Sacked podcast: Barry Hall on his difficult childhood, leaving St Kilda, his axing from Sydney, and how fatherhood has changed him

Barry Hall was a gifted young boxer but a decision to pursue football instead led to a relationship breakdown with his father, and it may be why he always played on the edge.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Barry Hall still can’t explain the extraordinary drive that pushed him to live out a childhood dream of holding up an AFL premiership cup.

But he knows what chasing that dream cost him.

His chosen career path fractured his relationship with his father; his mistakes cost him friendships; his short fuse inflicted collateral damage on others.

It was only in the latter stages of his headline-grabbing, wildly successful 289-game, 746-goal AFL career that he was finally able to unpack some of those demons.

Hall confessed to the Herald Sun’s Sacked podcast he didn’t enjoy around “80 per cent” of his 16-season career.

He also had to endure a post-footy identity crisis which left him lacking motivation, despondent on the couch, and topping the scales at one stage at 125 kilos.

It’s been some sort of journey on and off the field to the point where the now 43-year-old husband and father of two young boys says he is the happiest he has ever been.

Some of his complex issues relate to his tough upbringing in Broadford, almost 70 kilometres north of Melbourne, and in particular a strained relationship with his father, who refused to talk to him “for years” after Hall chose football over boxing as a teenager.

“I had a difficult childhood and I have (since) done some study on these things,” Hall explained.

“From the age of zero to seven is your programming as a child.

“I had a lot of underlying issues which I don’t want to go into too much … because I take responsibility for my actions as an adult.

Kayo is your ticket to the 2020 Toyota AFL Premiership Season. Watch every match of every round Live & On-Demand. New to Kayo? Get your 14-day free trial & start streaming instantly >

“I don’t want to use it as an excuse.

“Getting reported, getting into fights off the field, the anger issues … I had to understand why I had those issues.

“You have to understand it to be able to fix it.

“It took me getting sacked (by Sydney in 2009) to go to the Western Bulldogs to really do some work on myself.

“I was finally prepared to listen and open my mind and accept responsibility.

“I signed a document … it was a commitment that I was not going to let my past dictate my future.”

‘WHEN THE S*** HIT THE FAN’

Having his two sons, Miller and Houston, with wife Laura changed everything for Hall.

He “mauls” them with kindness.

“I kiss my kids 20 or 30 times a day,” Hall said.

“I have so much love for them. I just don’t know how you could not do that as a father.”

All he knows now makes his experience with his father even more bewildering.

“I was boxing at one stage and was 15 about to turn 16,” he recalled.

“I really didn’t want to do it. I wanted to play footy because my mates were.

“I told my Dad I didn’t want to fight anymore. And that’s when the s*** hit the fan.”

His father envisaged Barry fighting for titles instead of fighting for the footy.

“He didn’t speak to me for years after that, which you might think is an exaggeration. But sitting at the table, (there were) no words, no nothing,” he said.

“Dad was trying to live his life through me … without blowing my own trumpet, I was good at it.

“(Quitting boxing) was not good news for him and it wasn’t good news for our relationship.”

The “brain farts” – as Hall calls his on-field transgressions – have a genesis in his childhood, though it took him years to understand this.

But his determination shone throughout.

“I got selected for the Murray Bushrangers in Wangaratta with my parents not on my side,” he said.

“How do I get there? It’s two and a half hours away. I had to start work in a panel shop around the corner, sweeping floors to save up enough money because in Victoria at 16 and nine months you can get your ‘L’ (plates) for your motorbike.

“I bought this s*** motorbike and started riding up and down the freeway for training and luckily I got selected.”

Those roads led him to St Kilda.

MORE BARRY HALL:

Barry Hall lays bare impact of depression

AFL great Barry Hall targets NRL giant Nelson Asofa-Solomona if SBW falls though

Barry Hall declares he would ‘love’ code war rematch with Paul Gallen

‘WHO AM I NOW?’

When Barry Hall retired from football at the end of 2011, he didn’t expect one more sledgehammer to hit him.

This time it related to a post-footy identity crisis.

He ate the wrong foods, drank heavily, and sat on the couch unwilling to leave the house.

“When I retired I went through some real struggles,” Hall said.

“There is such a thing called an identity crisis, which a lot of elite sportsmen and women get.

“You wake up after you retire and you think ‘Who am I now’?

“I identified (as a footballer) for so long. I had a goal to get up and train seven days a week and all that is gone.

SUBSCRIBE TO SACKED HERE

“All your structure is gone, your identity is gone. You fall into a state of depression, (thinking) ‘What am I now if I am not that’?”

He couldn’t drag himself out of the rut.

“I put on a heap of weight, I got up to 125 kilos,” he said.

“I was eating crap, I was drinking every night and when I drink, I don’t just have a couple, I strap it on.”

One morning he decided to tackle it head on.

He dragged himself out of bed at 6am, went to the gym and charted the pathway to where he is today.

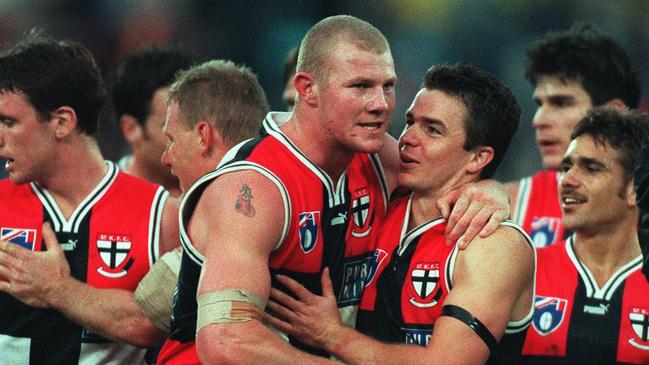

FLASH OF BRILLIANCE IN ‘97

Hall was only 20 when he almost became a St Kilda Grand Final hero in an explosive five-minute burst during the second term of the 1997 playoff against Adelaide.

He kicked three goals in that time, edging the Saints tantalising close to that elusive second flag.

Yet in keeping with his footy at the time, he faded from the narrative, as the Saints blew a halftime lead to go down by 31 points.

Hall confessed he didn’t care enough about the loss at the time.

“I just thought we would be back the next year … I was pretty young and took it all for granted,” he recalled.

Of his own cameo, he said: “I would dominate a game for 20 minutes then you wouldn’t see me for the rest of the game. I had to learn to train myself and (train) my mind into how to play a good consistent game of footy, which I eventually did down the track.”

NEEDING A CHANGE

A chat to ex-Saint turned Swan Tony Lockett convinced Hall the anonymity of playing football in the Harbour City would benefit him.

“A trade had to be done, but I signed a heads of agreement (midseason) saying (the Swans) would put their best endeavours forward to get me there,” Hall said.

In his last game with the Saints in the final round of 2001, he kicked the winning goal against Hawthorn.

“Stevie Milne laced one out to me and I marked it. It was a floater but it went through. It was a pretty good way to end.”

Hall made his mark from his first season with the Swans, even if the coaching turmoil that had plagued him at St Kilda seemed to follow him north.

Paul Roos was appointed caretaker coach after Rodney Eade was sacked midseason.

Footy’s worst kept secret was that Terry Wallace had reached an agreement to coach Sydney the following year … until the Swans started winning.

“I guess the way we reacted and played under Roosy almost forced that (the board’s decision to renege on the Wallace deal),” he said.

“I am not sure how much money the club burnt (on Wallace), but it was a good decision in the end.”

Hall’s career transformed in Sydney.

He won the club’s goal kicking award for seven successive seasons (with hauls of 55, 64, 74, 80, 78, 44 and 41) before his final season at the club exploded in controversy in 2009.

SKIPPER AT SYDNEY

As a kid, Hall used to pretend he was holding up in the premiership cup in his backyard.

The cup back then was a block of wood.

In 2005 he was the Swans captain holding up the premiership cup, signalling the end of the club’s 72-year drought.

