Juries can — and do — get it wrong

Somehow a jury found Cardinal George Pell guilty beyond reasonable doubt on the uncorroborated allegations of one victim. The lack of transparency is archaic for such a momentous decision, writes Miranda Devine.

You would think that, having lost a seemingly unlosable case, Cardinal Pell’s high-priced Melbourne barrister, Robert Richter, QC, might have chosen his words more carefully during sentencing submissions last week.

But, no. He described the oral rape of two 13-year-old choirboys for which Cardinal Pell has been convicted as “no more than a plain vanilla sexual penetration case”. It was a gobsmacking moment in a surreal week.

Richter then had to issue an apology after a “sleepless night”, as if anyone cares about his nocturnal habits.

“Terrible choice of phrase”, as he confessed, is putting it mildly. It showed contempt for victims and disregard for the catastrophe of the Catholic Church’s child sexual abuse scandals.

There is nothing “vanilla” about the charges or the enormity of the guilty verdict against the Vatican’s third-highest ranking official, the most senior Church figure found guilty of child sexual abuse. Pell’s conviction is shaking the Church to its foundations.

RELATED: Pell Lawyer Surrounded by Media on Leaving Court After ‘Plain Vanilla’ Abuse Comments

You have to wonder why Richter advised Pell that he not testify, despite Pell telling friends he wanted to. Legally, the advice made sense, especially for Richter, a criminal lawyer whose clients mostly are gangland bosses.

But to a juror, the Cardinal’s silence could made it look as if he had something to hide.

How else to explain what to any fair-minded person is a baffling verdict, once you look at the evidence, read the transcript, and watch the video of Cardinal Pell’s honest indignation while being interviewed in Rome by Victoria police.

You couldn’t say the jury weren’t aware of the high bar the prosecution had to hurdle to prove Pell orally raped two 13-year-old choir boys in St Patrick’s Cathedral after 11am Mass one Sunday in December, 1996, in a brazen attack over six minutes in a large room with an open door through which at least a dozen people had access that morning.

MORE FROM MIRANDA DEVINE: How Pell became the Vatican’s sacrificial lamb

Victorian County Court Chief Judge Peter Kidd spent the first two days of the four-week trial last November hammering the fact that the defendant is innocent until proven guilty, and that Pell was not in the dock for the sins of the Church.

But, somehow, the jury found guilt beyond reasonable doubt on the uncorroborated allegations of one victim.

All you can say is that the victim must have been very convincing when he gave evidence via videolink to a closed court, the only part of the trial that remains hidden from the public.

It came down to the victim’s word against the Cardinal’s and the jury believed him. That deserves respect.

Yet experts with no allegiance to Pell — lawyers, prosecutors, police, including a NSW child abuse squad veteran, and veteran crime reporters — have expressed surprise at the conviction in the face of such a flimsy case, particularly since the second victim never made any complaint before he died in 2014.

All week, those who can’t accept the guilty verdict have been vilified for daring to question the infallibility of the jury verdict.

It seems the only institution in our culture which remains sacrosanct is the jury system. The institution-trashers of the baby boomer Left have suddenly become the greatest defenders of the status quo, because it has brought down their bete noir.

They only prove that it’s never the principle they defend but the means to their end.

They insist that jury verdicts mustn’t be questioned. Yet Appeals Courts do just that every day.

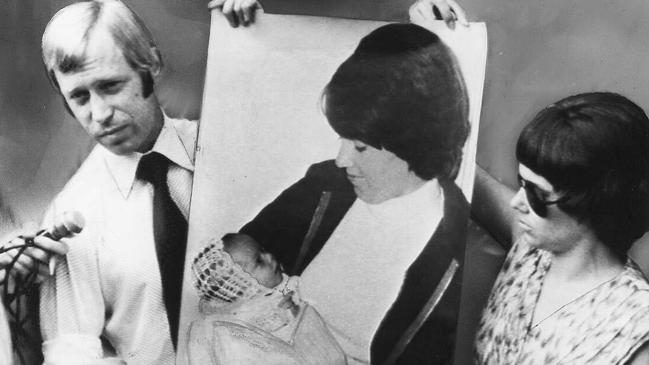

They do more than question, too. They overturn jury verdicts. The case of Lindy Chamberlain is the most famous wrongful conviction by a jury in Australia.

She spent four years in jail for the murder of her infant daughter Azaria in 1980, before her conviction was quashed.

Forensic evidence later found she was telling the truth when she said a dingo took her baby. But a jury had been convinced by prosecutors and police that she had stabbed her baby to death.

There are plenty of cases where jury verdicts have been overturned, including these high-profile ones:

— Gordon Wood spent four years in jail after being convicted of the murder of his girlfriend Caroline Byrne in 2008.

— Jeffrey Gilham spent two years in jail after being convicted of the 1993 murder of his parents and brother.

— David Eastman spent 19 years in jail after being convicted of the 1989 murder of AFP Assistant Commissioner Colin Winchester.

— Roseanne Catt spent 10 years in jail after being convicted of soliciting a person to murder her husband Barry Catt in 1989.

— Alexander McCleod-Lindsay spent nine years in jail after being convicted of the attempted murder in 1964 of his wife.

— Colin Campbell Ross was executed in 1922 after being convicted of the murder of a child. Forensic evidence led to a pardon in the 1990s, a bit late.

The point is that it’s not without precedent that juries get it wrong.

There’s little research into the accuracy of jury verdicts in Australia but a US study from Northwestern University found that as many as one in eight juries gets it wrong, either by convicting an innocent person or acquitting a guilty one.

A UK study found two thirds of jurors fail to understand the judge’s instructions.

And a study by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research found that, in only six of 25 juries surveyed, could all jurors correctly state their verdict afterwards.

Juries are not infallible.

How the Pell jurors came to their verdict is a mystery, and they are not allowed to tell us.

But in an age of transparency, it is archaic and unsettling not to know the reasons for such a momentous decision.