It was a tragic accident that helped shape the lives of a teacher and a student in a small country town. Now, 15 years on, they catch up once more to speak about the unlikely path that’s led the teacher on a mission to rebuild the Brisbane Lions. KYLE POLLARD reports.

ON A WARMER than average April day in 2005, a small town PE teacher is getting ready to host a staff breakfast to mark the end of Easter Holidays.

It’s an event he holds every year. His yellow weatherboard cottage sits directly across the street from the school, perfectly placed for his fellow teachers to wander over and start getting ready the day before another hectic term.

He enjoys these days. Like any typical PE teacher he’s personable, good with a crowd, a disarming cheeky smile – a casual bloke that almost always wears shorts.

As he prepares to venture out to grab the morning’s newspapers, he gets a message on his phone.

Two of his former students - a brother and sister who had only recently gone to uni - are dead. Killed late the day before in a tragic car accident on a country road not far away.

It’s a message that’s been gradually snaking its way right throughout the community, right throughout the night. A message that shakes the entire town.

A message that shakes the teacher.

Like anyone in the same situation, he seeks guidance in an authoritative figure. He starts to call the school principal, but the familiar sound of the St Kilda theme song ringtone starts chiming outside his door.

The Saints-mad principal has already arrived. He’s been awake since 2am when he got the call, spending time with the families who were close to the kids. Their own family, somewhere out the back of Burke, unreachable while on a 4WD desert getaway.

“What do we do?” the PE teacher asks, as they both face a situation they’ve never been in before, and one they hope they’ll never be in again.

The message has a distinctly footy feel to it. We stick to the game plan. We do what we can to protect our students, protect our staff, protect our community.

For now, the PE teacher is to venture out to get the newspapers like he always would, to see if anything about the tragedy has been reported in the press.

It’s a short drive to the main street. Under two minutes. But it feels longer on this day. That clear April morning suddenly darker than anyone could have possibly imagined. As he pulls up outside the newsagency, he’s greeted by a front page emblazoned with photos of the crash. A wrecked Ford Falcon XR8, destroyed to the point it barely looks like a car anymore.

Then, from down the street, a group of four students appears, wandering, mentally lost, on the worst morning of their lives

They’re the best friends of the deceased.

The teacher doesn’t really know what to say. What can you say? On the worst morning of these kids’ young lives, nothing he could possibly impart could make this better. He’s lost for words.

But for one of the students, the mere presence of the man with the cheeky grin and the disarming personality is comforting in itself. A small light of guidance on a black day. Someone to follow. A leader.

It’s a moment that student remembers as clear as it were yesterday.

The teacher, for what it’s worth, is Paul Henriksen, now a development coach of the ever rising Brisbane Lions.

The student was me.

And we now sit under the Gabba grand stands to talk about that inherent leadership, and how a group of school teachers are guiding this young Lions squad to greatness.

SCHOOL’S IN FOR FOOTY

“YOU DO REFLECT on those sort of things,” Henriksen says when asked about the impact that tragic day had on him as a person and an educator.

“I was a teacher for 19 years but for 10 of those years I was Head of School so you have to look after those things that happen outside of the classroom.

“A lot of those experiences that 16, 17, 18-year-olds go through make you realise that there’s more to this job. You begin to tell quite quickly whether people are OK or not.”

On that day – when I lost two of my best friends – I wasn’t even close to OK. But that memory of seeing Mr Henriksen – or ‘Henry’ as we called him – on the street outside the Terang newsagency will live with me forever. It was a moment of clarity. That even though everything was a mess, the teachers were there to help us through it.

“The students never forget and we never forget the students,” Henriksen says, as we sit in the common room of the Brisbane Lions before the 2020 season was set to kick-off.

Behind us Chris Fagan is doing an interview with another journo, dual-premiership Cat Josh Hunt is kicking a footy to himself, and future captain Harris Andrews is making himself a drink.

It’s a long way from Terang.

A town of just 2000 people, with a high school of about 200 kids.

