no appeal, either.

We drive up and down Highway Seven, avoiding effluent spewing from manholes — the south coast was experiencing a huge sewage problem at the time — and tolerating each other’s company.

Eventually, he convinces me to let him out near the gaudy entrance to St Lawrence Gap. It is 9pm. Despite fears for his safety, I stick B$50 in his hand and wish him well.

He has played the game. Another foreign media representative seen off.

One last reprimand for calling him “Dave” again, and he shuffles into the night.

West Indies rebels to SA in 1983: Lawrence Rowe (c), Hartley Alleyne, Faoud Bacchus, Sylvester Clarke, Colin Croft, Alvin Greenidge, Bernard Julien, Alvin Kallicharran, Collis King, Monte Lynch, Everton Mattis, Ezra Moseley, David Murray, Derick Parry, Franklyn Stephenson, Emmerson Trotman, Albert Padmore (player/manager).

The Unforgiven: Mercenaries Or Missionaries? — by Ashley Gray.

Published by Pitch. Available from amazon.com.au and good booksellers.