Welcome to the jumble: Boxing star Harry Garside’s dream in tatters

Aussie boxer Harry Garside’s Jungle Book reads like a litany of missed opportunities as he wastes time and money invested in him, writes PAUL KENT.

Boxing/MMA

Don't miss out on the headlines from Boxing/MMA. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Harry Garside was sitting back in the African jungle just recently, revealing how tough life is for your average athlete, celebrity, activist.

Everybody wanted to make money off him, he was saying, as he was allowing Channel 10 to make money off him.

“I hated turning professional, just people around me who wanted me because I was a potential cash cow,” he was saying to AFL player Adam Cooney.

“They didn’t want my best interests.

“It’s so dirty and I really didn’t like it.

“I hate knowing there’s people around me who didn’t particularly care about my wellbeing, they cared about the 10 per cent. It was really frustrating.”

It was a sad moment, but perhaps saddest of all, Garside doesn’t really know what he wants anymore.

Before he went into the jungle he said he would use the time in there to weigh up his future. Stay a pro, return to the amateurs, or leave the sport and raise kids.

“To be completely honest, I’m actually hoping this experience gives me the answers to all my questions,” he said.

![]Harry Garside doesn’t really know what he wants anymore. Picture: Getty Images](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/101f863b7ed70794ce0028d7fa90b662?width=650)

“I feel like I’m at a bit of a crossroads. The options are: professional boxing and make money (to) set my family up for life. Amateur boxing, make no money but honour my heart, my country, my pride. Or walk away from boxing.”

That was last month.

Last year Garside was going in the opposite direction, telling SEN Radio: “I want to try my best to be the best Australian boxer that’s ever been produced.”

Back then he was a marketer’s dream.

It was not just noble ambition, but a dream sprinkled broad enough to make the wider Australian sporting public believe this kid really might be different from anything we had ever seen.

The magic was that the line would resonate far and wide, through casual sports fans where all the dollars are, and far wider than the fight mob, who could see Garside for what he was.

Garside was finding that broader audience in Africa on prime-time television.

“I turned professional and I didn’t really know much about the professional game before I went into it, but I found myself hating boxing and I never once chased money,’’ he said, a camera nearby trained on him.

While that quote in particular caused mild amusement among his team, predominantly it sparked frustration.

Recently, Garside was found to be negotiating a worldwide sponsorship with a whiskey company without the knowledge of the man who had negotiated him a national deal with the same company.

He had proposed it but heard nothing back from Garside, who later informed him he pulled out of the international deal, citing “personal reasons”.

At least from the outside, it looked like he was chasing money. His promoter No Limit paid him a hefty sign-on bonus and has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars building his brand, trying to marry his profile with his talents, yet now the company’s owners, George and Matt Rose, couldn’t afford a Chinese meal with what they have made off him.

To make it into the jungle Garside, who hasn’t fought since last May, pulled out of a fight No Limit had booked for this month in Melbourne, after pulling out of another fight last September.

Again, it was likely going to cost the Rose brothers more money than they would make. All fight promotions carry an element of risk and for this one, Garside was going to headline a pay-per-view card at Margaret Court Arena against Brisbane’s Miles Zalewski, be paid $100,000, and have his old trainer in the corner while headlining a big fight in his hometown.

The fight was going to be a tough sell, as a pay-per-view, given Garside does not have a crowd-pleasing style and Zalewski is virtually unknown, but it was part of the investment strategy.

They had faith.

Instead Harry wanted to go into the jungle.

No Limit is now waiting until he leaves the jungle to talk about his next move.

Garside has told them he will be malnourished when he comes out so he will go to Saudi Arabia for a training camp with his Olympic coach and might also have a few amateur bouts.

It is increasingly looking like Garside wants to return to the amateurs. He has half a mind on France 2024, apparently.

His manager Peter Mitrevski Jr hasn’t spoken to him since January when Garside knocked back the Zalewski fight and said he was going on the TV show.

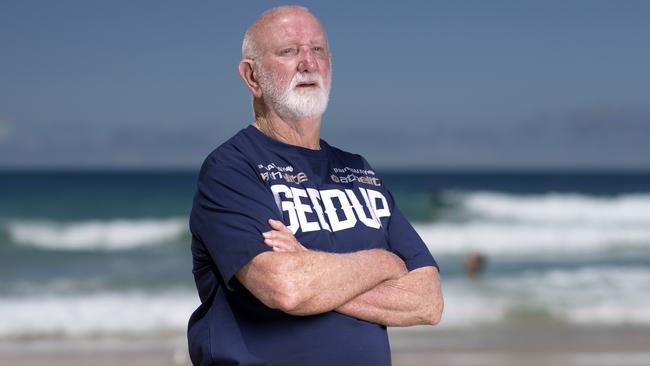

That was the end for Johnny Lewis, who realised right there Garside didn’t want to be a fighter.

Any fighter with ambition to be the best there ever was had to fight often, at least early in his career, to hone the skills.

Then Garside began resisting all efforts to shift him to a more professional style.

Lewis identified early that Garside was fading in fights.

In all but his first, a first-round stoppage, he fatigued. He never looked comfortable in his next two fights as a pro which went 10 rounds and then seven, respectively.

This kid needs something, he realised. He was up on his toes, in true amateur style, fatigued and moving to conserve energy, but he didn’t have enough venom in his punches to stop his opponents walking forward.

Once he hit the world rankings, it would be like going to war with water pistols. The tanks would roll straight through.

So Lewis delved into that history that takes him all the way back to the old Sydney Stadium days, watching men fight for a living when men used to fight for a living, and began working on teaching Garside to punch to the body.

Without a knockout punch, a good body punch would discourage his rivals from walking forward.

“It wasn’t going to win him the fight but it was going to help him not lose it,” Lewis said.

In those periods where Garside was getting hurt underneath, Lewis figured, at least he could go with them.

Finally one day, frustrated and unable to get it right, Garside walked over to assistant trainer Jayson Laing and his manager Mitrevski.

“He’s trying to turn me into Jeff Fenech,” he told them.

The shifting narrative, once again, irritated the trainer.

“I’ll tell you something, mate,” Lewis said to Garside.

“That’s something you can’t do.

“You haven’t got a skerrick of Jeff Fenech in your repertoire.”

In the end he realised he could do everything for him except make him fight, and so he quit.

And now a lot of people who invested a lot of money wait and wonder.

PROOF MAROONS’ ORIGIN ATTITUDE IS DIFFERENT

Nothing provokes a shot of anger from former NSW players like the suggestion, and one made repeatedly, too, that Queenslanders are more passionate about Origin than them.

But the Maroons not only say it, they prove it.

They back it with action.

Billy Slater’s statement during the week that Corey Horsburgh is being watched with Origin in mind surprised many but not those who understand Queensland.

“That stuff there, the kick-chase, the cover tackles, all that effort stuff, that’s a habit in your game,” Slater said after Horsburgh’s game against Brisbane last week.

“When you play Origin, you’re tired, you fall back on the habits in your game … that’s stuff we take notice of.”

No doubt there have been passionate NSW players over the history of Origin, the kind of players where winning and the blue jersey means as much to them as it does to very best of Queensland.

But when NSW teams get picked like last year, with Jake Trbojevic overlooked for the opening game when he would be first picked for Queensland given what he brings to the game, and to his team, it underlines the narrative that NSW is a talent first, character second type of team.

The Blues first fell for this in the early days of Origin and, except for a few brief periods of respite, are falling for it all over again now.