Just north of Terang is the tiny town of Noorat, and just north of Noorat is Kolora - a place that’s more of an idea than a town these days.

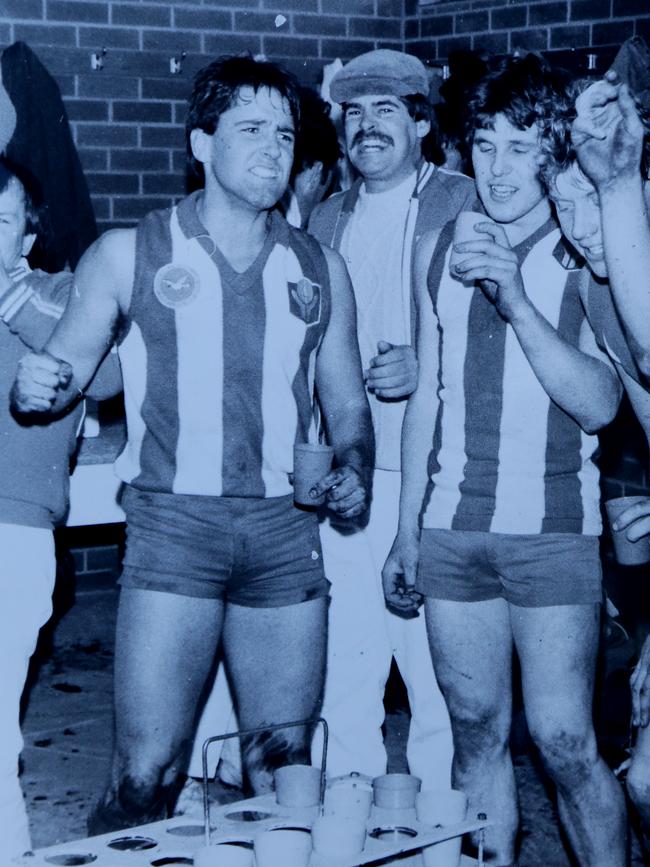

And it was at the Kolora Football Club that Henriksen started to make a name for himself as a footy player and coach.

“Yeah I played out there and then I got the call to do a bit of coaching,” Henriksen says.

“I coached the U18s my first year as a teacher so I started coaching and teaching at the same time.

“At the time it was just, ‘well you’re a teacher, you can coach the kids as well’, that was the philosophy to be honest. It wasn’t something I necessarily chased.”

He was one of several teachers of the small staff at Terang College who would spend their Tuesday nights, their Thursday nights and their Saturdays continuing to impart their knowledge when they had every right to be off the clock.

Over at the Noorat footy club – arch rivals of Kolora before their eventual merger – English teacher Adam Box would look after the junior Bombers.

In Terang, fellow PE teacher Adam Dowie had the responsibility of shaping the future of the young Bloods, a club rich in history and packed with eventual VFL and AFL stars.

Dowie would go on to coach the Terang-Mortlake seniors. Then Warrnambool. Then Koroit. And now North Warrnambool, winning five premierships along the way in the blue ribbon Hampden League.

“Yeah Dowie and I would spend a little bit of time between classes at school with our pads out,” Henriksen says.

“Just going over a few things, talking about a few strategies and drills and things like that.”

It was these staffroom chats that would help lead both men further down the paths of coaching. For Henriksen, a journey that would see him involved in interleague duties, before joining the elite Geelong Falcons program as an assistant, then being promoted to Vic Country U16 coach in 2012, and Vic Country U18 coach in 2014.

All the while still living in his cottage across the road from Terang College.

And then the Brisbane Lions called.

“With the Year 12s, we’d always talk about them getting out of their comfort zone when it came to leaving school,” Henriksen says.

Here I am still living in Terang, still living across from the school. How can I teach others to get out of their comfort zone when I’m firmly in it? Sometimes you’ve got to practice what you preach.

“It was a big decision. But it was good for me and for my growth, where you have to adapt like some of the players do when they’re drafted up here. To have that understanding of what it’s like to move and shift and bring a family up.”

