Nate Jawai’s last ride: Bamaga to the NBA, NBL and the Australian basketball great’s impact on hoops

As Nate Jawai gears up for a final farewell from basketball, he opens up on his rise from Bamaga to the NBA, the health scare which almost ended it all, the Patty Mills NBL return rumours, and what’s next.

Basketball

Don't miss out on the headlines from Basketball. Followed categories will be added to My News.

As he gears up for a final farewell to basketball, the first Indigenous Australian to make it to the NBA Nate Jawai has opened up on his rise from an isolated town in far north Queensland to the big time — and the unique challenges and triumphs he’s faced along the way.

A distant cousin of Patty Mills, Jawai addressed the speculation about the Boomers great’s potential return to the NBL, ahead of Wednesday’s Indigenous Basketball Australia All Stars showcase.

BAMAGA TO THE BIG TIME

Jawai calls Bamaga, an Indigenous town of around 1100 about 40km from the northern tip of Cape York, home.

So, once he found basketball as a teen, whether it was the AIS, Midland College in Texas or the NBL, the learning, culture and language curve were always steep.

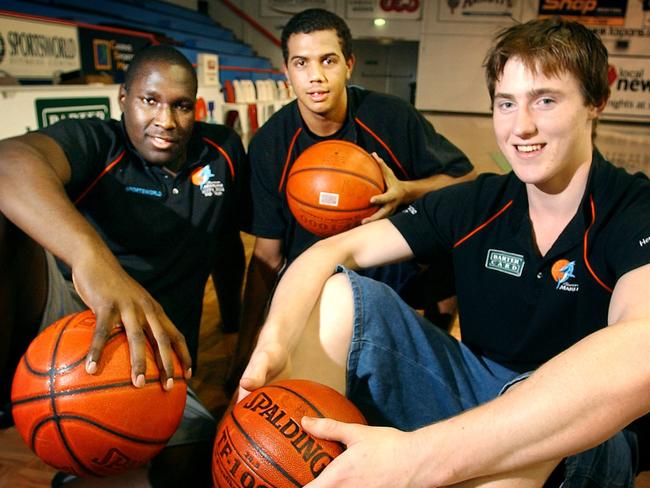

Not that it stopped the shy 209cm, 130kg giant from performing — he won the 2007-08 NBL Rookie of the Year award in his first season in Cairns with veteran-level production of 17.3 points and 9.4 rebounds.

That, along with his marvellous size, put Jawai on the radars of NBA teams and soon he was on the plane to the US for workouts.

“I’ve never been a person that likes the attention and everything happened for me so quickly.

“I didn’t even start playing basketball until I was 17 and then everything just went haywire for me.

“I didn’t have time to grow up, to be honest with you, it was tough.”

At the time, Bamaga was a community of less than 800 people, its inhabitants speaking a variety of languages, including Kalaw Kawaw Ya, Brokan (Torres Strait Creole) and English.

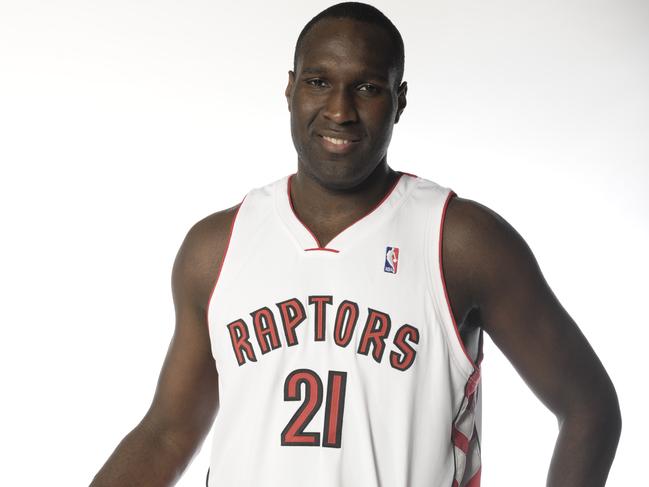

All of a sudden, he’s a Toronto Raptor, in the bright lights of the NBA, in a city of four million people.

“I go over to the states, and it’s a whole different ball game and everything’s just an eye opener,” he said.

