Adelaide Crows Camp: Collective Mind directors Amon Woulfe and Derek Leddie speak to Graham Cornes

The directors of the company behind Adelaide's infamous 2018 pre-season camp exclusively reveal what happened and the catastrophic fallout.

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Test your knowledge of news, sport and pop culture in Brainwaves

- Read more from this week’s SA Weekend magazine

- How to get the most out of your Advertiser digital subscription

There is a moment in Amon Woulfe’s life that is forever etched in his memory. He is in the Adelaide Crows dressing rooms deep in the bowels of the MCG after the 2017 AFL Grand Final. With a Crows player sobbing on his shoulder, they resolve: “Never again.”

The room is awash with devastation. Players, staff, wives, families and friends are drowning in the disappointment of losing a match they were outright favourites to win – should have won.

The unfolding scene echoes the words of Anton Oliver, the All Blacks hooker recalling New Zealand’s elimination from the 2007 Rugby World Cup after a shock loss to France: “The feeling in the shed is like no-man’s land … there’s a sort of desolate decay and – I don’t want to dramatise it – the smell of death.”

Anyone who has been in the loser’s rooms on Grand Final day knows exactly what that feeling is. “Never again.” It was a pivotal moment that set off a chain of events that will forever be etched in AFL folklore.

LATEST: JOURNOS APOLOGISE OVER ADELAIDE CROWS CAMP CLAIMS

Four months later, with a sense of anticipation, the Crows embarked on “The Camp”. Much has been said about that now infamous pre-season camp held by the Adelaide Crows and Collective Mind in 2018 – from the slightly strange, to outright shocking. Some even blame it for the downfall of a once mighty club.

Now, after two-and-a-half years of relative silence, the directors of Collective Mind have not only agreed to speak, they have also provided exclusive access to documents, runsheets, photos, facilitator bios, clients, and first-hand accounts of what actually happened.

Woulfe and his work partner Derek Leddie, joint managing directors of the performance-based mindset training company, had once been rivals. A bachelor of political science with a masters in business and a basketball background that took him to the feeder level of the NBL, Woulfe’s expertise had been in the corporate world.

He rose quickly through senior management levels, responsible for organisational change and leading high-performing teams. But eventually he “burnt-out”, and stepped out of the corporate world to pursue more holistic disciplines of mindfulness and meditation, as well as becoming highly involved in working with programs in the areas of healthy masculinity and male rites of passage. He also works privately as a mindset coach for individual elite athletes in basketball, Australian football, and English football.

Leddie built a global, award-winning market research company, The Leading Edge, which was eventually bought out by a public company, leaving him the time and means to pursue more philanthropic and benevolent activities. His Yoga Foundation, for instance, is in its 12th year of delivering yoga programs to Aboriginal communities, prisons, hospitals and victims of rape and domestic violence.

Leddie won awards for his high-performance leadership and culture at The Leading Edge, and saw an opportunity to take that experience and build a skills-based approach to training and lifting performance in the mind that could be taught to anyone.

When Leddie and Woulfe realised their strengths complemented each other they collaborated under the banner of Collective Mind in 2016 and were contracted by the Adelaide Football Club in 2017 to deliver their renowned mindset program. While their core clients are predominantly from the corporate sector, Leddie had worked previously with the St Kilda Football Club in 2015-16 and more significantly with the triumphant South Sydney Rabbitohs in their drought-breaking premiership year of 2014. In a phone call that Leddie arranged between Rabbitohs’ star Sam Burgess and Crows’ skipper Taylor Walker, which Walker later shared with the Adelaide leadership group, Burgess generously said of the impact of the mindset program: “This is what won us the flag.”

Collective Mind worked with the Crows through the 2017 season, delivering monthly training sessions for the whole team and specialised one-on-one coaching for individuals. So satisfied was the Adelaide Football Club that it signed Collective Mind to a two-year AFL exclusivity deal, effectively shutting out interest from other AFL clubs.

Then-coach Don Pyke has since admitted that he made a critical mistake in not immediately confronting the demons of the Grand Final loss and debriefing the players involved. Collective Mind had recommended the club address it before the players’ exit interviews.