It was an emotional farewell to a community that had given him so much, and a town that he had given so much to.

But he was joining a club that was on the brink of a revolution.

And it was a revolution being led by teachers.

FAILING TO SUCCEED

“I DON’T FEEL like I ever did quit teaching,” Lions coach Chris Fagan says, 26 years after he last set foot in an actual classroom.

“I think teaching and coaching are the same jobs, it’s just a different environment.

“You’re still doing the same things, trying to teach the boys how to play the game but build them up as people first and foremost. Help them through their highs and lows if they’re experiencing difficulties, help them if they’ve been successful and figuring out how to you handle that.

“So there’s all these life lessons.”

Fagan isn’t the first head coach with a teaching background, nor will he be the last. But his journey to the top of the Lions tree is distinct in the fact he never played the game at the highest level.

Born and raised in Queenstown on the west coast of Tasmania, it was the done thing for boys in the area to leave school and get an apprenticeship, to work with their hands and often do the jobs their dads had done before them.

But Fagan saw another path.

“I had a couple of teachers who were really influential on me and made me realise I didn’t necessarily have to do what the other guys were doing in Queenstown,” he says.

“What I enjoyed is how much they helped me and guided me and for that reason I thought, well, that’s a job I wouldn’t mind doing myself so that’s when I moved to Hobart.”

By the end of 1982, Fagan had his teaching degree, and scored a job in the suburbs of Hobart for five years, before a couple of years at Sheffield District High School, then five more at Dominic College.

All the while he played 263 games in the top Tasmanian footy leagues across three clubs, kicking 430 goals and representing the state on 11 occasions.

Then coaching came knocking.

First as an assistant at North Hobart, then – like Henriksen – in the junior development area with the Tassie Mariners, before scoring a gig in the AFL at Melbourne from 1999 to 2007, then Hawthorn under Alastair Clarkson during a golden era from 2008 to 2016.

A club, not coincidentally, packed with coaches and staff who had been former school teachers.

“For me it’s just been an extension of teaching into a sport I love,” Fagan says

I love teaching, I love footy. So I’m able to do both things as a full time job which has been pretty cool for the last 26 years.

“I think we’ve got 10 coaches and I wouldn’t necessarily want them all to be teachers, because it’s good to have people from different backgrounds.

“But it’s important to have teachers who understand learning, and can help educate people about that because all we’re trying to do with our players and all we’re trying to do with our kids is teach them how to learn.”

It’s a concept the coaching staff calls a ‘growth mindset’.

The freedom for players to make mistakes and not be punished for doing so. The freedom to use those mistakes to make themselves better footballers, and more importantly, better people.

It’s a concept that won Hawthorn a bag of flags.

And it’s one that has the Lions on the precipice of an historic Grand Final.

ALL ON THE SAME PAGE

MAKING MISTAKES wasn’t met with a pat on the back when Scott Borlace was on an AFL list.

The Lions development coach and, yes, former secondary school teacher from Adelaide, reckons things have changed since his time.

“I had one year in the AFL system and the way the coach motivated was by fear,” he says.

“So you’d go out to a session and you were scared to make a mistake.

“That’s the big shift for me. Training is learning.”

Borlace has joined Henriksen on the couch under the Gabba stands, along with Zane Littlejohn – development coach and former Tasmanian teacher – and Mitch Hahn – ex-Bulldogs star who’s spending his spare time getting a teaching degree.

They’re a tight-knit group.

Together now for the better part of four seasons, they’ve overseen the development of raw kids with a bit of talent into genuine stars of the game.

Think names like Harris Andrews, Hugh McCluggage, Jarrod Berry and Eric Hipwood.

Kids once hopeful of just getting a game, now hopeful of winning the club’s first premiership since 2003.

And they’ve been taught through a united front.

“As a coaching group we have to make sure we have the strength to all be on the same page and deliver the same message,” Hahn says.

“What you’ll sometimes find is that a player might go to Zane for advice and Zane will say one thing. Then they’ll go to Scotty to see if they get a different answer, because they’re searching for the answer that they want rather than the answer they need to get.

