Police re-enact the heroic rescue of James Johnson from the Dunbar wreck at Watsons Bay

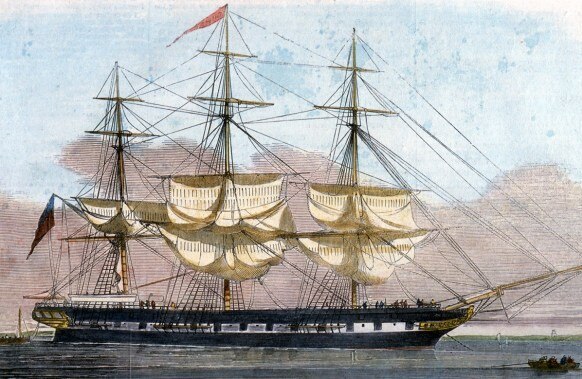

ON THE 161st anniversary of the wreck of the Dunbar we look back at the Watsons Bay tragedy. David Wood gives his interpretation of the disaster where 20 per cent of Sydney’s population flocked to the site of mass death, and where people fought with sharks over bodies, and which spawned a rock song.

Wentworth Courier

Don't miss out on the headlines from Wentworth Courier. Followed categories will be added to My News.

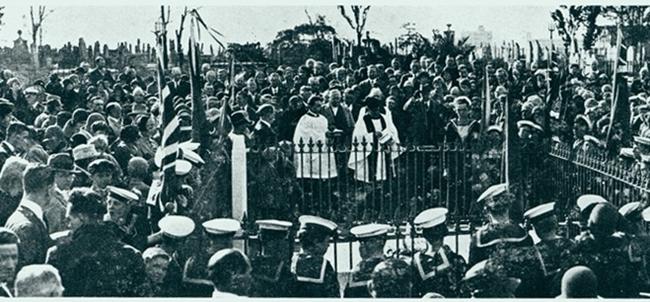

NSW Police re-enacted the rescue of James Johnson on the 161st anniversary of the wreck of the Dunbar this week at a commemoration attended by, among others, Johnson’s relative, James Hanson and film director, Watson’s Bay local George Miller.

The Minister for Heritage Gabrielle Upton called it one of the saddest stories for its sheer scale and announced more research into the wreck site.

A minute silence was held on the cliffs above Dunbar Head to commemorate the greatest peacetime shipwreck disaster in the state’s history.

“We will be undertaking the first side-scan sonar survey of the wreck, which lies some 11 metres underwater, to map the site and this will add to our understanding of its archaeological extent,” Ms Upton said.

THE RE-ENACTMENT — AS INTERPRETED BY DAVID WOOD

THE wreck of the Dunbar killed all, up to 136 people on board the night of August 20, bar a tinny bastard named James Johnson.

Johnson was washed by wave onto a ledge, sitting there for 36 hours, before he was rescued by Antonia Wollier. (Today he might have been sitting in withdrawal from his smart phone, a loss greater than being stuck on the ledge).

Johnson went on to be the lighthouse keeper at Newcastle and was involved in rescuing the sole survivor of the sinking of the SS Cwaarra in 1866.

DIVING THE DUNBAR WRECK

On Monday the NSW Police Rescue and Bomb Disposal Unit — the bomb squad I expect because a presumption all boat people are terrorists — did a rescue re-enactment with commemoration.

But the wreck maybe was best commemorated by the band Point Blank Australia with the song, Wreck of the Dunbar, possibly the only rock song inspired by a ship wreck, and off the album Getting off at Redfern from 2009, which also contained the tracks, Does the Carpet Match the Curtains? an, Attack of the Toxic Shock Tampons and the surely a classic, So I Married a F**ktard Murderer.

“Big thing going down, but we’re not ready,” goes the second verse and the only part of the song that seems anywhere near on topic.

“Our ship is comin’ ‘round, and sailing steady.

“We’re crashing into the rocks, down and sinking.

“They’re still tied to the dock, we’ll never make it.

To say it seems tenuous is as big an understatement as saying a few people died on the Dunbar.

Back in 1857, in the antipodal of the ghoul of the days before, about 20,000 people lined George St for the funeral procession. Malcolm Young got nowhere near that.

There were 22 bodies recovered, the rest made the sharks playful.

And on that, they were very playful.

“Human bodies and the carcasses of bulls were located floating as far as The Spirt (sic) in Middle Harbour,” one account said.

“Mr P Cohen, of Manly Beach Hotel, saw two bodies floating and tried to recover them, but in consequence of the number of sharks, and the ferocity with which they fought for

their prey, he was unable to do so,” a media report of August 22, 1857, said.

It was reproduced in Keiran Hosty’s article, The Melancholy Wreck of the Dunbar.

But perhaps ghoul and mass public, now Facebook grief are not that far apart really. One is just more honest about what it wants.

About 20 per cent of Sydney’s population thronged to The Gap to watch the dead being dashed against rocks.

It was before Facebook Live, to be fair, so you couldn’t savour mass death as vicariously. That was 10,000 people, according to media reports on August 22, 1857 reproduced in the book Dunbar 1857 Disaster on our Doorstep, also Hosty — incidentally Melbourne had a population of about 400,000 at the time.

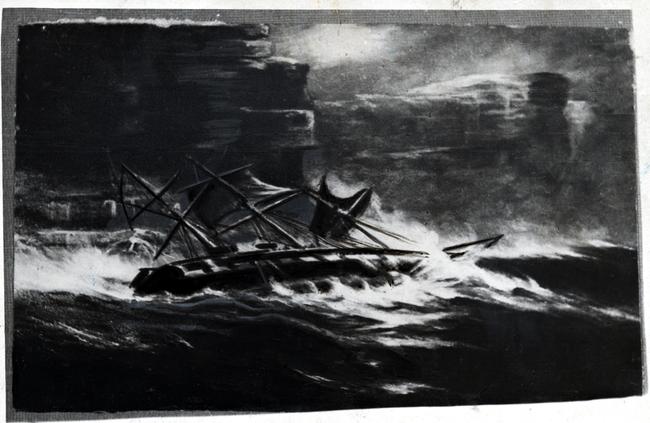

“At length it generally becomes known in Sydney that numerous dead and mutilated bodies of men, women and children were seen floating in the ‘Gap’ thrown by immense waves at a great height; and dashed pitilessly against the rugged cliffs, the returning water sweeping them from the agonised sight of the horrified spectators …” James Fryer wrote in the A Narrative of the Melancholy Wreck of the “Dunbar”, and reproduced in Hosty’s book.

“ … The scene is described by parties present to have exercised some sort of hideous fascination, that seemed to bind them to the spot … each determination to leave the fatal locality, became overpowered by a desire for further knowledge, many dreading lest they should have to recognise the familiar face of a friend or relative.”

WRECK OF THE DUNBAR BY POINT BLANK

In George Bradshaw’s Narrative of the Wreck of the Dunbar from 1857, he also discusses the draw of the mass casualties on Sydney’s population.

“By three o’clock some hundreds of {horse drawn} cabs from Sydney, as well as several omnibuses, loaded to excess, had bought people to view the heart-rendering scene of destruction going on in the Gap,” he wrote.

“Dead bodies by dozens were every minute being dashed upon rocks by each wave, mountainous in themselves.

“Presently bodies without hands, legs, arms, bale goods, bedding, beams, ship’s knew, and every imaginable article were being hurled in the air, some 60 or 70 feet by the violence of the waves.”

On the cover is his book — which took the full name, A Narrative of the Melancholy Wreck of the “Dunbar,” Merchant Ship, of the South head of Port Jackson, August 20th, 1857, with Illustrations of the Principal Localities, Fryer — because he obviously thought the title didn’t take up enough space, he broke into poetry.

Warning no heard or seen — no help at hand —

The wide bosom of the angry deep

With irresistible and cruel forces

Receive them all. One only cast alive.

Fainting and breathless on the fatal rocks —

To weeping friends and strangers afterwards

Thus told this melancholy tale.

The story of the wreck also made it to celluloid. In 1912, The Wreck of the Dunbar or The Yeoman’s Wedding silent film was staring a woman who hopefully was true to her name, Louise Lovely (who married a gay man and had four sexless first years or married a womaniser — depending if you believe Wikipedia or The Truth newspaper- but got divorced and remarried in the same day so apparently got over it).

She was also Australia’s first Hollywood star.

But the movie is considered lost, like the Dunbar; not known to be held in any collections.