Danny Wallis: How the man known as the ‘serial Block bidder’ made his millions, and how his difficult journey inspired his philanthropy

From tinned fruit to Ferraris, and a bungalow to The Block – Danny Wallis’s life has been anything but predestined. He explains how his journey has encouraged his philanthropy.

Property

Don't miss out on the headlines from Property. Followed categories will be added to My News.

As a youngster, few could have imagined Danny Wallis would be destined for fame and fortune.

Today he’s the rich-lister known for splashing millions in home-buying sprees on The Block, but he grew up on hand-me-downs and the last peach slice from the tin as the youngest of seven siblings.

Like a lot of Aussie lads, he started his working life behind a lawnmower, making about $6 a day back in the 1980s – a wage he supplemented by raiding bins on rubbish night so he could flog bottles for a refund.

RELATED: The Block serial buyer outlines plan to sell all his Victorian investment homes

Danny Wallis slams Victoria, advises other investors to look interstate

The Block investigation: One in five homes lose value post-show

His technical college education should have seen him become a carpenter or a metal worker, but when his parents’ marriage broke down (when he was 16), he was left supporting himself on $25 a week from a job at Safeway.

These days he’s worth an estimated $120m and known in living rooms around the country as Danny from The Block.

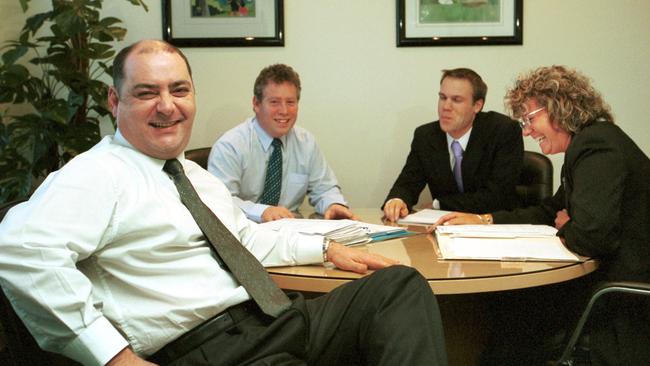

He’s been on the nation’s rich lists since 2003, and while he’s not really sure when he became famous, there was a distinct moment when his life changed course for the better.

It was a quiet day at an ANZ Bank office about 33 years ago and Wallis, by now a computer programmer, decided to write a bit of code to work out how much he would earn in salary for the rest of his life.

“It was $1m, assuming some pay rises. Wages have gone up a bit more than I thought they would, but it all looked a bit sad... I realised the only way to make money was to go bigger and employ people.

“There was a gap in the market; I could see ANZ spending fabulous amounts of money on consultants and they were getting more in a day, doing the same job I was doing – and I told them what to do.”

The IT services and consultancy business he created a year later made him, and more than a few of his employees, multi-millionaires in short order.

‘FAIRLY ROUGH’ BEGINNINGS

Surprisingly, it was his “interesting” childhood with no room for luxuries that taught him the resourcefulness and aversion to wasting money that made his firm a success.

“We had domestic violence in the house, a fairly rough upbringing … alcohol was involved,” he says.

Wallis grew up wearing hand-me-downs and eating cheap mince and chicken that his mum somehow stretched out to feed the family of nine that were squeezed into a three-bedroom Balwyn North house.

“We weren’t poor, but there were seven kids,” he says.

“We didn’t get any luxuries in life. We didn’t have real holidays, Christmas presents were not toys as such – they were school uniforms or shoes for school.

“We got one Christmas present for the whole seven kids, like a Monopoly board.

“And we’d get small desserts. A can of peaches, and by the time the can went around there was only one left in it.”

If he wanted some money to spend on himself, Wallis had to earn it – at first mowing lawns.

“I think it was $6 if I did a full day, but it might have been $2.”

He used the money to buy a bike, which helped with his side hustle – taking old bottles to the milk bar to collect the deposit.

“I could make 10 bucks in a night on rubbish bin night … and that was easier than working at lawn mowing,” Wallis says.

“Then I sold newspapers after school.”

Wallis was kicked out of home aged 16 when his parents’ marriage broke down; by this point he was earning $25 a week at Safeway – just enough for him to rent a bungalow out the back of a house in Bayswater.

“I had to go in to the house to have a shower or use the toilet,” he remembers.

“It had one power point, no airconditioning, no heating, no insulation – you’d wake up and there would be ice on things.”

A graduate of Swinburne Technical College, where most of his time was spent learning carpentry and metal work, he was an unlikely candidate to sign up for a computing traineeship at Telecom (now Telstra).

But the nine-month course led to a $15,000 a year salary, decent money in those days.

“It was a horrible course. I swore in the first week I would resign from that job within 12 months once I got the qualification. And 12 months to the day, I resigned and moved to the ANZ,” Wallis says.