For us, we need to not have that mentality that I can build a better personal relationship with a player by cuddling him after one of the other coaches has given him some advice that might be tough to handle.

“And that’s not to say we’re not being understanding about growth and about making mistakes. It’s about ownership of the problem and having that player embrace it for what it is.”

They’re a confident bunch that believes in their teaching theories, forged in the classrooms years ago and now used at the highest levels of the AFL.

They share articles with each other about new ways to educate, they put together class plans, and encourage each other as much as they encourage their players.

And they’re constantly adapting.

In their time as a collective, their development teams have won two premierships and made another finals series, with a mix of young players on the way up and older players on the way out.

“Last year I had Ryan Bastinac, Lewis Taylor, Nick Robertson, Josh Walker – we had a bunch of guys who had played a fair bit of footy experience where our coaching had to be ‘c’mon now, you’re better than this’,” Hahn says.

“Now we’ve got a Dev Robertson, a Keidean Coleman, a Brock Smith, where we have to create more of an educational environment.

“And that could change mid-year depending on what’s happening at AFL level.”

While the ultimate club goal is to put together a side that can challenge for a flag, these four men from four different states and with four similar – yet at the same time incredibly different – backgrounds, are aiming to develop the individual as much as the team.

Because the latter result relies so heavily on the former.

“Our job as coaches isn’t to get you a game. Our job as coaches is to build you a career,” Littlejohn says.

“We’re not worried if you’re playing round one, we want to build you a 200 game career. That’s our job.

“You know you look at Geelong, although they won flags in ‘07, ‘09, ‘11, they played a lot of footy together in the VFL.

“People say they’re AFL stars, but they did this together as a group through the lower levels.

“That’s the type of thing we want to see.”

It’s a juggling act, of teaching, of coaching, of acting as psychologists and as mates. And it’s a battle of managing expectations and egos.

“All of us have egos,” Hahn says.

“You might have a veteran with 250 games under his belt and his ego is nothing compared to a No.67 draft pick who’s like a dog to a bone.

“How we manage those guys to get back to what our primary focus is the challenge, to come back and play your role and live the trademark.”

A challenge made easier by the veterans the Lions have brought in on the field over the years.

“Hodgey was the perfect example of that,” Borlace says.

“He came here at 34 and he was working on his game as much as our kids were. He was still trying to get better at the end of his career.

“Using Mitch Robinson as an example, for him it was about opening up his mind to learning a new role, learning new things, and that if you still work hard at 30, you can still get better.

“And the proof is there with Mitch that he embraced that.”

Make no mistake – these coaches see their AFL stars as students. Their classroom is the training field and the club meeting room, their field trips – most years – are on a Virgin flight from Brisbane to Melbourne, or Adelaide, or Perth, to see if their prac work is paying off.

They want to be the top of the class.

“The good students are the ones that have got a growth mindset that they want to improve,” Fagan says.

“They don’t like making mistakes or failing but they understand it’s a necessary part of learning and it’s all a part of getting better.

“The guys that can do that and move on pretty quickly are the guys that can adjust to this environment better than the guys that take too long to forgive themselves.

“You don’t want them to keep making the same mistakes but you want them to understand that all of us in our lives make mistakes - and it’s what you do about it and what you learn from it that matters.”

THE NEXT GENERATION

THE MOVE UP from the southern states is harder than people think.

Brisbane has a different culture, a different mindset. In Victoria, you can approach anyone to talk about the AFL and they’ll chew your ear for an hour.

But here, that reverence for the game is almost non-existent.

“Sometimes it helps to be out of the spotlight but sometimes you want the pressure of Melbourne so the guys understand what that environment is,” Fagan says.

“So we sort of have to bring that to the place in some degree. There always needs to be a balance between comfort and discomfort, you don’t want them too comfortable but you also don’t want them too uncomfortable, it’s about finding that zone.”

