Foreign homebuyers desert Australia, Are we headed for a housing crisis recession when rates rise

Foreign real estate investment has sunk to its lowest level in five years, in a sign the market has become more hospitable for local buyers.

Property

Don't miss out on the headlines from Property. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The illegal ownership of Australian property by foreigners is in decline.

But the latest update from the Foreign Investment Review Board advised NSW had the highest noncompliance rate, with some 26 per cent of the cases.

After 404 residential investigations, they identified just 83 properties in breach across Australia. This was a decrease as the 2019/2020 financial year had 259 properties in breach from 620 investigations.

With just 4384 residential approvals issued in the last financial year, foreign investment sunk to its lowest level in five years. Victoria and Queensland received 58 per cent of approvals, a shift from the prior year approvals when Victoria and New South Wales dominated.

Of course the latest figures take into account the full impact of the closure of Australia’s borders after the onset of the pandemic.

Last financial year saw $10.4 billion in residential acquisitions, a marked drop from $17.1 billion in the prior financial year which was affected by the closed borders for the last few months in 2020.

The total number of residential real estate purchases in 2019/2020 had been 7056.

The last financial year unaffected by the pandemic – 2018/2019 – saw 7513 purchases totalling $14.8 billion. There had been 10,036 purchases totalling $12.5 billion in 2017/2018.

The data from the FIRB shows fewer buyers, sometimes spending more and sometimes less on their investment.

The FIRB says the decline since 2015/2016 may be explained by a tightening of domestic credit and increased restrictions on capital transfers in home countries. They also conceded Australian state taxes and foreign resident stamp duty increases may be a contributing factor.

There has certainly been a changing landscape of push and pull factors over recent years. Consecutive federal governments since Kevin Rudd, through to Malcolm Turnbull, and then Scott Morrison have sought to dampen Chinese residential investment to supposedly allow locals to have a better shot.

It was in 2010, when the Rudd government announced a hotline for the public to report suspicious buyers, amid measures to ensure foreigners did not put “pressure on housing availability for Australians”.

Liberal treasurer Joe Hockey ratcheted up the issue.

He ordered the Chinese billionaire Xu Jiayin to sell his $39 million Point Piper trophy home as it was an illegal acquisition. He also asked that one of his Hunters Hill neighbours be investigated after he became suspicious surrounding a trophy home purchase that subsequently proved compliant.

The sentiment of successive governments had been accompanied by a string of new and higher fees and taxes for foreigners.

The past few years have also seen significant policy changes in China, including tighter capital controls, such as limiting the outflow of foreign currency. The recent rise in military tensions between the two countries no doubt will dampen purchasing intent.

There was a big fine for one of the illegal owners who had spent $1.4 million on four Melbourne properties.

Justice Barry Beach imposed $250,000 penalties, well above the $162,000 that the investor argued was his net gain.

Previously illegal buyers were forced to divest but could keep all profits gained.

RECESSION FEARS OVER RISING INTEREST RATES

Should interest rates rise dramatically over the next year or so, accompanied by the forecast 15 per cent fall in property prices, I’d assume Australia will be heading for recession.

It won’t be like the recent short Covid-19 pandemic recession after the Morrison-Frydenberg government threw cash around. It will instead be punishingly problematic, like the ones in the early 1990s, the early 1980s and the mid-1970s.

And this time households have never been more indebted, notwithstanding their early repayment mortgage buffers.

While some economists were initially suggesting rate rises just couldn’t accordingly be too severe, the current market consensus is that the Reserve Bank of Australia will lift the cash rate from 0.1 per cent to somewhere between 1.25 per cent and 3 per cent.

PropTrack has calculated the possible consequences at 3 per cent. Based on the recent Sydney house median at $1.37 million and the arising $1.095m mortgage, it would see $1890 extra each month for the buyers who are currently paying $4300 in monthly repayments based on the average 2.52 per cent variable rate.

It won’t be pretty for households who will try to hang on, possibly in negative equity, but contract their spending, which will then impact businesses, employment and government revenue.

There’s been a recent policy suggestion from the United Australia Party’s Clive Palmer for a legislated 3 per cent ceiling on home lending rates for the next five years. It oughtn’t be dismissed just as bluff and bluster from a busybody billionaire.

“I can promise you I won’t lose my home,” Palmer told the National Press Club.

Palmer is reaching back to when the banking industry faced restrictions on just how they could lend to home buyers. Palmer was in his early 30s when the home loan market was tightly regulated.

For a time until the deregulation in 1986, the mortgage rate for homeowner loans of less than $100,000 was subject to a 13.5 per cent ceiling.

However the banks were curtailing lending for housing as the 13.5 per cent ceiling was lower than the 15 per cent the banks were paying in interest on bank account deposits.

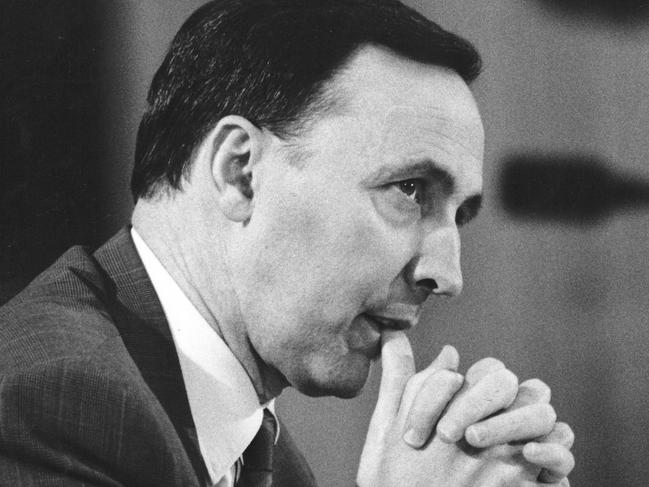

Despite opposition, the Hawke Keating government’s initial step was to remove the ceiling on new home loans, which meant that home buyers faced a 15.5 per cent rate on their average $50,000 loans – an extra $57 monthly repayment.

When the NSW premier, Neville Wran sent a telex to Bob Hawke opposing the decision, Treasurer Paul Keating privately noted “Neville can’t get his eyes off The Daily Telegraph.’’

While 1 million deregulated borrowers came to be paying record 17 per cent mortgage rates, another 800,000 remained on the regulated loans. And for a time into the early 1990s some ruthless banks held borrowers on regulated loans at 13.5 per cent even while its variable loans had dropped below.

Keating’s objective was a deregulated economy, which came with easier money, more banks and RBA independence.

One economist has suggested that Palmer’s policy had “absolutely no rational thought.” But as the housing crisis recession nears, expect more demands that seek to unscramble the Keating omelette