He could barely lift it.

“I was getting injections to get through games, so to hold the cup up was quite a struggle,” he said.

His voice still quakes when speaking of 2005.

“I still get emotional about it now,” he said.

“It is something no one can ever take away and the Swans have it in their trophy cabinet (forever).”

WALKING TIME BOMB

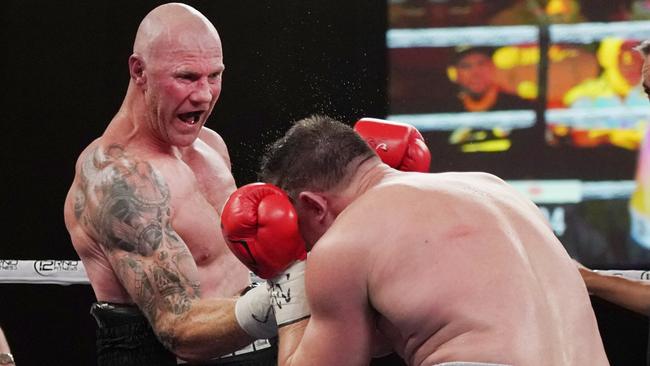

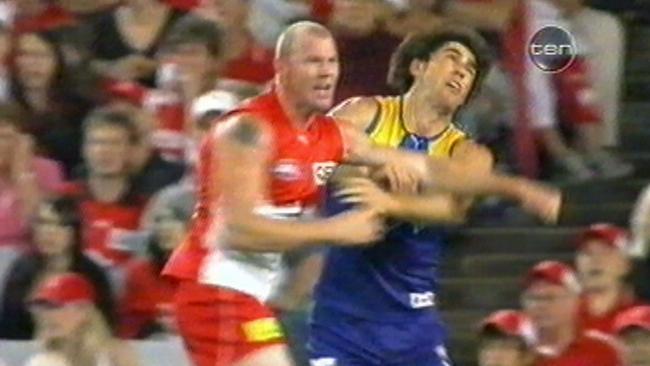

Hall’s life changed on April 12, 2008; it was the same for West Coast’s Brent Staker.

Each is reminded on an almost daily basis of what happened at ANZ Stadium.

Hall was “wound up” before the clash: “A few things happened off the field, nothing bad. But if you keep blowing in a balloon, it will burst,” he said.

“It was one of those days when it was a ticking time bomb.”

In a pique of anger, Hall threw a sickening round-arm punch that smashed into Staker’s jaw.

He concedes now the blow could have killed Staker.

“I regretted it straight away. As soon as I watched it on the big screen, I thought ‘I’m in a bit of trouble’.”

The “karma bus” struck. Hall later broke his wrist after being pushed over the boundary line into the signing.

His seven-match suspension matched the same amount of time he missed with the injury.

But the fallout not only impacted on him, but also on the victim.

“I am not a bad guy,” he said.

“One thing that did bother me is the after-effects from (Staker’s) point of view, not mine, because what happened to me, I deserved.

“To his credit, when we met up, he said ‘That’s fine’. I certainly wouldn’t have been as warm as he was if I had been him.”

‘YOU WILL NO LONGER PLAY AT THIS CLUB’

Hall copped a week for an “attempted strike” on Collingwood’s Shane Wakelin in his second game back.

The final straw came midway through the 2009 season when he punched Adelaide’s Ben Rutten.

“That’s when it came to a head,” he said.

“I just gave him (Rutten) a whack.

“It was another brain fart. I was back to square one.”

Hall had been undergoing psychological sessions, but spent most of the time “rolling my eyes … saying ‘how long have we got here’?”

The Swans had had enough.

He was summoned to a meeting with Roos, assistant coaches John Longmire and John Blakey and chief executive Andrew Ireland.

“It got a bit heated,” Hall recalled of his standoff with Roos.

“I was a premiership captain of the club and (Roos) was not answering my phone call.

“I knew something had to happen from a club perspective. I was upset because it strained so many relationships.”

Hall suggested to them he would “do his time in the twos … and I will come back.”