Leddie: “We probably went back to them four or five times. ‘You need to address this now. Don’t let it fester,’ we said. They didn’t take that advice.”

The end-of-season break was anything but pleasant for many of the players as they carried the pain, shame, grief and humiliation of the Grand Final loss through the summer. As a result, they presented for pre-season training in less than ideal condition – physically and mentally. Some were overweight, some sad, some angry, others guilty.

The 2017 season had been an outstanding one for the Crows, but their achievements were all overshadowed by the humiliation of the Grand Final. The club’s internal review determined the Grand Final loss was around three core issues: leadership, resilience and team connection. It was agreed the reasons were not physical, tactical or technical. The issues were the team dynamics not the mechanics. On reflection, the warning signs were there early. Pyke and the assistant coaches noted that the main training session before the Grand Final was the worst main training session of the year.

When the players eventually met for a Grand Final debriefing in November 2017, after their end-of-season break, some said the additional external pressures of Grand Final week made it the worst week of their lives. Some even said they were “completely cooked” before the game even began. And some can barely remember what happened during the game.

On Grand Final day, the Crows looked too slow and too tall. Their Richmond opponents swarmed all over them at ground level with frenetic pressure and pace. Adelaide’s GPS running meters, however, were down hundreds of metres. Richmond didn’t speed up, the Crows slowed down.

The Crows had beaten Richmond by 76 points in their last meeting before the Grand Final, and they won by 36 points in their first clash after the Grand Final. They were pretty much the same teams, so what happened on Grand Final day?

Leddie and Woulfe contend the players didn’t handle the mental stress of Grand Final day, and they didn’t stay connected under pressure. Their hearts and minds went missing, and their bodies simply followed.

In the cauldron of a Grand Final, Richmond’s bond grew stronger, and the Crows’ bond broke. Richmond chief executive Brendon Gale, reflecting after the Grand Final on all the work they’d done exploring connection through their famed Triple H cultural sessions that year, said “connection is our competitive advantage”.

Hence the Crows gave Woulfe and Leddie a brief to develop a plan for a pre-season camp that would focus on strengthening the resilience and connection of the team – factors the club hierarchy believed failed in the 2017 Grand Final.

It was a separate and far broader brief than the mindset program they had been working on through 2017, so both Collective Mind and the football club collaborated to develop a program addressing themes of “authenticity, resilience and connection” and how embracing emotional openness could foster a deeper team bond under pressure.

These were not normal components of the Collective Mind sporting mindset program. “We therefore went to the market to find specialists to deliver an impactful, experiential and proven program,” Woulfe says.

Woulfe and Leddie eventually co-developed a program which was approved by senior club figures including Pyke, head of football Brett Burton, and doctor Marc Cesana who cleared every player as mentally and emotionally fit to attend. Woulfe and Leddie say chief executive Andrew Fagan and the club’s board had full awareness of the program.

One of the club’s coaches pilot-tested a public version of a “rites of passage” program and both club management and Cesana examined and approved detailed program running sheets. The entire playing list of 45 players, Pyke, all assistant coaches, key high-performance staff and Burton were on site and participated in all sessions. “We’d never ask anyone to do something we haven’t done ourselves. Derek, myself, and almost every other facilitator on site had been through these programs,” Woulfe says.

In keeping with an internal club “warrior” theme, the program was called “Path of the Warrior” and split into three sections.

The first, labelled “Code of the Warrior”, was led by Andrew Cox from the Buman Experience. It was intended to introduce first- to third-year players to the foundational values and principles of a true warrior. Designed to upgrade the maturity of the younger players, it was facilitated by former Defence Force personnel and aimed at developing skills in presence, connection, authenticity and resilience. Their place in the heritage and lineage of the club was also impressed upon them.

The second program, called “Heart of the Warrior”, was led by Steve Dyer from Workplace Wellbeing Institute. It was for players with four or more years’ service who weren’t part of the leadership quorum. The Heart of the Warrior group was led by qualified counsellors. Woulfe and Leddie say this program intended to introduce players to the power of emotional openness in fostering team spirit – how a true warrior needed his heart and his “grit” working in unison – and was designed to build deep connections between the players, strengthen relationships and promote authenticity.

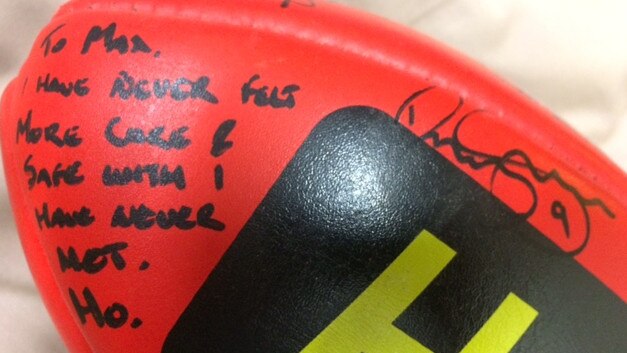

The third program, made up of the leadership group, Pyke and senior assistant coach Scott Camporeale, was called “Mark of the Warrior” and led by Gary Simpson, Wolfgang Wildgrace, and Max Witsenhuysen from Workplace Wellbeing Institute. Participants in this group were led through a “rite of passage” style program where they confronted and overcame “immature masculine” behaviours such as selfishness, entitlement, laziness, privilege, disconnection, lack of integrity, lack of respect and lack of discipline that had been holding back their performance on the field or around the club. Woulfe and Leddie say the rite of passage program was led by qualified counsellors and experienced facilitators, and “integrated healthy challenge and support to create a strong, emotive and resilient leader”.

One of the most contentious issues in the wake of subsequent criticism of the camp has been the qualifications of the facilitators and why it was not conducted by qualified psychologists. South Australian Greens MLC Tammy Franks even said the programs were run by “quacks”. It’s a criticism that offends Woulfe and Leddie.

It’s important to note that Collective Mind did not facilitate or deliver this camp, they co-ordinated it.

“The lead facilitators were tertiary-educated counsellors and psychotherapists,” Woulfe says. “We found qualified experts who had proven behaviour-change programs with decades of experience working with men, and who could work in a practical way with the emotional and relational dynamics of the team.”

One of the facilitators had 12 years’ service in the Australian Defence Force, including tours of Afghanistan and East Timor, and now runs corporate leadership and team development programs. He holds a diploma in leadership and management, diploma of workplace health and safety and a Certificate IV in training and assessment and physical training.

“We stayed well clear of any pathology, personal trauma, childhood issues and the like,” Woulfe says. “These issues are solely handled by their team doctor, personal psychologists, welfare manager and others, and we never have involvement in these areas. This camp was about performance, not pathology, and we brought in experts who could work with their hearts and build great men.”

The duo also questions a common belief that performance-based mindset training can only be conducted by psychologists.

“Thousands of leadership coaches globally train mindset,” Woulfe says. “Sporting coaches work on mindset, so do strength coaches, and some of the biggest name athletes and teams in the world have high-performance mindset coaches who aren’t psychologists.

“We are highly qualified and experienced to be mindset coaches, and we’ve found that what we do and what psychology does is complementary.”

Woulfe and Leddie provided SAWeekend with the programs’ daily timetables, which were detailed and extensive and framed around the words “theme”, “activities” and “outcomes”.

Underlying themes of resilience, emotional openness, healthy masculinity and a warrior spirit are dominant. For example, players were asked: “Where is my immature masculine behaviour still appearing in my life, on the field and in my game?”

The running sheets also allocated time to tap into the warrior spirit of martial artists. Black belt senseis led Aikido sessions and players were introduced to key concepts of Budo: The Path of the Warrior. Woulfe and Leddie say the days were long, busy and provocative but always ended with the opportunity for the players to ring home.

The organisers say the open, positive feedback from coaches, players and club management left them in no doubt the camp had been a success.

Player comments including, “It was the best camp they’d ever been on”, “wished I’d been able to do it earlier in my career” and “it made me a better husband”, further confirmed their belief it had been a success. Facilitators were told they were now part of the Crows family and offered tickets and dressing room passes to home games.

Quotes from key players reinforced the belief it had been a success. Team captain Rory Sloane said in March 2018: “I absolutely came back from that camp feeling like a better husband, a better son and a much better teammate than I was before I left on that camp. For me, the experience was unbelievable.” And this from then-captain Taylor Walker in March 2018: “The camp was one of the most beneficial and rewarding camps I’ve been on and I would encourage any of my best mates or family members to do the same thing.”

More significantly, former Crow Hugh Greenwood, a psychology major, whose mother had sadly passed away, spoke glowingly of the camp in an interview he gave to Advertiser journalist Richard Earle in August 2018: “I actually found it really rewarding as an opportunity to open up and at the time talk about the loss of the Grand Final and it was not long after Mum passed away. We weren’t quite sure what we were doing before we got there. I was more worried about getting up at 3am and 4am for a boot camp but we never did any of that.”

Woulfe and Leddie say no player or coach raised any objection to or had any issues with anything they were participating in during the entire camp. Several concerns filtered back to them in the days after the camp, but none sounded any alarm bells.

Curtly Hampton asked for clarification around permissions to use the Indigenous talking stick and Eddie Betts around certain Indigenous phrases used by lead facilitators. Woulfe and Leddie say they resolved this issue by providing a full report to the club and the Crows Indigenous officer detailing the appropriate permissions that were granted by Aboriginal elders.

Assistant coach Matthew Clarke asked for clarification around how the camp activities he experienced connected to a match-day experience.

Fellow assistant coach Josh Francou sought clarification around the club’s duty of care to players who were opening up about personal challenges. Both the club and Collective Mind told him that team doctor Cesana had cleared every player as mentally and emotionally fit to attend the camp, that lead facilitators were qualified to run these processes, and there was on-site triage process to cover any emergency – such as when forward Tom Lynch became unwell with what doctors diagnosed as gastro. Woulfe and Leddie say Francou indicated to both the club and Collective Mind that he was satisfied with their explanations.

Another player said he was confused by a part of his process, to which it was suggested he speak directly to the lead facilitator who ran it. After failing to attend an arranged call numerous times, the player told club officials that he was all good and had moved on.

The Crows’ first match of the 2018 season, a 12-point away loss to Essendon at the Docklands Stadium, created no real concern – the Bombers are often hard to beat there. Then, three days before Adelaide’s next game – the Grand Final rematch against Richmond – a bombshell dropped.

“A cult-like pre-season camp debacle left senior Crows distressed” screamed a Fox Sports headline out of Melbourne. The article included claims that players were blindfolded for 24 hours and ended up in the middle of Australia.

Walker and Sloane immediately called a team meeting to address the allegations and the team subsequently thrashed Richmond by six goals in a blockbuster Thursday night game. But the issue never went away and new headlines appeared to pop up every week.

The reports included claims that players were tied naked to a tree; Tom Lynch was denied medical attention; the Richmond theme song was played on a continuous loop as punishment; Indigenous players were emotionally impacted; players’ families couldn’t get in touch with them; and players were encouraged to swap wives.

Leddie and Woulfe, who say each of these allegations is incorrect, watched in disbelief as the rumour and innuendo became even more persistent. Still under contract to the club, which insisted they not speak publicly, they were unable to denounce the claims or defend themselves.

The club believed a strategy of not responding publicly to the claims was the most effective way to deal with them and protect itself and the players. It was a public relations disaster.

“We felt unsafe, had no idea where the campaign was coming from, were unsure who to trust, yet felt assured by the club that they knew how to deal with this, and that they were fully supportive of our program and the relationship,” Woulfe and Leddie say.

Eventually Pyke and football manager Brett Burton, whose relationship with Woulfe provided Collective Mind’s initial connection to the Adelaide Football Club, had no option but to hold a press conference, which did little to end the speculation. Pyke tried to lighten the proceedings but the siege mentality from within the club was obvious, as it still is to this day.

Woulfe and Leddie waited until the season had finished, and their relationship with the club had been mutually concluded, before responding to persistent requests and holding their own press conference. But by this stage, they were in a no-win situation. During conversations with SAWeekend, the pair has come across as warm and charismatic. But at the press conference, in Melbourne in August 2018, neither of these attributes was able to shine as they became increasingly impatient with what they considered unfair questioning.

The allegations against Collective Mind puzzle those who are still working with the organisation. Australian Boomer and Brisbane Bullets basketball star Matty Hodgson has been mentored by Amon Woulfe for the past 18 months.