He went to university part-time while working for the bank, studying for a degree in computing that saw him promoted to programmer and a $25,000-$30,000 salary.

FIRST HOME BUY

He’s become famous for his unusual multimillion-dollar bids at auction on TV, but Wallis’s first home was an $80,000 Bentleigh East address bought in about 1987, aged 24. These days a house in that suburb costs north of $1.4m.

As a bank employee he got a 60 per cent interest rate reduction – important at a time when the standard variable rate was 17 per cent.

But even then he still had to bring in a couple of housemates to help pay the mortgage.

He was still in his first home when he started his own computer consultancy and services business named DWS – his initials and “software” – in 1991.

It was never a solid title, though, and a company contest to rebrand years later threw up examples including “dorks wearing suits”. Wallis liked that one, too.

Ironically, his first client was Telecom, which brought him in to write the code behind phone cards for vending machines as part of a joint initiative between the telco and Coca-Cola Amatil to help reduce the use of cash in prisons.

Their concept ultimately failed, but Wallis’s business thrived and he was the 15th richest Australian under 40 by the time he was 39, with the press estimating his net worth at $50m-$60m in 2003.

“My accountant rang me up and said, ‘they have underestimated you’,” Wallis says.

“But suddenly I’d ring clients and I’d get meetings. That added opportunities for DWS, which opened up more doors.”

Wallis walked right through them and his personal wealth these days is at least double the 2003 young rich list estimate.

USING HIS MILLIONS TO HELP OTHERS

There was so much money. Wallis had to start finding ways to spend it.

He wasn’t the first millionaire to turn to philanthropy, but in 2004, he signed his company up for the concept of “donate a day” – which worked out to about $180,000 of revenue, and closer to $200,000 once some staff had tipped their wage in, with proceeds going to such organisations as Beyond Blue.

For most Australians, their first encounter with the IT entrepreneur was on the TV show Secret Millionaire where he surprised a struggling couple and their two terminally-ill children with a gift of tens of thousands of dollars.

It was arranged through the Butterfly Children Fund, which helps kids with epidermolysis bullosa – a rare condition that leaves them with incredibly fragile skin and in severe cases a heartbreakingly short life expectancy.

“It gave them a chance to give their two kids a bit of fun before they passed away,” he says.

“They got to take them on holidays and that, take them to things they wouldn’t have otherwise been able to do.”

In Wallis’s own childhood, there was never enough money for a getaway, so giving a struggling family the chance to take one together was a blessing.

Three years later, Wallis was at the first child’s funeral. He kept in touch with the parents for a while after, but never heard how the second child progressed.

“When you give money away, it doesn’t give you a right to enter someone’s life and hang around forever,” Wallis says. “You give without expectation.”

That was in 2009, about three years after DWS was listed on the stock exchange.

Wallis held onto 42 per cent and watched his share soar to $55m almost overnight.

DWS didn’t need money reinvested into it, so he found other places for it.

He split 10 per cent of the shares across his staff, giving each a stake in the company based on how long they had been with him.

That 10 per cent’s initial valuation came in pretty close to $13.5m.

Within three months — about 14 of his employees were millionaires or multi-millionaires as the share price surged.

There were ups and downs, but from 2006-21 his stake in the company paid $6m-$8m a year in dividends as the business continued to thrive.

Wallis chalks a decent amount of the success to three mantras around the office.

The first, “own, now, won”, was a perpetual reminder at all levels of the business that they needed to own every problem, deal with them now and that was how they made sure they always won.

His second was ABC: Assume nothing, Believe no one, and Check everything.

“Those rules would still work today,” he says.

MORE: Mum with 17 homes’ bullish prediction for Victoria

‘I ate rice for dinner a year … now I own 6 homes’

Seven deadly sins burning a hole in all our wallets

“Too often people come to answers and have got it wrong because they made an assumption and nobody checked it – they just believed what someone said.”

In 2019, Wallis was approached to sell DWS to IT firm HCL Technologies.

When the deal was finally done, the business was valued at about $250m in enterprise value.

Instead of a party, Wallis was drinking a coffee in his living room and watched via a

video feed on his computer as the courts cleared the deal.

WALLIS ENTERS THE BLOCK

Two months later, he went on The Block and bought three of that season’s homes, splashing almost $12m on the combined purchases.

A $3.8m apartment was handed over to the My Room Children’s Cancer Charity for families with sick kids to live in while they get treatment.

It’s almost the same thing he did with the first home he bought on the show back in 2012.

Wallis had just led a rescue bid for the recently collapsed company Energy Watch and then spent $1.4m buying his first property from the show wearing an Energy Watch T-shirt, in a marketing gambit borrowed from the late John Ilhan – better known as mobile phone king Crazy John.

The publicity stunt worked, just not in the way he had expected.

“All hell broke loose,” Wallis recalls.

For the next week he was in the headlines as Energy Watch employees and former staff, hoping to recoup unpaid entitlements left owing when the company went into liquidation, reacted angrily.