Ireland told him bluntly: “You will no longer play for this football club”.

“I said ‘pay me out and I am gone’.

“I spoke with my management and they said it is probably better off if we resign rather than be sacked.

“We were all smiles at the press conference like we were one big happy family but at the time it was pretty tense.”

Roos and Hall have “sort of moved on”, working alongside each other for a period at Fox Footy.

“I was just pissed off with the way I was being treated, Paul Roos has accepted that and admitted that to me, so I am happy with that”.

OLD DOG, NEW TRICKS

Hall figured he had played his last AFL game.

“I thought ‘what club is going to want a 34-year-old who has a bit of a chequered past?’,” he said.

“(But) having been sacked by the Swans, I certainly wasn’t comfortable leaving the game like that.”

Eade convinced him to join the Western Bulldogs.

“He said ‘mate, you are still playing good footy, let’s just have an enjoyable couple of years … let’s not do anything stupid.”

Hall would complete his AFL career at a third club, booting 80 goals in his first season and 55 in an injury-interrupted second season.

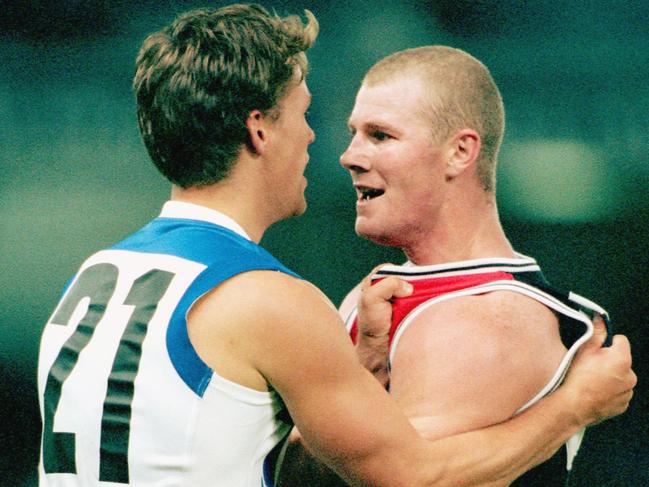

A flicker of anger came when North Melbourne’s Scott Thompson pushed him over during a game in 2010 when he was tying his shoelaces up.

“I didn’t lose the plot, I simply put him in a headlock,” he said.

“If I lose the plot, I don’t put people in headlocks.”

The Dogs didn’t win a flag in his time there, but Hall got something almost as rewarding.

He got a better understanding of his anger issues, and how to manage them.

TOUGH TIMES

Hall was left without income in 2018 when he was sacked from Triple M for an inappropriate on-air comment.

“All the endorsements I had, and every other revenue stream I had was gone,” he said.

“I had no money coming in. We weren’t broke. We had a roof over our heads and food on the tables, but it was challenging.”

Two years on, he has got his life back and has turned his hand to helping others.

Hall joined forces with leadership/culture coach Richard Maloney, of Quality Mind, and North Melbourne star Shaun Higgins to establish a Facebook support group – Blokes United – to assist men during Melbourne’s lockdown period.

It has grown into a network of almost 13,000 members.

Zoom conferences on Facebook and Blokesunited.com.au provide workshops on leadership, fitness, diet and mental health advice.

“It’s tough times for people in Melbourne and we thought there needed to be a platform to support a network for guys,” Hall said.

“It is almost a sense of therapy for me. I like helping people and it makes me feel good about myself as well.”

THE NEXT CHAPTER

Hall doesn’t deny the past, but he is genuinely excited by the future.

“I have made mistakes and I have accepted responsibility for them,” Hall said.

“I have done some really crappy things that I regret, but it has put me in the position I am in now.

“I know exactly who I am. I am a big believer in creating your own environment so that I don’t have s*** around me. I only have honest people.

“They are not fake; they are all real and they have got my back.”

Originally published as Sacked podcast: Barry Hall on his difficult childhood, leaving St Kilda, his axing from Sydney, and how fatherhood has changed him