Groundbreaking technology set to transform concussions in sport

When Australian boxing’s Olympic gold medal hopeful Justis Huni found himself out of sorts with a concussion after a ‘play fight’, he turned to new technology to get himself back on his feet.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

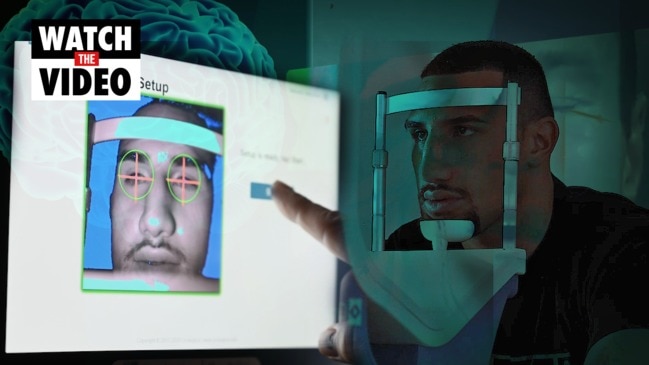

It’s the revolutionary $150,000 machine that could transform how sports diagnose concussion, and has already helped Australian boxing’s Olympic gold medal hopeful Justis Huni return from a dangerous street fight injury.

The Eye Box was developed in New York, is being used by NFL clubs, and has been brought to Australia by former aerobics champion Sue Stanley, who wants all codes using the world-first technology.

Unlike other eye scanners that simply track movement, the Eye Box can the ability to collect data from 200 different points in the retina to give a detailed insight into response times while watching short videos.

Kayo is your ticket to the best sport streaming Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Try 14-Days Free Now >

It correlates the information before giving a score between 0-20, with anything above 10 considered to be concussion.

Australian heavyweight champion Huni suffered a concussion just before Christmas last year when a play fight with a friend turned nasty.

“We were mucking around, and then it started to get serious, we started to wrestle and I got thrown into the ground, and that’s when I smacked my head on the ground,” Huni told News Corp.

“I got turned sideways and I hit my head on the concrete pretty hard.

“I didn’t tell anyone, things happen, I didn’t think anything of it. Two weeks later I had my first spar back and I got dropped.

“And I was sparring a cruiserweight. He caught me clean, it was a beautiful shot.

“But my coaches said they were worried because I’ve been hit from bigger guys with big shots.

“Then I went to [Olympics] camp, I was training at the AIS and I was getting bad headaches, migraines.

“I felt dark, like everything was dim and foggy. I still sparred at the AIS three days after I got dropped in sparring. I sparred but I just didn’t feel like myself. That’s when my other coach Mark Wilson was concerned, because he could tell I was slow, my reactions were slow. So that’s when I had to go to the doctor.”

Asked if he’d suffered any concussions, Huni recalled the street fight incident prior to his sparring blow.

It was then that his management team decided to use the Eye Box to determine how severe Huni’s condition was.

“My first score was over 10,” Huni said.

“And then I kept doing and I went down below. I don’t know if it was because I was focussing more because I wanted to be under it, but that’s when we knew I was concussed.”

Huni had planned to return to the ring in February, however that was put on hold until last weekend (April 10) when the Eye Box showed he had completely recovered.

“The thing that really excites me about the Eye Box is that it will save lives,” Stanley said.

“We can’t change the past. We can only draw a line in the sand and say we can now save the future.

“The Eye Box has got a massive potential because it is the world’s first FDA (the US Government’s Food and Drug Authority) approved non-baseline detection of concussion.

“And what it’s going to do is actually going to give informed information to the doctor, to the trainer, to the manager of the athlete of what the brain is doing.

“And if they’ve had a large knock, then how do you get them back to return to play? Because this is the interesting part, the sub concussion. We all know concussion, we all know that we have to take a break, but when does the actual brain settle down and go back to normality?

“And that’s something that we can’t detect and that’s something that Eye Box can detect. It actually gives you a score.

“We’ve actually proven this, we’ve seen this in New Zealand with some of the boxers when they have been knocked down, that they are concussed and they’ve had a high score.

