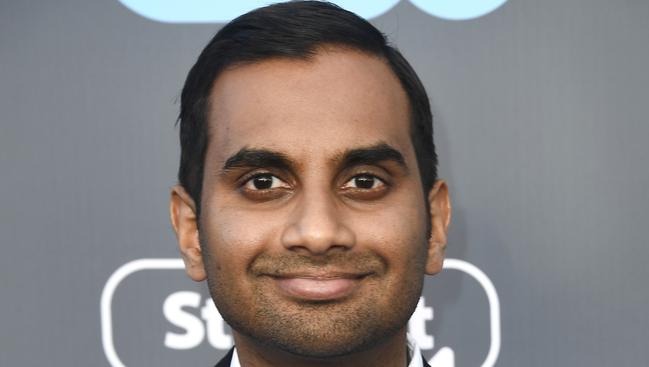

Why the Aziz Ansari story matters

THANKFULLY very few women have encountered a Harvey Weinstein. But plenty have had awful sexual experiences, and that’s why the Aziz Ansari story is significant, writes Katy Hall.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FOR better or worse, everyone has an opinion on the behaviour of Aziz Ansari right now.

Some say his encounter with a now 23-year-old woman known only as Grace was simply a case of a bad sexual experience and argue that his privacy has been terribly violated in airing the story. Others believe that the 34-year-old comedian’s actions constitute sexual assault and that the Golden Globe winner is just as bad as other Hollywood heavyweights who have recently been called out.

Irrespective of where you sit and what you think, though, there is something vitally important in this particular story being made public.

When they first came to light, the stories recounted by alleged victims of Harvey Weinstein were nothing short of harrowing. They sent shivers down the spine and, at times, made you physically recoil. And while they kicked off the #metoo movement that has since made its way around the world, there were so many elements of their experiences that simply didn’t resonate with the average man and woman.

Men like Harvey Weinstein aren’t a dime a dozen; they simply don’t have the money or the power to exist in the everyday. The menacing behaviour, threatening demeanour and power they command cannot be harnessed by your average Joe Blow. Yes, they are out there, but certainly not in great numbers.

Neither are the hotel suites in London and Hollywood; the multitude of staff at his beck and call; the promise of career-defining roles in exchange for some action. These things are all so foreign to so many.

Reading Grace’s story, though, I felt sick in a way that’s become all too familiar for many people. I’ve heard parts of this story before from friends. I’ve been Grace in parts this story myself. I know many Grace’s. And, unfortunately, I know Aziz’s too.

Men who have pulled a woman’s hand onto their crotch or kissed too eagerly or used aggressive tactics to initiate oral sex. Men who have said they respect a boundary only to try and recross it 10 minutes later and try to get you to stay even when an Uber has been ordered. Men who have been genuinely confused when a woman later confesses having been deeply uncomfortable throughout their shared experience.

In recounting their date, Grace called Ansari’s advances “aggressive” and says the events that unfolded made her feel “violated.”

Ask Ansari though, and he claims the activities of the evening were “completely consensual.”

And it’s for this reason that Grace and Ansari’s story matters so much. It is a story that so many of us know.

It is the story that has people asking what constitutes as a bad sexual experience and what constitutes sexual assault. It is the one that confirms that if a woman’s response to you saying you’ll grab a condom is “whoa, let’s relax for a sec, let’s chill,” it means she’s not ready to have sex.

It is one that drives home the point that if a woman says “I don’t want to feel forced”, she’s feeling forced. That if a woman tells you, “You guys are all the same, you guys are all the f”**king same,” that this is not a time to tongue kiss her.

It says spending five minutes in the bathroom before asking to slow things down is a woman’s way of informing you that she’s not ready to have sex without having to actually come right out and say it.

It also says that if someone is behaving like a “horny, rough, entitled 18-year-old,” try to leave sooner rather than later.

It says that in telling someone they made you feel pressured and uncomfortable, you might actually get an apology instead of the kind of abuse or aggression so many women live in fear of facing.

None of this is to say that doing any of the things Ansari — and to a broader extent James Franco — are accused of doing are okay. They’re not. But it does reiterate the glaring disconnect that currently exists between so many men and women, and our collective understanding of sexual cues and consent. Because if the stories of the past three months have shown us anything, it’s that a lot of us — particularly men — are still dancing in the dark.

If we can figure out how to bridge that gap, maybe one day we won’t be reading these stories, not because they are still being covered up, but because they no longer occur with the horrific frequency in which they currently do.

Katy Hall is a writer and producer at RendezView. @katyhallway