“It’s hard to take a kid out of a community like that and I think that’s what I struggled with the most, being away from home and family.

“Family means everything for me, my mom and dad, my cousins, and I’m away, and it’s all foreign to me.

“I didn’t speak English that well, I didn’t know how to use some technology, I didn’t know the culture. I didn’t even know the game very well. It really was a whole different world that I had to try and adjust to.

“You’d have these confident European players that didn’t speak English well but they didn’t care. That wasn’t the same nature as me.

“I was more embarrassed. I wanted to be able to communicate and I didn’t want to be a fool.

“So for me to get out of that comfort zone was daunting.

“But it turned me out to be who I am.”

COMMUNITY KID’S ‘DIFFERENT’ DRAFT EXPERIENCE

Up to five Australian young guns could be crossing their fingers and toes their name is heard at June 26’s NBA Draft.

Jawai says his draft night was a unique one.

He was in New York, but refused to attend the draft.

Instead he, agent Daniel Moldovan and then-Cairns assistant coach Aaron Fearne — one of Jawai’s greatest career influences — watched the broadcast from ESPN Zone in New York.

“I remember Daniel was trying to get me in a suit and trying to get me to go to the draft at Madison Square Garden but I was just like, ‘no, I don’t want to go, I’m fine’,” Jawai recalls.

“I’m a community kid and I was 21 years old.”

Watching on the screens as names were called, one-by-one, Moldovan was alerted the Indiana Pacers planned to draft Jawai in the second round.

“He was sitting with four or five phones in front of him and, toward the end of the first round, those phones were going off,” Jawai said.

But Jawai would never hear his name called.

“We were just sitting around the table having dinner and watching the draft and there was a commercial break,” he said.

“When it came back from the break, I saw my name on the screen — I got drafted while they were on an ad break.

“I said to Daniel ‘Oh, I just got drafted, No.41’.

“I don’t think I even reacted. I think I was just more like, ‘oh is my life changed now?’

Jawai took a walk around NYC, went back to his hotel and then called mum and dad.

“I didn’t really like the tension so I was like, ‘yep, happy, I got drafted, let’s go’,” he said.

“It was a bit different but I wouldn’t change it.”

SIMPLE ADVICE FOR AUSSIE DRAFT HOPEFULS

For the likes of Alex Toohey, Rocco Zikarsky, Lachie Olbrich, Ben Henshall and Tyrese Proctor, who are all still in the draft as of Sunday, Jawai’s message is simple.

“Enjoy it.”

“I remember I was over there for a month and a bit before the draft and I had 13 workouts scheduled but I got injured halfway through, tore my hip flexor and my workouts got cut in half.

“I thought, that’s it, I’m probably not going to get drafted now, I was going back to the Taipans.

“I didn’t really take it into account at the time but, when I look back, the draft is probably one of the most fun things I ever did in my career.

“I’ve made some friends who were in the same draft class, played against them, played with them either in the NBA or in Europe and we’re still friends today.

“I didn’t know how big the basketball world was.

“You never know what’s in front of you so don’t take it for granted and enjoy the process because you only get to do it one time.”

THE HEALTH SCARE THAT ALMOST ENDED A CAREER BEFORE IT BEGAN

When doctor’s detected the heart that powered Jawai’s massive frame was enlarged and said he had to stop playing basketball while they investigated its cause, he feared the worst.

And he had to face it virtually alone.

“I keep coming back to being from a small town but I was 21-22, didn’t have mum and dad there, I had Daniel and Fearney on the phone a lot, and that’s it.

“I was going to appointments by myself. So many heart scans and MRIs and dye going through your veins.

“I wasn’t allowed to get my heart rate over 100 so I couldn’t even run, let alone play.

“My career just stopped.”

Even if he survived the abnormality, what would it mean for his basketball?

“The doctors said I had to stop everything. I couldn’t play for nearly the whole season,” he said.

“I was new to the game, It was only my fifth or sixth year playing basketball ever.

“I knew I could play but I was raw. I didn’t know the NBA game well and I wasn’t able to do anything, so I couldn’t really learn anything and get better.”

Finally cleared to play, Jawai would make his NBA debut in January 2009 — nearly seven months after he was drafted by the Pacers and traded to the Raptors.