“And then we’ve been able to monitor them daily as they come down and the score has come down.”

Another eye scanning machine, the Eye Guide, has also been introduced in Australia and is being used by Sydney private school St Joseph’s to monitor concussion in their rugby players.

Sport’s pandemic: Concussion what smoking was to lung cancer

This is sport’s pandemic. What smoking was to lung cancer in the 1950s.

That is the verdict of leading medical and legal minds delving into concussion and CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) as football codes scramble to deal with an overload of head injuries and multimillion-dollar lawsuits.

Sports are rapidly changing rules and penalties for contact to the head, insurers are reassessing whether they will cover concussions in their new policies, and alarming research has uncovered irrefutable links between head injuries and depression, anxiety, substance abuse, violence and suicides.

Just last week, Sydney Roosters NRL player Jake Friend retired due to repeated concussions, former US Olympic bobsledder Pavle Jovanovic was found to have CTE after hanging himself in May 2020 – the first athlete in a sliding sport found to have the brain disease – and the family of former NFL player Phillip Adams claimed he’d been “messed up” from football injuries after killing five people and himself in South Carolina.

“In medical sporting terms, this is becoming a pandemic,” said top lawyer Greg Griffin, who is leading a lawsuit against the AFL on behalf of the family of Shane Tuck, who took his own life in July 2020, aged just 38, and was later found to have the most severe case of CTE seen by Sydney’s Brain Bank.

“I don’t think we should let the sporting codes, the AFL, NRL and ARU (Rugby Australia), off the hook in terms of using their much greater resources than all of us have, to actually get the truth out there,” Griffin said.

“They’re in a chronic state of denial, and it’s as if they have to justify their conduct for the last 25 years, which is unjustifiable.

“What we’ve got is the AFL, which lives in fear of being exposed, for the manner in which – like the tobacco industry saying ‘You don’t get cancer from smoking cigarettes’.

“Thirty years later and countless deaths later, that’s all shown to be a lie.

“It’s disturbing the number of younger players, who are between 23 and 28, who are showing the early signs of damage and brain injuries.”

Leading Sydney neurologist Dr Rowena Mobbs is helping a host of retired athletes deal with major brain trauma, and is frustrated by the lack of willingness by Australia’s football codes to wholeheartedly engage with medical experts on this issue.

“We don’t know how big this problem is,” Dr Mobbs said.

“There’s this group of patients who have the sorts of trouble that replicate what we’ve seen in the US with American football, why wouldn’t we look more closely and delve into that, and not say ‘There’s no issue’ or ‘We won’t know for 40 years’?

“That’s not good enough for me when I’ve got patients rolling through the door, one or two a day.

“It’s been called a potential epidemic in the literature already, we have to do this work right now.

“The youngest person I’ve got concern about right now is 29.

“Why can’t sports grab this positive opportunity, for player brain health from kids right through. Is this not a golden PR opportunity?”

Dr Reider Lystad, a research fellow at Macquarie University and expert in head injury), delivered a sombre warning for athletes.

“I think the major concern is the risk of dying from neurodegenerative diseases,” Dr Lystad said.

“I’m not talking about CTE because we have a little bit of an issue diagnosing that clinically at this stage, but other degenerative diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. The data seems to suggest that the risk of dying from those newer degenerative diseases is about three to four times higher in former professional football players.

“That’s a major concern, especially considering that generally these football players are healthier than the general population, they have less cardiovascular disease, less cancer, but still, three to four times higher risk of dying from degenerative diseases.”

Former Wallaby Dean Mumm suffered two major concussions and many sub-concussive hits throughout his career, and revealed there is now a new anxiety among recently retired footballers.

“There’s an anxiety among professional ex-athletes, actually I won’t even say professional, ex-athletes or people that have been involved with a sport that has had repetitive head trauma,” Mumm said.

“Because if you sit there and you forget someone’s name, are you experiencing cognitive decline? Who knows, but that anxiety builds up, it’s a little bit scary.”