Suicide is not the problem of tortured artists

THE portrait of the tortured artist unable to carry on might be convenient, but it’s far from being the reality of depression and other mental illnesses, writes Katy Hall.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

EVERY time a famous person takes their own life there’s a temptation to fall back on familiar tropes.

We say that they were a tortured artist or a victim to their own brilliance. It’s implied that the trade off for their talent was dark and depressive periods, that there’s a high price to pay for being a visionary.

This is a narrative that has been applied to the deaths of Kurt Cobain, Marilyn Monroe, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Alexander McQueen, David Foster Wallace, Robin Williams, L’Wren Scott, Chris Cornell, Avicii and so many others famous artists. It’s implied that because they were artists, their suicides are somehow removed, somehow different; as though they are placed on a shelf away from everybody else’s.

It makes as much sense as the so-called “27 club”, of musicians including Cobain, Janis Joplin and Amy Winehouse, who all died at the age of 27.

“Our culture is full of assumptions and stereotypes about how the mind works, perhaps none so enduring as the legend of the “tortured artist”. The contradiction of the genius who creates great artwork despite (or because of) mental illness has been part of Western legend for thousands of years,” psychology researcher Adrienne Sussman wrote in a 2007 Standford paper.

Take, for example, the death of Soundgarden and Audioslave’s Chris Cornell, last year. In trying to make sense of what had happened, fans were quick to try and make link his illness to his artistry. One fan, journalist Chris Slater, dissected the lyrics of Cornell’s many songs and ultimately surmised, “Was Cornell the stereotypical “tortured soul” who bares his emotions onstage for the world to see? From all accounts, it looks like that was the case.”

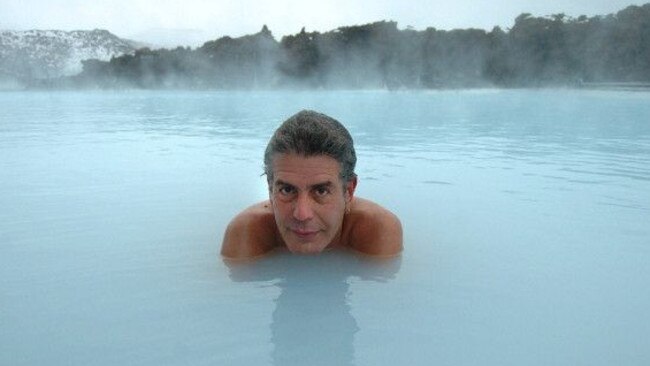

The same filter could be applied to the iconic fashion designer Kate Spade, who died at her New York home this week, aged 55, and who the New York Times described as a woman “whose handbags carried women into adulthood,” and to the inimitable chef, Anthony Bourdain, who died in Paris on Friday.

Through his tenure at Les Halles, multiple television series, and books, Bourdain offered a perspective on food that the world have never seen before, let alone embraced. He was truly a counterculture rebel of the industry that made him, and the world adored him for it.

And while it’s true that because of their fame and respective places within the global celebrity landscape that more people will mourn Spade and Bourdain’s deaths more than someone unknown outside of their immediate lives, we must remember that the mental health condition that claimed their lives is not an artistic problem or a celebrity problem or a genius problem. It is everyone’s problem and it is everywhere.

According to data published by Psychology Today in 2016, the highest suicide rates among Australians are not, as popular culture would have us believe, within the arts and humanities sectors, but in our essential services.

For a number of reasons, physicians, dentists, veterinarians, pharmacists, lawyers, farmers and police officers are among the highest groups of people likely to take or attempt to take their own lives.

These are professions that are not particularly glamorous or coveted for fame, but they do involve a high degree of risk, financial pressures, an intimate knowledge of death and successful ways to reach it, and perhaps most tragically, a belief that these positions render them unable to seek help when it is needed.

Like certain kinds of cancer and heart conditions, mental health doesn’t discriminate simply based on your artistic temperament. It’s not a parasite that latches on to only those with a Fine Arts Degree. It doesn’t recognise the hours spent in front of an easel or a keyboard or a sewing machine; it simply comes for some people and not others.

And while it’s true that art can be a form of therapy used to help people manage and recover from mental illnesses, of everything we know about mental health to help us better understand who it targets and why, the evidence that shows having an artistic temperament or being of a certain disposition makes one more or less likely to experience a condition simply doesn’t solidly exist.

But in glorifying the idea that this illness prioritises or gravitates towards some over others, we’re just proving the point that we still have much to do when it comes to breaking the taboo of mental health.

It also means we are, in part, failing to recognise the real legacies of those who have left us too soon.

If you are experiencing mental health issues or suicidal feelings contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or BeyondBlue 1300 224 636.