By July, he was experiencing the business side of the NBA when he was sent from Toronto to Dallas — then, in October, the Mavericks shipped him to Minnesota.

“I had to move house and move countries to Dallas and then a couple months later do it all again from Dallas to Minnesota,” he said.

“I’d hardly even trained or played properly yet and I had to keep packing everything up, finding a new place to live, it was tough.”

EURO-TRIP PROVIDES RENEWED SPARK

Jawai opted to leave the NBA at the end of his two-year deal and found greener pastures in Europe, first with Serbian powerhouse Partizan, then in Russia, Turkey, Andorra, France and, of course, Spain, where spent a season with giant Barcelona.

“Going to Europe was probably one of, if not the best, basketball decision I made,” Jawai, who won MVPs and a swag of titles during his years in Europe, said.

“I just wanted to play.

“I got to Serbia and I started to enjoy my basketball again.

“I’m a cultural person, I’m Torres Strait Islander, Indigenous.

“As soon as I got to Belgrade, with the history in that city, I was like ‘yes, I’m not at home, but I’m kind of at home’.

“I could relate to the culture and soak it up, it was easier for me.”

WHY THE SHAQ COMPARISON’S GRATED

Jawai’s a gentle giant, but his sheer size and imposing physique earned early comparisons to NBA superstar Shaquille O’Neal.

But he audibly cringes when the nickname Baby Shaq or Outback Shaq is mentioned.

“Baby Shaq? He was an icon, I was nothing like Shaq,” he said.

“Outback Shaq? I didn’t like that nickname.

“I was the only dark Australian in the system at the time, It was weird to me.

“I didn’t know how to take it. Are they singling me out?

“I didn’t like it then and people still call me it today and I still don’t like it.

“I just brush it off and not say anything when people say it.”

A good public note to anyone next time they think about using those nicknames for Nate.

PATTY SNAKE? NO IDEA, BUT NATE RECKONS IT’D BE GREAT

The NBL rumour mill went into overdrive over the past couple of weeks, amid suggestions Mills might have an interest in purchasing and/or returning to play for Cairns Taipans.

Jawai is quick to make the point that he hasn’t spoken to Mills about those rumours and has no insight into his plans for the future.

While Code Sports understands Mills to Cairns won’t happen, at least not this season, Jawai says he would love to see the Tokyo Olympic bronze medallist back in the NBL one day.

“I’ve had like 10 journalists ask me what Patty’s doing but I honestly don’t know anything about it,” Jawai, who spent seven of his eight NBL seasons with the Taipans, said.

“But it would be awesome if he were to take over ownership of the Cairns Taipans. That would be big time.

“He has done so much for our people. Cairns deserves a private owner with the direction the NBL has moved in so they can compete with the other teams.

“I’ve always wanted what’s best for Bala and, if he does do it, I think it’s great, but I still think he has a lot of basketball left in him.”

Despite talk of an NBL homecoming, it appears more likely Mills is set to stay in the US for at least another year to focus on the birth of his first child with wife Alyssa, due in August.

Los Angeles Clippers officials were in Australia recently and a source said there remained an interest in bringing Mills back for what would be his 17th NBA campaign.

Mills could still invest or play for an NBL team in the future.

Currently a free agent, sources said Mills was hopeful of re-signing with the Clippers.

At 36, he is no longer the starting-five force of yesteryear, but his championship-winning experience provides any NBA franchise with a veteran locker room presence.