A lack of comfort in Brisbane is one of the reasons so many players in the past left the club for seemingly greener pastures. The go-home five – Elliot Yeo, Billy Longer, Patrick Karnezis, Jared Polec and Sam Docherty – are still talked about around the club.

But they’re not talked about in the hushed, embarrassed whispers that used to echo the halls of Gabba. They’re talked about as an example of what’s no longer happening because of the investment in off-field leaders with shared experiences of moving away from home – all the way from CEO Greg Swann at the top, to the development coaches in the rooms.

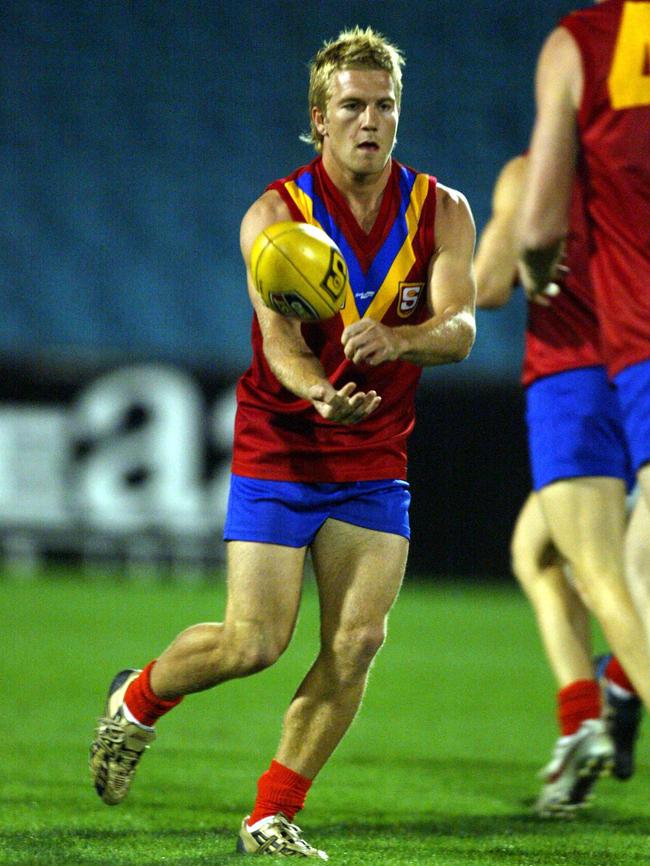

“When I first got here most of the coaches would get you over for dinner and you’d meet the families and they just created a really welcoming environment,” McCluggage, a star on the rise who was coached by Henriksen at junior levels, says.

I think having something in common with someone always helps. (Henriksen) coached me in the top aged Vic Country team along with probably four or five of the boys so just having that prior relationship with him and moving up with him at the same time I’m sure helped him as well as me to settle in.

It’s an example of the small world theory.

McCluggage is from Allansford, about half an hour down the Princes Highway from Terang.

His two uncles are teachers, including Ryan, who coincidentally did his teaching rounds at Terang College in 2003, under the watchful eye of Henriksen.

“I went to boarding school where you’ve got to build close relationships with the teachers because they’re quite involved in what you do, so to move up here and have a lot of coaches that have that (teaching) background and understood the side of building relationships and being a good role model on top of the footy side of things really helped,” McCluggage says.

“Guys like Henry and Zane, they’re great teachers for the younger guys in the Academy and do more of that teaching aspect of things whereas we’ve got guys like Jed Adcock and Ben Hudson who have been in the AFL system, so they understand what it takes at that level.

“There’s no one way I think that people should go about it, I think it’s good to have both sides of it, the educational side of it and the natural sort of footy side as well.

“But yeah, when you come in (to the club) you have to learn the culture side, learn structures, learn how things work around the club and you have to focus on the big picture stuff rather than the small stuff – I think that’s when the teaching side of things really helps.”

And, crucially, it’s inspiring players to look to a similar path, with the likes of Harris Andrews, Jarryd Lyons and Sam Skinner all doing part-time education degrees so they have a ready-made career after footy.

