AFL in the midst of a mental health crisis, Sydney Swans Hall of Famer Tadhg Kennelly says

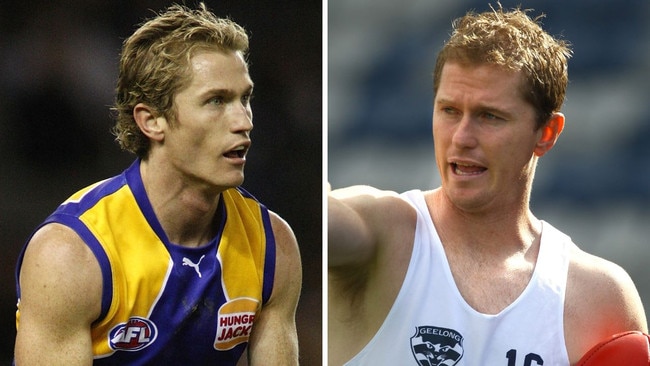

As the AFL reels from the death of Adam Selwood, months after his brother took his own life, a Swans legend has lifted the lid on the game’s “suicide crisis”.

AFL News

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

An AFL great fears further tragedy is inevitable as the game battles a mental health crisis that’s led to a string of deaths by suicide among former players.

Sydney Swans Hall of Famer Tadhg Kennelly said the shock passing of Adam Selwood at the weekend, just months after his twin brother Troy took his own life, is “an absolute tragedy”.

“The Selwood family have been one of the cornerstones of the game of AFL and have given everything to it,” Kennelly told news.com.au.

“Joel, Scott, Adam and Troy are the embodiment of grit, humility and heart. They were raised on the values of loyalty, strength and brotherhood. It’s heartbreaking for the family, it’s heartbreaking for AFL and it’s heartbreaking for the country.”

Adam’s death is the latest in a string of suicides of former players, sparking questions about the adequacy of support programs for past and present participants in AFL.

Both the league and the AFL Players Association have played down talks of a crisis, each detailing their raft of mental health initiatives.

Kennelly said those programs are clearly not working.

“Adam and Troy, Cameron McCarthy, Shane Tuck, Danny Frawley, Shane Yarran … they each played at the highest level, left the game, and then died by suicide,” he said.

“The system we’ve built that’s supposed to catch them didn’t work. We have a problem. I think it’s fair to call it a crisis.”

At the weekend, Beyond Blue chief executive Georgie Harman said the sheer number of different programs and projects meant the landscape was “complex and cluttered” and “confusing” for players seeking help.

“I think it’s time to step back, look at what’s out there, look at whether or not it’s working, look at how it’s connecting and ensuring that people understand that support is available.” Ms Harman told The Age.

Sarah Tillott, an expert in resilience theory, particularly through the lens of sports as a protective mechanism, who spent two decades in the university sector, agreed.

“There are a lot of buzzy programs out there, but they lack the evidence behind them,” Dr Tillott said.

“There’s a lot of what we call ‘edu-tainment’ – a bit of education but a lot of entertainment. It looks good but whether it actually achieves anything is debatable.”

Kennelly called for stronger leadership to overhaul the approach to mental health in the game, to drive a cultural change that delivers actual positive results.

The AFL has an important opportunity to “step up and lead”, he said, adding: “One life is too many. Six is unbearable.”

After playing 197 games with the Swans, including during its 2005 premiership year, he is intimately familiar with the kinds of pressures footballers face.

“The game is extremely demanding. It’s ruthless, as all professional sports are, but that’s where they’ve got to be. It’s a billion-dollar industry.

“As a player, you’re constantly on edge about your performance. It’s important to be when you’re an athlete because if you lose your edge, your opponent can get hold of you. So, the obsession is instilled in you.”

But it was retiring that presented the biggest challenge – one that many footballers face.

“When your career finishes, it’s a shock to the system,” he said.

“A lot of people talk about the identity loss. There’s a focus now on trying to help players not tie up their identity with the sport, but it’s very difficult not to.

“Since I was a kid, all I ever wanted to do was be a professional footballer. When it finishes at 34, no matter how much you think you’ve prepared, it’s really tough.

“I mean, everywhere you go, people ask you about your football career and your time in the game, so it’s hard not to attach your identity to it.

“And no longer being part of an organisation, of a community, is tough too. You lose the closeness and the magic of those connections. You miss that.”

Kennelly credits his wife and in-laws with “really putting their arms around me” when his playing career ended, saying he had “some really strong support people” in his life.

“I wonder where I’d be without those people,” he said. “I’m one of the lucky ones.”

He again needed support when he lost his job as an assistant coach with the Sydney Swans, he revealed.

“I was going through a very, very difficult time. I lost my job and it all played out very publicly in the media, and I was in a dark place. I was not in a great headspace.”

