The Sydney north shore and eastern suburb professionals on frontline against silent killer cancer

Only 48 per cent of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer will survive beyond five years. But scientific breakthroughs are giving new hope. See how.

Wentworth Courier

Don't miss out on the headlines from Wentworth Courier. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Today, four women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Sadly, three will die.

It’s the most insidious and lethal of all gynaecological diseases and only 48 per cent of women diagnosed will survive beyond five years.

It has the lowest survival rate of any women’s cancer. It is often diagnosed late because the symptoms are vague and resemble those of many other conditions.

Bloating, nausea, indigestion, a change in bowel habits, frequent urination and excessive tiredness can all be signs, but unfortunately many doctors don’t think to check for ovarian cancer.

It is vital that women become aware of these symptoms, listen to their bodies and ask the right questions.

The key to surviving ovarian cancer lies in better detection. If found early, many ovarian cancer patients can be cured.

Whereas great advances have been made in relation to breast and cervical cancers, thanks to mammograms and the cervical vaccine, there is no early detection test for ovarian cancer.

UNDER THE RADAR

According to the Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation, it’s a disease that has flown under the radar for far too long and suffered from a lack of funding.

Because it is incredibly difficult to detect, most women will be diagnosed at stage 3 or 4, where the survival rate is 29 per cent.

Ovarian cancer is the growth of malignant cells in one or both ovaries. It’s a complex disease – there are 30 subtypes which act differently. There can be a genetic component, but often the causes are unknown.

It is most often treated with a combination of surgery and chemotherapy.

One of the obstacles to improving outcomes is that this cancer is treated as a single disease as opposed to a complex disease that requires multiple, distinct treatments.

But researchers are increasingly moving towards a personalised treatment for ovarian cancer and, thanks to their dedication, the survival rates in Australia are among the highest in the world.

Professor Susan Ramus from UNSW is an international expert in ovarian cancer research, with a focus on genetics and genomics.

She co-leads the Ovarian Tumour Tissue Analysis consortium and is developing a range of tumour tests for ovarian cancer.

She wants to improve ovarian cancer outcomes with early detection through genetic risk prediction and by developing personalised treatments using tumour profiling.

“We want to identify women at risk of ovarian cancer before they develop the disease so they can take preventive measures. For example, Angelina Jolie had preventive surgery to prevent both breast and ovarian cancer,” Ramus says.

“With tumour profiling, we look at the DNA from the tumours, trying to generate a signature which will predict at diagnosis which patients may respond well to treatments and those who won’t.

“The majority of women receive the same treatment. We want to develop tumour tests to determine the best personalised treatment.

“An early screening test is the holy grail of what we hope to achieve. There is a range of opinions as to when this will be available. At the moment, the only way to pick up people before they have the cancer is through genetic testing. With the genetic work there can be more personalised risk prediction.

“Awareness is key. Because the symptoms are non-specific, you have to trust your doctor is testing for the right things and follow up on your issues.”

IT’S PERSONAL

This ambiguity in the symptoms is something that Siobhan O’Sullivan, a 48-year-old patient from Annandale, has experienced first-hand.

“I was diagnosed two and a half years ago, and was stage 3,” she says. “I felt unwell for about two weeks before diagnosis. My midsection was bloated and heavy, but I thought I had just put on a little weight.

“The first GP I saw misdiagnosed me. She said that it was most likely constipation. She told me to go home and take laxatives.

“I returned to the practice three days later and saw a different doctor, who sent me for a blood test. A few hours later he phoned to tell me that something was seriously wrong and to go straight to Emergency. It was there I was told I had ovarian cancer.

“I had the standard treatment at first: four rounds of chemo, followed by the cancer removal surgery, then two more rounds of chemo. But as soon as my primary treatment was complete, the cancer had already spread. I am classified as ‘chemo resistant’.

“I then joined a drug trial but was removed from the trial when the cancer spread again.

“I have also had 15 rounds of radiotherapy, which is rarely used for ovarian cancer.

“I am hoping that another drug trial will come along. That is where hope lies.

“I am now terminal. I am in outpatient palliative care.

“If you have any of the symptoms of ovarian cancer, no matter how mild, you should go to your GP immediately.

“Because ovarian cancer is rare, it is likely your GP will not have come across it before. You need to advocate for yourself and ask for a blood test. The test is called ‘CA125’.”

BREAKING THROUGH

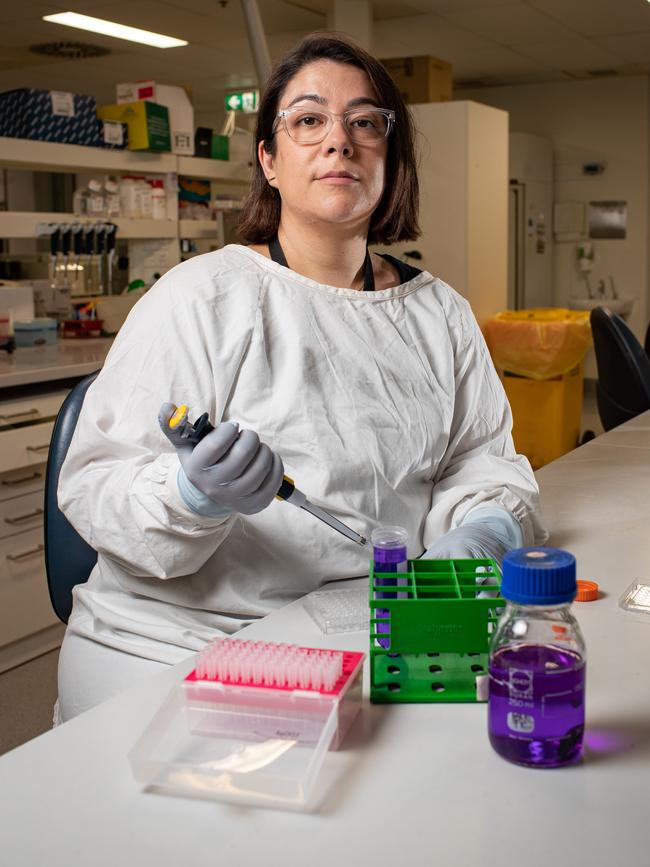

At the Kolling Institute of Medical Research, researchers have identified new genes involved in the spread of ovarian cancer.

They are focusing on the role of the tumour microenvironment, which provides the support network the tumour cells need to survive and spread through the body.

Lead author Dr Emily Colvin has been investigating the role of a specific cell in the ovarian tumour microenvironment called a cancer-associated fibroblast.

“We have identified new genes that are switched on in these fibroblasts and influence ovarian tumour spread. These genes may play a role in how tumours avoid destruction by the immune system,” Colvin says.

“Knowledge of the genes involved in the initiation of ovarian cancer is pivotal to developing effective treatments.

“The microenvironment plays a huge role in how a patient will respond to therapy or develop resistance to drugs, or whether or not the cancer will metastasise, yet it has been largely ignored in ovarian cancer research.

“By understanding how cancer cells communicate with their microenvironment, we will be able to better target them.

“We are really interested in trying to discover why the microenvironment in ovarian cancer is a little bit different to other cancers and why it’s a little bit more resistant to immunotherapy.

“We are also keen to get started with liquid biopsy research. It’s radically replacing the need for tissue biopsy with blood tests that can tell us about a patient’s tumour. This has the potential to really change the way we treat all cancers, but particularly ovarian tumours.

“Better research funding and high-profile advocacy can really change patient outcomes – we’ve seen that with breast cancer. We just don’t get that type of funding for gynaecological cancers.

“Within the next decade, we would love to see an early diagnostic test.”

Colvin’s research is receiving international attention, following publication in the journal Cancer Science.

Professor Anna DeFazio from the University of Sydney is the chief investigator on the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study.

Her research team aims to match ovarian cancer patients with the treatment or clinical trial most likely to work for their type of cancer.

AWARENESS IS KEY

The INOVATe program (Individualised Ovarian Cancer Treatment through Integration of Genomic Pathology into Multidisciplinary Care) aims to better understand the many types of ovarian cancer, each with unique genetic and molecular characteristics, eventually leading to personalised treatments.

One of the ways of achieving this is through analysing donated tumours and Olivia Curtis, a 38-year-old patient from the Central Coast, was more than happy to offer hers to the INOVATe study.

“I was first diagnosed in 2020,” she says. “I have a rare, low-grade serous ovarian cancer.

“My symptoms were vague and diffuse and came on over a period of 12 months. I had a lot of pain during intercourse, I was bloated, I was also having issues eating and found myself absolutely exhausted in the evening. By the time I went to the GP, I could actually feel a mass.

“Why did I leave it for 12 months? I was a working mum. I also had an IUD and thought my symptoms could be related to that. I assumed the mass I was feeling was a fibroid. I was rationalising everything.

“I knew nothing of ovarian cancer and its symptoms. I had my Gardasil injection when I was 12 and felt protected. Many of us think like that because we group all reproductive cancers together.

“I was in shock when my gynaecologist told me I had ovarian cancer. I had six rounds of chemotherapy and my cancer markers returned to normal and I achieved NED (no evidence of disease) for about 12 months. The cancer is now back and is resistant to chemo. I am currently taking part in a drug trial.

“This cancer is a war of attrition. It’s a war of attrition I am slowly winning because I am still here.

“The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund does great work in raising awareness and funds, but when you think of the money that has been put into breast cancer and how far they have been able to come with their survival rates, it’s time more funding was put into ovarian cancer.

“It’s my job to advocate for me and for everybody with ovaries. What inspires me is knowing that I am one of the lucky ones. I feel an immense sense of responsibility to do what I can to spread the word.”

The correlation between advocacy, funding and patient outcomes is tragic, when you think about it.

Cancer is, at best, a random act of misery that can affect anyone at any time. And yet, we give preference to the pink ribbon and the moustache because of good marketing campaigns.

It’s time we make ovarian cancer part of the conversation. Raise awareness and give it better funding, so that tomorrow, when four women are diagnosed, three of them won’t have to die.

February is Ovarian Cancer Awareness Month in Australia. World Ovarian Cancer Day is on May 8.