“When I played, I never had any plans of studying but I look back now and think ‘gee I wish I had have done this degree back then’,” Hahn, a 181-game veteran of the Bulldogs, says.

“I didn’t have three kids, I wasn’t working a full time job, I had plenty of hours in my day.

“Football has developed and changed over a period of time from when I first started in 2000 to what it is now, a lot of it becomes that growth mindset. When I was playing it was ‘do this and do it properly’.

“If I knew then as a player what I know now as I coach, I would have been a much better player.”

KEEPING IT SIMPLE

AS MUCH AS THE AFL IS about complexities and taking things to a new level, looking back is just as important as looking forward.

“The three man weave still gets a run,” Henriksen laughs, describing a training drill most footballers would have first seen in their pre-teens.

“There are drills here that we do with the witches hats that I used to do with the primary kids.

“Sometimes you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. The AFL players think it’s like gold because it’s something they would have done in grade one. But that’s their childhood in them too. You need to remind them sometimes of why they love the game.”

Variety is key. Not all footballers learn the same, just as not all students thrive from teachers standing at the front of the classroom pointing at a whiteboard.

“We really vary our meetings and change them and evolve them to keep players attentive and involved,” Henriksen says.

Anyone who has been in a footy club knows it’s a very structured place, but we always want to be coming up with ideas that can spice things up and make sure things don’t go stale.

“And coaching is negotiation. It’s give and take. Players love the coaches listening to them and taking on their advice. I think they get a kick out of that. We can’t just sit here and say ‘we know it all’ because once you do that you’re f---ed. Advice goes both ways.”

This isn’t just about the results on the field.

This is about building a culture – and building men the club can be proud of not only for their time on the field, but for the time they spend off it once their careers are over.

“Patience and empathy,” Littlejohn says.

“They’re not all going to get there at the same time. And that’s something I learned through teaching. When I was coaching I don’t think I had that. It’s something I picked up through teaching. Patience and empathy.

“We want to set you up to succeed.”

WE NEVER FORGET

PETER AUCHETTL WAS THE principal at Terang College that day back in 2005.

He was the one that got the call in the middle of the night. He was the one that sat with the close family friends in the early hours of the morning, and came to Henriksen’s door at 6am.

He was the one who privately wept in his office, before putting together a plan to look after his students, his teachers and his community and lead his staff and the town through its darkest days.

“We had a staff meeting first, then I had my own moment in the office by myself, and then we fronted the school,” he says, with a voice that instantly takes me back 16 years.

“It was extremely difficult. The staff reacted across the entire spectrum of that grieving cycle. Some were quite stoic, others broke down - there was clearly a lot of support for one another.

“But I remember quite clearly wanting to protect you guys. The students and ex-students who were grieving.

“I remember someone said that you were all gathering down in the avenue (the tree lined main street of Terang) so I think I got Henry to go down and grab you all and bring you to the school so we could all be in once place. Away from the media, with people who could look after you.

We just wanted to protect you.

Auchettl says that day didn’t change him – but he often reflects about what those two kids might have become.

Teaching, he says, is just about helping people grow, seeing them become the person they want to be, living the dreams they want to live. And that includes people like Paul Henriksen.

“The thing about Henry is that he was highly organised, driven, he had exceptional people skills. His glass was always half full. I never had Henry come to me complaining. It was always ‘let’s move on and find an answer’,” he says.

“He was very passionate about his teaching. He took pride in his craft.

“And he was very emotional about having to leave his community.”

Henriksen has a new community now.

It’s vastly different to what he was used to in his comfort zone, but the principles are the same.

“There’s always times when you reflect on the situations and the organisations that you’ve worked in and how they’ve moulded you as a person,” Henriksen says.

“Your life will be fine as long as you can help and support enough people to get them to where they want to get to.

“I get more of a kick in getting people where they want to get to.

“The players never forget, and we never forget the players.”

MORE FROM KYLE POLLARD

■ LONG WEEKEND: Untold story of VFL’s first Queensland game

■ IT SHATTERS YOU: The lasting impact of our road toll

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout