Alastair Clarkson returns to coaching: Inside North Melbourne coach’s time away from football

Insider say Alastair Clarkon was trying to live ‘three lives’ before taking a break from coaching following a withering outburst. Get the inside story here.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Alastair Clarkson was broken physically and mentally.

He had reached a point where he could no longer carry the burden of fighting the allegations levelled against him that he vehemently denied while remaining as the coach of the North Melbourne Football Club.

It was early May and Clarkson’s balance in his life, which had always had an equilibrium, up-ended out of his control. Something had to change.

He couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t exercise. His decision-making was clouded for the first time in his professional life.

He was under duress battling severe physical pain.

Clarkson was going through entire nights without sleep.

At best he would catch a few hours.

It had been eight months since he, Brisbane coach Chris Fagan and former Hawks player welfare manager Jason Burt had been accused of mistreatment and racism from several former Hawthorn First Nations players and their families.

All three fiercely denied the allegations but felt powerless to publicly launch counterclaims while an AFL investigation was being conducted at a painstakingly slow pace.

Clarkson’s daily regimen of running had nourished his mind and his body ever since he was a kid growing up in Kaniva, in Victoria’s Wimmera.

But given all that was happening in his life, he couldn’t find the time to hit the pavements and when he did, he was in pain.

He was busy coaching the Kangaroos by day and dealing with a myriad of meetings and phone calls with his legal team at night as he fought to clear his name.

And for almost the first time in his AFL senior coaching career spanning almost 20 years Clarkson was second-guessing himself.

His mental health was on the brink; his body was almost the same as he battled debilitating pain in his back and legs.

The Herald Sun understands Clarkson sought several opinions on his ailments, and at least one recommended major back surgery. He didn’t take that option up.

As a strong alpha male weaned on hard work and ploughing on regardless, he was reluctant to ask for help … until he had no choice.

“I was on a little bit of a downward spiral and I needed to get myself right,” Clarkson said.

“Ten weeks ago I came to the realisation I needed to be genuine to myself, my family and my football club and acknowledge those priorities were not being met.”

The AFL’s most successful coach of the 21st century – with four flags at Hawthorn before a painful exit in 2021 – had no choice but to step off footy’s “treadmill” nine games into a five-year coaching deal with North Melbourne.

Not even he knew if he would be back.

Fast-forward almost 11 weeks to now, and Clarkson will return on Sunday to coach the Kangaroos against Melbourne in what will be his 400th game as an AFL coach.

Here is how he fought his way back when some of those close to him feared he might not.

ROCKED

The allegations levelled against Clarkson – first aired in an ABC news report in grand final week and detailed in Hawthorn’s external review into the cultural safety of First Nations’ players – started a firestorm that consumed the lives of all involved.

The AFL independent investigation dragged on for months, long past its planned resolution by Christmas 2022.

Those close to Clarkson say he was living “three lives” in those early months – the coach working his “arse off” trying to fast-track the club off the bottom of the ladder; the person fighting like hell to combat the trashing of a brand he had worked so hard to build; and importantly the father, husband and friend who had a diminishing energy to be all three.

Jordan Lewis revealed months later that a service station operator had refused to serve Clarkson after the allegations were first made.

It wasn’t the only instance where he received cold shoulders from strangers during the early months of the saga.

Some came out in public support, including his former captain Luke Hodge. Others held back, fearful of any potential backlash.

As Hodge said on SEN: “The stress of being an AFL coach is unreal in terms of the toll it takes on someone, but he (Clarkson) had so much other stuff going on at the time with the investigation. He felt like he was handling it OK, but then he realised he wasn’t.”

TIPPING POINT

Given how all-consuming his life had become, Clarkson wasn’t taking many calls from those he normally spoke with.

For a person who thrived on relationships, he became more insular.

His wife Caryn sensed it, and played a key role in Clarkson putting his hand up for help.

Some have suggested his halftime spray to his team in the round 9 clash with Port Adelaide was a catalyst. Others insist it had been coming for weeks.

Port Adelaide kicked eight goals to one in a second quarter that would have driven the most mild mannered of coaches to the point of exasperation, let alone someone as combustible on game day as Clarkson.

North Melbourne insiders say this was the first serious burst of anger the coach had shown with his players to that point, albeit several people inside the room flatly reject the suggestion he threw a chair against a wall.

He did knock over two water bottles as he delivered one of the sprays that he was known for at times, especially in his early years at Hawthorn.

It came as soon as the players entered the rooms. Before they went back out onto Blundstone Arena, he took them into the privacy of the coaches’ room where he calmly explained why he had “cooked” them.

Part of his explanation centred on his belief that they were “better” than their efforts.

“Look, it was a poor performance and yes he gave them a halftime spray,” Todd Viney said. “But it was the build-up of everything … it had been coming for a while before that.”

The extent of the problem became evident four days later when Clarkson and his wife Caryn contacted Viney on May 17.

“She’s an absolute star,” someone close to the Clarkson’s said this week of his wife Caryn. “There had to be a circuit-breaker. She knew he needed to get some help.”

Clarkson explained: “Caryn and I were getting warning signals regarding my physical and mental wellbeing on numerous occasions, and May 17 was the day of realisation that I could only invest in my family, my club and my community if I got myself back to full health.”

A meeting was arranged with North Melbourne president Sonja Hood – who had coaxed him to the club eight months earlier – and Kangaroos chief executive Jen Watt, as they agreed to give him all the time he required.

“The pressure was enormous,” Viney said.

“He needed to get his health back — both his physical health and his mental wellbeing.

“We knew if he could do that, then he could start helping his family again, and he could help the footy club and help our players to become the best version of themselves.

“But he had to start looking after himself first.”

As embarrassed as he was initially, he knew if he didn’t step off the treadmill, the implications were far greater than four premiership points.

“So many people are relying on your presence and your direction and guidance, so it is very difficult to walk away,” Clarkson said. “That weighed heavily. In the end it couldn’t have weighed more heavily on me than needing to get myself right physically and mentally.

“There was a bit of embarrassment attached to that. But you shouldn’t be ashamed. You can’t do anything productive in life if you haven’t got good health.”

UNMASKED

Clarkson had been “wearing a mask” for eight months. Choosing to take it off might well be one of the bravest things he has done in his life, as it has shown others reluctant to seek help that there is a pathway forward.

Those around him were never concerned that he was in any danger, but they were worried that if he didn’t do something to address the way he was feeling, the pain would only escalate.

He ripped the mask off on May 17, and says it will never go back on.

Two weeks after he stepped aside from football, handing over to his mate Brett Ratten, the AFL announced the independent investigation into racism allegations had been concluded, with no adverse finding against any individuals.

Fagan released a press statement immediately; Clarkson wasn’t able to.

He was in the midst of a physical and psychological cleanse and was in no state to make a statement.

He wasn’t even sure if he would return to football.

“For the first four weeks of stepping away from the game, I lost my appetite even to watch footy, including the North games,” he detailed.

Viney believed his friend would return, but said the leadership of Hood and Watt ensured that Clarkson knew he had as much time as required.

“In my short time here I have seen that people are their No. 1 priority and they (Hood and Watt) were very forthcoming in saying you have got to do what you have got to do,” Viney said. “They encouraged him to take as much time as he needed.”

One of those close to him said that he lost the thing that had made him such a great coach – his defiance. He had to find it again.

Part of self discovery came from letting go of the very thing that had driven all of his life – the game that had been his voice and his vocation.

For the first time in his life he had stopped watching football.

He disengaged from the club for the best part of four weeks as he invested wholly and solely on his own mental and physical regeneration.

If he hadn’t, he might not be coaching on Sunday.

PROFESSIONAL HELP

Clarkson this week thanked a team of medical professionals who assisted in his recovery.

“With the help of Dr David Cahill, Dr Peter Parker and Professor Steve Davis, we have put in place strategies that have been pivotal to my progress, and these are ongoing needs I endeavour to address moving forward,” Clarkson explained.

He saw a range of professionals - including a neurologist, a chiropractor and osteopath - which highlights how Clarkson had to go to work on his body and mind as part of his healing.

His mental health care went hand-in-hand with his physical care.

It is believed there was no specific anger management as part of his treatment, but collectively strategies were put in place on a range of situational and stress mechanisms, which he will use for the rest of his life.

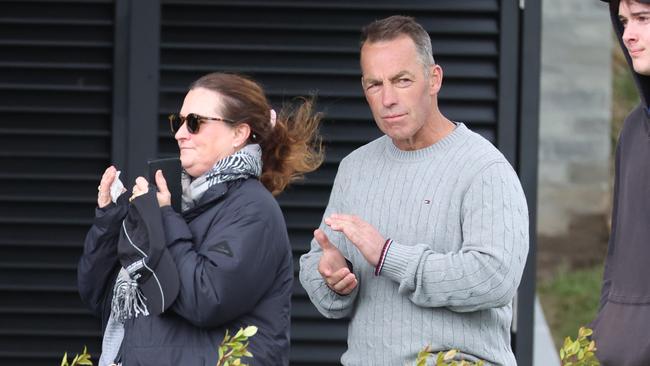

Initially, he spent a lot of time on the family’s farm on the Mornington Peninsula, which has always been his safe haven.

He spent time with his former Melbourne teammate and friend Garry Lyon, who has also bravely spoken about his own mental health issues.

Lyon said on SEN: “He came to the realisation that (stepping away) was absolutely the right decision for him and for his family, which is more important than anything else going on in the world.”

“He was just a bull at a gate which was why he was so successful. (He was) a bit of a ‘take no prisoners’ attitude outside of clubland, even though he was always very empathetic inside his club. I think this will be a really humbling experience for him.”

Slowly, Clarkson began to re-engage with those close to him. In time, he felt comfortable enough to travel to a number of different places in Australia that interested him to reconnect with people, including a trip to Brisbane to catch up with his daughter Stephanie.

The healing was almost complete.

LIFE BEYOND 400 GAMES

Part of Clarkson’s recovery plan included the carrot of a return to football, even though he wasn’t sure he wanted to for a period.

All that changed with a “light bulb moment” on Sunday, June 4. He was sitting back and watching the Kangaroos’ round 12 clash with Essendon when a kid called George Wardlaw – in his third game — suddenly had the blood pulsing through his coach’s veins.

“It was like a light bulb came (back) on for me when George Wardlaw played against Essendon, it was like I want to be involved in this kid’s career,” Clarkson said.

His former teammate and weekly running partner Mark Brayshaw knew his mate had regained his passion around six weeks ago.

“The prospect of helping to optimise the enormous potential of so many of those young players at North Melbourne was very important to him and in the end I think that prophecy of helping them realise their potential — not just on the field but off it — was an important reason why he got himself back,” Brayshaw said.

There was some science in the decision to stagger his return. Part of it was to ensure he did not do too much too soon. But it was also so that it wasn’t a distraction to the players and coaches in charge.

He first sat down a few weeks ago with the coaches, including Viney and Ratten, whom he says he owes a debt of gratitude, then the leadership group and then the entire group.

He met up with a few players individually, and recently took Robert Hansen Jr, Charlie Comben and Tom Powell to a match at the MCG.

Now he is back, how will Clarko 3.0 differ from the earlier version?

Lyon is convinced Clarkson will have more empathy and compassion, while Shane Crawford agrees, but still expects him to be as unrelenting as ever in the pursuit of success.

The defiance is definitely back. It’s a part of his DNA.

The man himself can’t wait to get back to work again. He wants to repay the club that gave him his first league chance and stuck by him all those years later when he needed help.

“I am in a much better space and have made some adjustments to the way I will live my life,” he said. “I am not 30 years of age anymore. I am 55 and I have had to make some adjustments to the way I live because if I kept living that way I might not have made 65.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Alastair Clarkson returns to coaching: Inside North Melbourne coach’s time away from football