He describes the “super respectful” Woulfe as being “substance as distinct from style”. “I can’t believe the disparity between what’s been reported and the truth as I understand it,” Hodgson says.

Joey Hayes, whose Ultimate Sports Performance academy on the Gold Coast Woulfe helps to prepare athletes for elite careers, says of Woulfe: “I simply can’t fault him as a human being, the work he’s done with all our junior athletes, their parents, and our professional athletes.”

Both the AFL’s integrity unit and the Adelaide Football Club’s professional standards integrity unit launched inquiries into the camp in response to media reporting, and found no wrongdoings.

Club doctor Cesana also interviewed every player and provided a report to the AFL’s integrity unit which was, once again, satisfied. The AFL Players Association says it has received no complaints from any Crows’ players about the camp.

Since March 2018, a choking frustration has gripped both Leddie and Woulfe as a drip-feed of what they say are inaccurate and wildly speculative reports steadily emerged – mainly from Melbourne-based media outlets. To the Collective Mind principals, the Adelaide Football Club’s reluctance to defend itself (and them) adds to the frustration.

Despite this, they say the relationship with the Crows is still good. Woulfe continued to coach Walker and Sloane (paid for by the club) for the rest of the 2018 season after the formal agreement ended in June. “The relationship with the club was fine and continues to be so to this day. I still speak with people at the club and there’s ongoing friendships. There never was an issue between the club and us,” says Woulfe.

An article by Sam McClure in The Age on July 4 was the last straw. Leddie and Woulfe initiated legal action for defamation against The Age newspaper and Sam McClure, and against Channel 9 for comments made by McClure and veteran commentator Caroline Wilson.

It’s been nearly three years since the Crows came within 90 minutes of football’s grandest prize. In 2017 they were the superior team of the competition but on Grand Final day, outplayed and out-coached, they were beaten by a team that played with heart more so than head. The fall from ladder-leader to cellar-dweller has been as devastating as it has been spectacular.

In that time, speculation of what happened on the camp has been a constant distraction. “Did the camp turn into a massive distraction? Absolutely. In hindsight, would we do some things differently in relation to the camp? Probably. Was it the catastrophic, damaging, and demeaning exercise that it has been painted by some sections of the media? Definitely not,” Woulfe and Leddie say.

But to blame the club’s current state on what happened on the Gold Coast in early 2018 appears simplistic and mischievous. “It’s ludicrous to suggest that we are responsible for the Crows’ current poor form,” Woulfe and Leddie say.

Other issues the Crows have faced seem far more consequential to their current predicament than the camp. Injuries impacted significantly in 2018. Internal tensions, exposed by an external review which led to the departure of key people in the football department, undoubtedly were damaging. Perhaps more critically, failures in list management and the inability to retain key players have reduced the once-dominant playing group to one that has won just two games this season.

“We are not here to tell people what their experience of the camp should be like,” Woulfe and Leddie say. “Some loved the camp, others didn’t enjoy it, that’s OK. What’s not OK is intentionally handing over supposed ‘facts’ to the media that are blatantly incorrect, offensive, and some so wildly fabricated that it can only be assumed that the intent is to cause harm to the Crows and Collective Mind.”

Leddie and Woulfe say their business has been severely impacted and their reputations traduced. There is one bitter irony in this whole saga. Leddie and Woulfe didn’t receive one cent for their role in convening the camp. They distributed the Crows’ fee to the other facilitators.

“There wasn’t enough to go around, so we made the decision they needed to be paid,” Leddie says. “We did not get a cent from this bloody camp.”

Woulfe continues the narrative: “We did it for the love of the club, so they’d ‘never again’ have to feel that pain and loss, and all that’s come of it is we’ve continued to lose money and suffer brand damage year after year. It just keeps on giving.”

He laughs as he concludes: “We have always, and will always, stand by our work, but this is the worst investment we ever made … bloody hell.”

But there was no humour in the laugh.

Note: Adelaide Football Club provided some background information for this article but declined to go on the record.

Originally published as Adelaide Crows Camp: Collective Mind directors Amon Woulfe and Derek Leddie speak to Graham Cornes