Chris Fagan has a chance to etch his name into the history books on Saturday. But, as MARK ROBINSON, finds out, his story is already worthy of acclamation. And it’s one that starts in a mining town in western Tasmania.

Kevin Sheedy reckons the stories make football.

It’s why the tale of Chris Fagan resonates so much.

At 63, Fagan will become the oldest premiership coach in VFL/AFL history if the Brisbane Lions win on Saturday and he would be the first coach to achieve it without having played league footy.

But that ain’t the story. That’s the end bit. It’s the other bits that enrich the Fagan journey.

As a boy – and knee-high to a grasshopper as they’d say in the old days – Fagan grew up in Queenstown, a mining town in western Tasmania.

NOTE: THIS STORY WAS WRITTEN BEFORE THE 2024 GRAND FINAL

Comparable to the Texan town of Odessa in Friday Night Lights, which breathed oil and football, Queenstown breathed mines and Australian rules.

Teams have folded and merged in the Western Tasmanian Football Association, but clubs that left their mark included Lyell-Gormanston, Queenstown, Strahan, Zeehan, City Magpies, Mines United, Railway, Tullah, Rosebery and Smelters Robins.

Fagan’s dad and uncle played for Smelters and his dad also was captain-coach of Gormanston. Young Chris played for Lyell-Gormanston after the amalgamation of the two teams and, aged 15, he played in the senior premiership.

A frontier town then and now, Queenstown is famous for originally being a gold-mining town settled in 1881 and, in a sporting sense, is famous for its gravel football ground and one-time barren hills.

In 1954, famed writer Geoffrey Blainey pulled back the town’s covers when he penned The Peaks of Lyell, a history of the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company, and more recently, in 2021, a book titled Gravel & Mud, compiled and edited by John Carswell, Tony Newport and Chris Carswell, detailed the history of football in the mountains of western Tasmania.

Today, about 1900 people call it home – and mining remains its major employer – and Fagan is the town’s second-most famous sporting son.

The first, of course, is Ian Stewart, the triple Brownlow medallist.

That makes Queenstown, a speck on the map about four hours’ drive northwest of Hobart, just about as far flung as football can be.

Sheedy has more yarns than Moses and he says the Fagan story is one of the most unique and most inspiring.

“He’s the man from nowhere,’’ Sheedy said.

He never played AFL at the highest level, or VFA, he was coached by Paul Sproule – the most underrated player I played with at Richmond – and now he’s a highly successful coach at AFL (level). Football finds people from every corner of Australia.

“Two other great stories roll with Fagan. I think Isaac Heeney is from Cardiff, not from over in the British Isles, but Cardiff in Newcastle, and the other great story is Lachie Neale, he’s from Kybybolite, do you know where that is?’’

Kybybolite is on the Victorian border, 300km southeast of Adelaide and 19km from Naracoorte. Population about 100.

“This is what this great game throws at you,’’ Sheedy said. “Heeney, Neale and Fagan. It’s unbelievable. Heeney has willed himself to make it, and so has the dual Brownlow medallist, and the coach is from nowhere, and he picks up the team from last and says, ‘I think I will have to go at this’. Fagan is a great name for a leprechaun, it sounds so Irish doesn’t it?

“If you want to write a great script for a story, this is one of the best.’’

THE LONG JOURNEY FROM THE MOUNTAINS

Geoff Poulter and Robert Shaw are proud Tasmanians. One was an esteemed footy journalist, the other a former AFL player and coach, and both have infectious eccentricities that make them wonderful storytellers.

Poulter is 76 and remembers being a young lad in Kingston State School and poring over the Hobart Mercury, lost in the ocean of football results from around the state.

Being a city kid, the Western Tasmanian Football Association was a kind of mythical world in the mountains.

“It was something out of a western movie, a long way from civilisation, a bit like Broken Hill,’’ Poulter said.

“And the most famous family on the west coast was the Fagans. I can still remember looking at the results – Fagans would be in the best players, Fagans would be in the goalkickers.

“Like the Selwoods and the Danihers, just a lot of representations from the Fagan family.’’

The Fagans who Poulter recalled were Austin and Gerald, the father and uncle of Chris. Austin was a legendary player and coach and Poulter said Chris was, incidentally, a “clever” player, a “poor-man’s Lachie Neale’’.