Wallis was at the head of a consortium that had pumped $750m into a bid to take over and save the business and as far as he was concerned, he did right by everyone involved.

But his attempt at being a white knight left his reputation black and blue for a bit.

He walked away from Energy Watch within a few weeks, but not before he contacted the Ronald McDonald House charity to offer them the home he’d bought while promoting the business.

This year might see Wallis absent from the list of Block bidders as he’s essentially ruled out buying any more Victorian homes and is actively selling off some of his vast real estate portfolio in response to the state’s overbearing land tax grab from property investors.

Whether that means he’ll still be Danny from the Block is anyone’s guess, but he’d be happier spending his money on charities than government coffers.

In addition to more high-profile spending, Wallis has set up a $22m fund from which he will donate 5 per cent to charity every year.

Diabetes research is regularly on the list of recipients. He’s got type two himself – but with careful eating he’s probably in better health these days than people half his age.

And he has a sibling with multiple myeloma, so research into blood cancer is also a common beneficiary.

As Australia’s most prolific reality TV auction buyer, Wallis has described his unusual bids, often down to the cent, as pure theatre for the cameras.

But for those who are wondering, his favourite number is four.

It appears on the licence plate of one of his favourite cars, a rare Mercedes Maybach worth the price of a house in Melbourne’s outer suburbs.

A noted revhead, he’s friends with Mark Webber, has been to 120 Grand Prix races around the world, was thrilled to watch Oscar Piastri’s efforts in Melbourne, and owns multiple high performance rides from brands ranging from Benz to Ferrari.

But cars – even his first, a long-lost Datsun 1600 bought for $1100 when was 17 – fall a long way short of his greatest love so far.

Herby, a schnoodle (schnauzer crossed with a poodle), was the last one left from his litter when Wallis turned up.

But every dog has its day and the charmed canine went to his forever home in style. “I picked him up in a helicopter … then I put him in a Ferrari once the helicopter landed.

“And he’s had a very good life since.”

A few friends have since confided to Wallis they thought he would have taken Herby to the pound in a matter of weeks, but years later the pooch still follows him everywhere.

“He used to be in the office with me, and they loved him (there). He’s the best dog.”

While he’s sold the business that started it all, Wallis says he still has many investments – from a farm in Deniliquin to commercial properties in Queensland and across NSW.

He is no longer a regular in the office.

These days the decision to head into the city, Herby in tow, or for the pair to stay put in his bayside home is usually made while he assesses the weather from his bedroom window.

It looks out over Port Phillip Bay from what Wallis is convinced is the “best house in the street”.

“I’ll be in this one for 50 years.”

He could easily afford to live in Australia’s wealthiest enclaves, such as Bellevue Hill in Sydney or Teneriffe in Brisbane.

But the Victorian has no interest in Melbourne’s priciest patch.

“I hate Toorak, everywhere you go there’s traffic jams,” he says.

Even so, his bayside residence is far from the typical bachelor pad.

It had been slated to become a five-apartment complex before the developer ran into the 2008 global financial crisis and had to sell.

Wallis saw it while driving past one day, well away from his normal route home to a neighbouring suburb, and decided the waterfront address was perfect.

Designed in conjunction with BBP architect David Balestra-Pimpini, the four-bedroom, seven-bathroom home spans four levels.

A basement where his car collection usually resides passes for a ballroom when it’s decked out for an event, complete with a turntable doubling as a rotating dancefloor.

His basement has even hosted former prime minister Tony Abbott for a function, while he was in the nation’s top job.

It’s rounded out with a wine cellar and a cinema with an adjoining kitchen “for snacks when I’m entertaining in there”.

The ground level has a self-contained “butler’s apartment” and if he’s running business meetings at home there’s spaces for that available – as well as a kitchen if the meeting needs catering.

The first floor is another entertainment hub, with a kitchen for show and a commercial kitchen tucked away for caterers when he’s hosting events on that level.

There’s another kitchen attached to the main bedroom, mostly for making a coffee. Wallis is pretty sure he hasn’t used the dishwasher in that one yet.

But his favourite part is the staircase made from two steel sheets with stairs that lead down to a water feature at its base. It was his idea – and generates a lot of comments from visitors, he says.

What Danny Wallis calls home these days is a long way removed from the crowded Balwyn North three-bedder he grew up in.

The kid who grew up hoping for the last peach slice in the tin has come a long way.

Sign up to the Herald Sun Weekly Real Estate Update. Click here to get the latest Victorian property market news delivered direct to your inbox.

MORE: REBAA slams ‘unethical’ homebuyer’s advocates for money grabbing

Melbourne man makes decade-long Monopoly play on one street

Australian home prices: Homeowners due to get loan relief by December

Originally published as Danny Wallis: How the man known as the ‘serial Block bidder’ made his millions, and how his difficult journey inspired his philanthropy