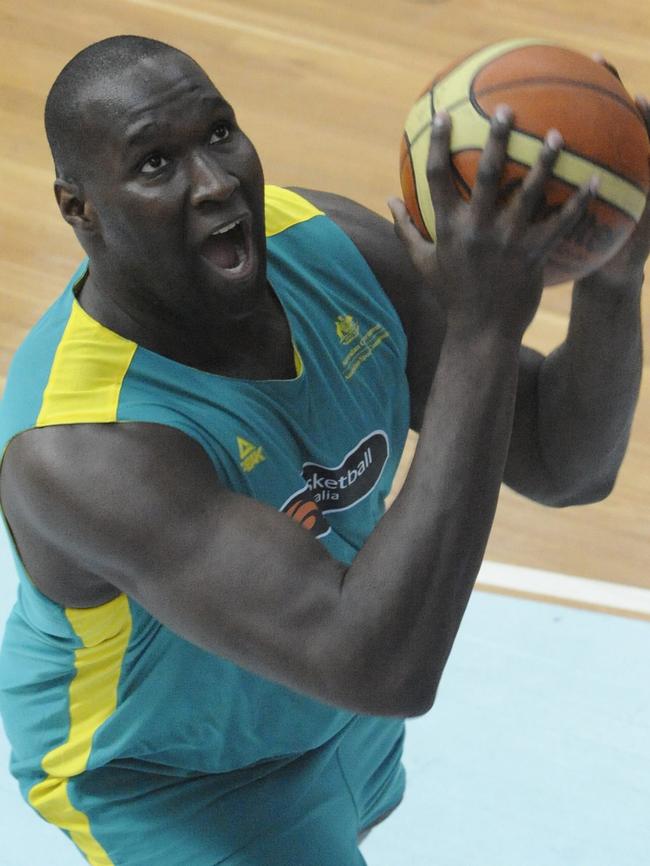

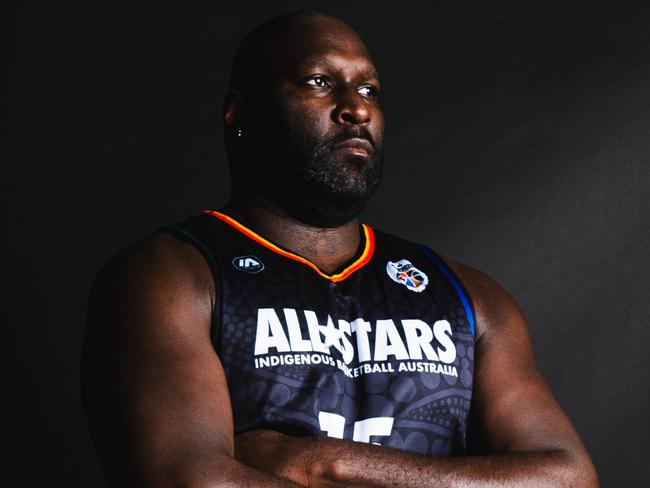

TRADITION BUILDS FOR NEXT GEN

The IBA All Stars, founded by Indigenous NBA star Patty, wife Alyssa and parents Uncle Benny and Aunty Yvonne, now in its second year, has fast become a significant event on the Australian sporting calendar.

The games showcase the finest male and female basketball talent from First Nations backgrounds, many of whom are playing in the NBL and WNBL.

But it’s more than that, Jawai says.

“Pat’s done a great job organising all this for us to have but, If you really think about it, back in the day, it was pretty much just Pat and I in the professional basketball realm,” he said.

“We had (Aussie Indigenous basketball pioneers) Uncle Danny (Morseau) and Michael Ah Matt before us who paved the way, but we know now there are more and more Indigenous kids coming through wanting to play basketball and be involved.

“And so it’s important for people like me and Patty and (former Illawarra Hawk) Tyson Demos who have been through the ups and downs and experienced the racism and the successes to be a support network for all the younger kids coming through.

“We can talk about the negatives and the racism that all of us have been through but this is bigger than that — it’s the connectivity to have all of us together, sharing this game that’s really important to us and share each others’ story and show what people from our community are capable of.

“It’s a family environment, getting back to your culture and your identity, to share who you are and learn about each other.

“I was a shy kid and basketball has opened up so many doors for me because of the connections and it’s kind of the same thing that this game can do for the younger Indigenous players involved.”

A NEW BEGINNING, FOUR DECADES IN THE MAKING

Life’s come full circle for Jawai.

Basketball is done — or will be after Wednesday night — and he’s focused on the launch of his new not-for-profit charity Thoegayn Zugub.

It’s an Indigenous language name, linked to his clan, and, through the foundation, he wants to reach as many First Nations children and youth as possible to ensure they have a support and role model when navigating the same challenges he was forced to face alone.

“It’s time for me to get back, and I think it’s important to go back into grassroots, where I started, and kind of spread the message of healthy living share my journey and where I came from,” he said.

Originally published as Nate Jawai’s last ride: Bamaga to the NBA, NBL and the Australian basketball great’s impact on hoops