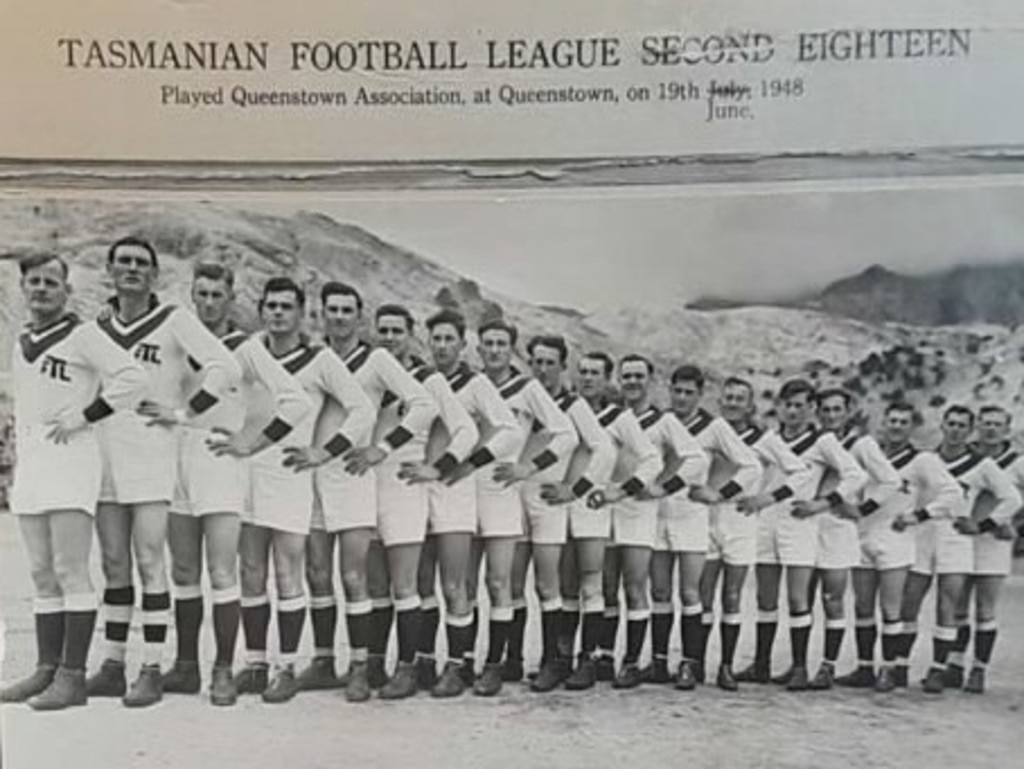

Shaw has been to Queenstown half a dozen times. His old man, Bert, played there in 1948 when a representative Tasmania Football League team (the south) played a game against the WTFA (the west).

In February this year, Shaw went back to the ground and stood on the exact spot where his father stood in the team photograph in ’48. Did we say he was eccentric?

Asked to describe the ground, Shaw said: “It’s in the valley. You drive over the mountains, wind down into Queenstown, and as you come into town it’s there on your right. It’s got a rivulet around it, there’s old sheds, a grandstand, a gravel ground.

“My dad played there in ’48. It’s still a four-drive from Hobart, so can you imagine playing there in the 1950s and ’60s, travelling on the roads in the team buses. It’s amazing.’’

He says Fagan exudes passion.

“And he’s taken the long journey from the mountains,” Shaw said. “He has passion for the game, he loves the people of football, he loves the engagement and it came through even when he was playing in Tasmania.

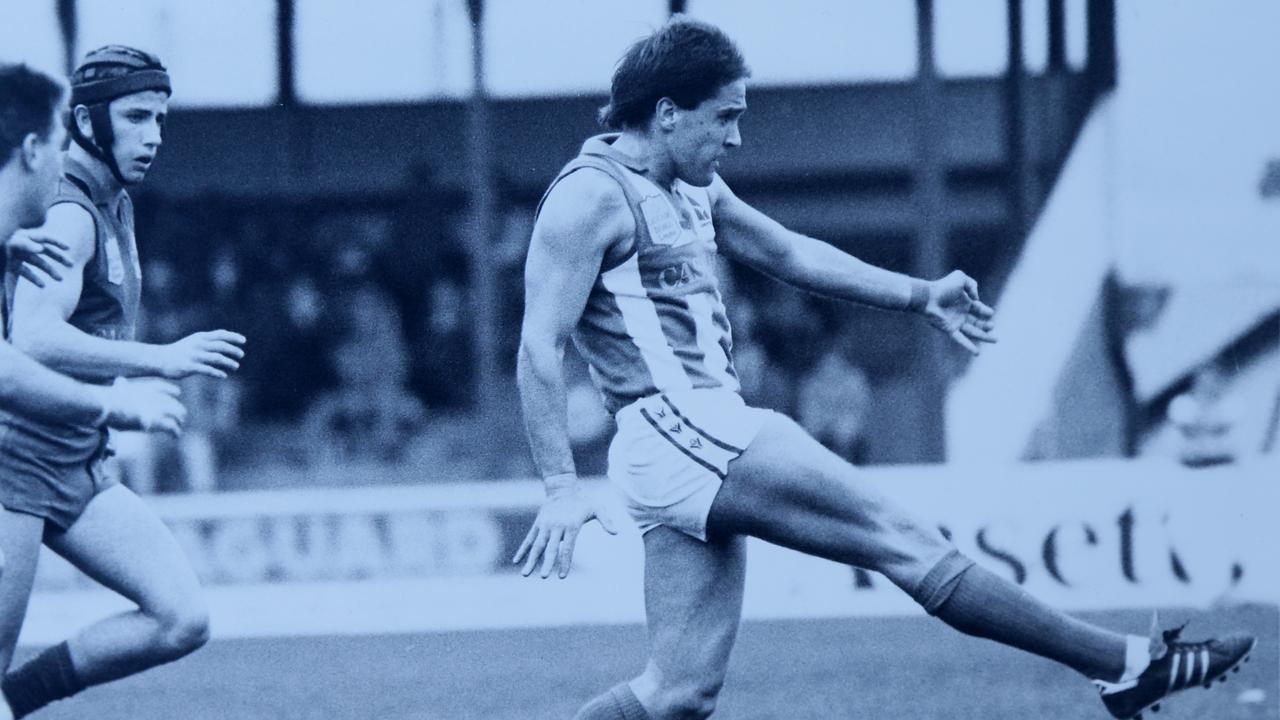

“He just loved playing the game. He was enthusiastic, he was a good player, a professional preparer in the mid-1980s, which meant he was well before his time, and had a huge workrate.

“Even looking back now, and I played against him – I was captain-coach of Clarence and he was first rover for Sandy Bay – if you were asked who would’ve made a good coach back in your day, you would’ve said Chris Fagan.’’

LIFE BEYOND QUEENSTOWN

Scott Wade was first rover and Fagan was second rover in Hobart’s 1980 premiership team, coached by Sproule.

Their dads – Austin and Michael – were teammates at Hobart in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and the boys arrived at the club as teenagers under the father-son rule.

“I spent a lot of time with Fages in those early days,” Wade said. “There was a bloke who played at Essendon, Mal Pascoe, who coached us, then Sprouley came along.

“I suspect Fages would talk about how much Paul Sproule had a big influence on him.”

Wade said Fagan would often whinge because, as second rover, he didn’t get enough time on the ball.

“Fages’ nickname in Tassie is Junior, because he was the junior rover to me,” Wade said.

“He doesn’t like that nickname.”

Fagan said he was given the nickname by a bloke called Peter Gray.

“He was an old guy and he called himself ‘The Master’, he called Wadey “The Apprentice’ and then I turned up and he called me Junior. And I got called Junior after that,’’ the Lions coach said.

Wade says Fagan’s attributes then are evident today.

“I’ve never seen a young bloke work so hard,’’ he said.

Customary to the day, winter was for football and summer for cricket. But not for Fagan.

“He took up athletics in the summer because he just wanted to get better at footy,’’ Wade said. “The blokes who played with and against Chris would say he got the very best out of himself. He was one of the players who never left anything in the tank.

He has utmost respect for work ethic, professionalism, and the super high standards that he set. I’m also good mates with his brother, Grant. I’m part of Clarence and Grant coached four flags there, and they are the same, they are just exceptional relationship-builders.

“That’s the Fagan clan. They are so professional and committed at what they do. They genuinely care about people.’’

The major influencers in Fagan’s life are family: Sproule, Neale Daniher, Alastair Clarkson, Leigh Matthews and, in the past five years, Phil Smyth, the basketball great who has become a leadership mentor at the Lions.

“Paul Sproule was a big influence. I watched the way he coached. He was one of those coaches who could teach you about the game as opposed to just a rah-rah coach. I found that beneficial,’’ Fagan said

But no one beats Dad.

“Dad was my best friend,’’ Fagan said of Austin, who died in 2019.

In the preface of Gravel & Mud, Fagan wrote: “When I was a young bloke, he (dad) also wrote a column on west coast football for the Advocate newspaper. I can still remember reading his handwritten drafts every week before he handed them in for publishing. He wrote with passion and intelligence about the game and people he cherished. He coached with the similar empathy and care for his players. He passed on to me a love of the game and a great interest in coaching. He was a role model to me in the way he lived his life, his competitive instinct, his generosity towards people and the way he cared for our family.”