His friend David Eccles kept on his back during that rough patch, refusing to leave him alone.

“He called, he knocked on my door, he pretty much dragged me out of the house. He took me to get a coffee, to go for a walk, to do a bit of exercise. And we just started talking. I was able to start coming out of the darkness. I started looking forward more.”

That experience planted the seed of an idea for the men, who took the simple approach to support to launch WNOW – When No One’s Watching.

The organisation holds weekly catch-ups for men, which includes a sunrise exercise session, a trust circle where participants can talk about anything that’s worrying them, and then a group coffee.

“The spirit of it is guys looking out for each other.

“Even if someone doesn’t share, there’s a benefit I knowing that if they ever have a problem, they do actually have a space to talk about it.”

Now, each week, men gather at 56 different locations across the country.

“The change we’re seeing is pretty incredible given the approach is very simple, and we need more of these types of things,” Kennelly said.

“We need to get people together to connect. Connection for me has always had the biggest benefit. It’s about building mateship, which I think we’re losing in society.

“When you have mateship and connection, there’s a greater willingness to open up and discuss your issues or concerns.”

Dr Tillott said evidence-based approaches are crucial and called for a focus on resilience-building.

“I don’t think resilience is very well understood and this is an opportunity to do better,” she said.

“We can have a tick-box approach or we can do it properly. We need programs that deliver on-the-ground behavioural change strategies that are truly evidence-based.”

Footballers face all the expected challenges and risk factors the broader population does, with some added pressures on top, she said.

Someone who isn’t equipped with the skills to communicate, resolve conflicts or regulate their emotions, and who doesn’t feel comfortable connecting and being vulnerable, could be in a precarious position.

Advocates want a greater focus on mental health awareness and support at a community football level.

Tackle Your Feelings does just that, running free 90-minute mental health training programs, with 15,000 participants from 1500 community clubs taking part since its inception in 2015.

“It’s delivered by a local psychologist and the program aims to help participants, build the skills to understand mental health, recognise signs and symptoms of mental health, and then be able to respond to someone who may be struggling,” program manager Adam Baldwin said.

“It’s about taking mental health, which some people may not be comfortable talking about, to places they’re comfortable and where they have existing strong relationships with people they trust.”

Across the board, men are less likely to seek help when they’re struggling, which contributes to the disproportionately higher risk of suicide.

Three quarters of those who take their own life in Australia are men.

Vita Pilkington is a fellow at the University of Melbourne and works with youth mental health research organisation Orygen, where for five years she was part of the elite sports unit.

Unique approaches are beneficial for men, many of whom would probably bristle at the thought of sitting in a psychologist’s office and bearing their soul to a stranger for an hour.

Ms Pilkington said subtle and indirect supports that are not alienating and meet men where they’re at are highly effective.

“That’s the whole idea behind Men’s Sheds, for example,” she said.

For all its investment in mental health programs, the AFL “clearly” still has a problem when it comes to how support is offered to present and past players, she said.

“We’re talking about people who are required to perform and who need to be seen to be in peak form – they need to be able to walk onto the ground and handle anything,” Ms Pilkington explained.

“Imagine a young player in a footy club who really wants to be selected for a game this week. Maybe he won’t mention that he’s feeling really down or really anxious in case, in good faith, the club doesn’t pick him in a bid to prevent exposing them to more stress.

“That approach is so well-intentioned but it really reinforces that fear of speaking up. You can completely understand why someone might not say if they’re struggling.

“The barriers are understandable. It raises an important and tough question about how to respond to mental health in these high performance environments.”

Some cashed-up AFL clubs have world-class programs in place, with mental health professionals on staff, including clinicians, Ms Pilkington said.

“They’re present at training and games, they’re highly accessible, they have good relationships with the players,” she said.

“The support can be provided in a really informal way, which is pretty critical in sport. Someone who knows you, know the club, gets the pressures, that you can go have a chat with is very likely the model.”

But not all clubs are in a position to offer that kind of resource.

Acclaimed psychiatrist Patrick McGorry, renowned for his development of early invention and youth mental health services, said athletes sit within the “peak age of risk”.

“And elite sport can come with unique pressures that heightens risk,” Professor McGorry wrote for The Conversation.

Suicide is the leading cause of death among all Australians aged 40 and under, with more than 3000 families losing a loved one each year.

Three quarters of mental health disorders emerge before someone reaches 25, and rates of mental ill health have risen 50 per cent since 2007.

Aside from the tragic personal consequences, the Productivity Commission estimates mental illness and suicide cost the economy $200 billion annually.

Originally published as AFL in the midst of a mental health crisis, Sydney Swans Hall of Famer Tadhg Kennelly says