Fagan attended St Joseph’s Primary School and Murray High School in Queenstown, and then Elizabeth College in Hobart to complete Year 11 and 12.

Asked to describe Queenstown, Fagan said: “It gets a bum rap, but that’s all I was used to. I thought it was a great place to grow up. It was a close community, a lot of sport was played so I loved that. I had good teachers at high school who encouraged me to maybe think beyond living in Queenstown when I finished high school. They kept saying to me, ‘You don’t have to stay here and work in the mine’, because there was a copper mine in town.’’

Told that Wade described Queenstown as the wild, wild west, Fagan smiled. “It’s more civilised than that … only just. It was a good place to grow up. I had great parents who sacrificed a lot for myself, my two brothers and sister. I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now if they hadn’t got us out of that town to be honest. Not that I speak badly about the town, I loved it, but there was life beyond Queenstown.’’

The family moved to Hobart after Fagan finished Year 10, in part so he didn’t have to board or live in a hostel to complete high school. Then it was off to university to study teaching.

Well-travelled after stints at Hobart, Sandy Bay, Devonport, North Hobart, the Tassie Mariners, Melbourne, Hawthorn and the Brisbane Lions, Fagan has a truckload of stories himself.

Two of them involve Sheedy.

“For some reason, Sheeds has always taken an interest in me,” Fagan said.

The first came when Fagan was 12 years old and Austin brought the family to Melbourne for Easter weekend. Mad Richmond supporters – they adored Royce Hart – they ventured to Moorabbin to watch the Tigers play the Saints. By chance, the family sat next to a Richmond director, who invited the boys into the rooms pre-match.

“We walked into the rooms and were introduced to Kev (Sheedy) and he took us around the rooms and he introduced me and my brother to all the Richmond players,’’ Fagan said.

“It was unbelievable for us, and Sheeds did that.

“When I look back, Sheeds was playing a game of footy that day, but he also took us around the rooms. Richmond won the game I remember.’’

Another memorable meeting took place when Fagan was the inaugural coach of the under-18 Tassie Mariners.

“I remember him asking me one day, who’s the toughest player playing in the TAC Cup and I said Dean Solomon,’’ Fagan said. “And he drafted him. I don’t think (it was) on the back of me saying that, because he probably asked that question of 10 TAC Cup coaches and they probably all said Dean Solomon, so Sheeds probably said I’ll get a tough bastard into the team.’’

Fagan has adopted the “tough bastard” philosophy as coach of the Lions. As he set about rebuilding a club that had won three, four and seven games in the three years before his appointment in 2017, and five games in each of his first two seasons, Fagan wanted talented players. He also asked the recruiters: Are they tough?

“I think my boys are tough this year,” he said.

He said the experience of last year’s grand final, which the Lions lost by four points to Collingwood, had his team less “buzzing” this week and wiser to the occasion.

“To live through it already is pretty handy,’’ Fagan said.

I noticed on Monday, there was a calm around the place. I felt last year everyone was buzzing, but on Monday the boys came in, did what they had to do, doing some media stuff, but there was no real carry-on.’’

Fagan also was calm in the aftermath of the preliminary final, which was different to his excitable on-field celebrations after the incredible comeback in the semi-final.

“Yeah, I was good, but I always feel like I’ve been out drinking beers all night a day after a game,’’ he said. “I didn’t have one drink, but you just get so much adrenaline game day and you don’t sleep much that night, and you feel pretty rat-shit the day after a game to be honest. I was in bed early Sunday night.’’

Grand final day is legacy day for coaches and if the Lions win, Fagan will be written into the history books. Yet his story is already worthy of acclamation.

Great friend Neale Daniher once said of him: “Finding Chris Fagan was the best recruiting decision I made in all my time at Melbourne.’’

He’s the man from nowhere who became somebody.

“Once a Tasmanian, always a Tasmanian’’ Wade said. “And Fages is a Tasmanian and we love him.’’

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

AFL Now: Awkward detail in Allen apology presser emerges

Eagle-eyed fans have spotted an awkward detail in Oscar Allen’s press conference where the Eagles co-captain admitted he was embarrassed and ashamed for meeting with Hawthorn.

‘Ashamed’: Star breaks silence on saga

West Coast Eagles captain Oscar Allen has spoken out for the first time after he was caught having a meeting with a rival coach.